When we think of gravity, we typically think of it as a force between masses. When you step on a scale, for example, the number on the scale represents the pull of the Earth’s gravity on your mass, giving you weight. It is easy to imagine the gravitational force of the Sun holding the planets in their orbits, or the gravitational pull of a black hole. Forces are easy to understand as pushes and pulls.

But we now understand that gravity as a force is only part of a more complex phenomenon described the theory of general relativity. While general relativity is an elegant theory, it’s a radical departure from the idea of gravity as a force. As Carl Sagan once said, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” and Einstein’s theory is a very extraordinary claim. But it turns out there are several extraordinary experiments that confirm the curvature of space and time.

The key to general relativity lies in the fact that everything in a gravitational field falls at the same rate. Stand on the Moon and drop a hammer and a feather, and they will hit the surface at the same time. The same is true for any object regardless of its mass or physical makeup, and this is known as the equivalence principle.

Since everything falls in the same way regardless of its mass, it means that without some external point of reference, a free-floating observer far from gravitational sources and a free-falling observer in the gravitational field of a massive body each have the same experience. For example, astronauts in the space station look as if they are floating without gravity. Actually, the gravitational pull of the Earth on the space station is nearly as strong as it is at the surface. The difference is that the space station (and everything in it) is falling. The space station is in orbit, which means it is literally falling around the Earth.

This equivalence between floating and falling is what Einstein used to develop his theory. In general relativity, gravity is not a force between masses. Instead gravity is an effect of the warping of space and time in the presence of mass. Without a force acting upon it, an object will move in a straight line. If you draw a line on a sheet of paper, and then twist or bend the paper, the line will no longer appear straight. In the same way, the straight path of an object is bent when space and time is bent. This explains why all objects fall at the same rate. The gravity warps spacetime in a particular way, so the straight paths of all objects are bent in the same way near the Earth.

So what kind of experiment could possibly prove that gravity is warped spacetime? One stems from the fact that light can be deflected by a nearby mass. It is often argued that since light has no mass, it shouldn’t be deflected by the gravitational force of a body. This isn’t quite correct. Since light has energy, and by special relativity mass and energy are equivalent, Newton’s gravitational theory predicts that light would be deflected slightly by a nearby mass. The difference is that general relativity predicts it will be deflected twice as much.

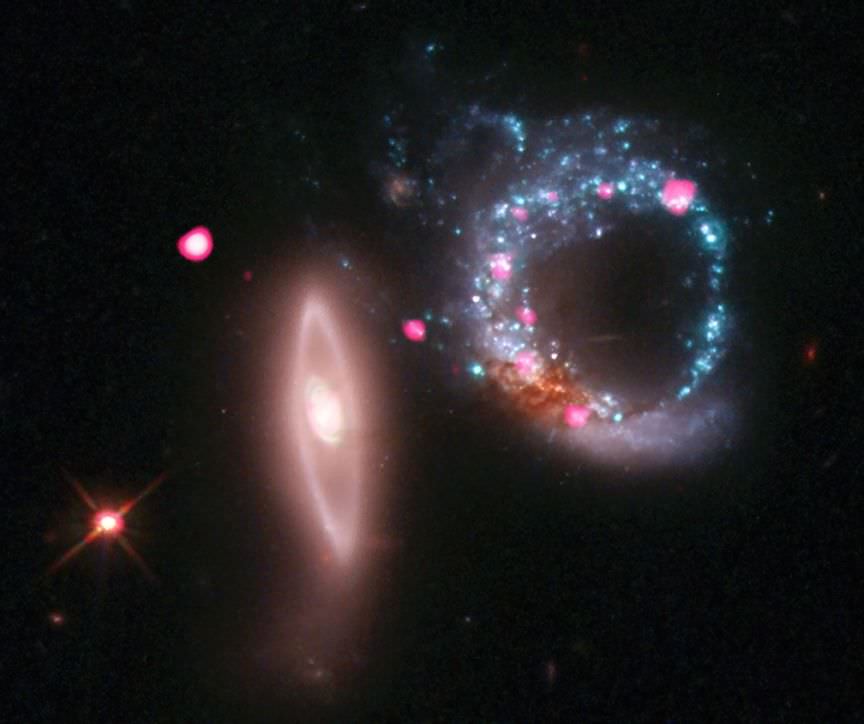

The effect was first observed by Arthur Eddington in 1919. Eddington traveled to the island of Principe off the coast of West Africa to photograph a total eclipse. He had taken photos of the same region of the sky sometime earlier. By comparing the eclipse photos and the earlier photos of the same sky, Eddington was able to show the apparent position of stars shifted when the Sun was near. The amount of deflection agreed with Einstein, and not Newton. Since then we’ve seen a similar effect where the light of distant quasars and galaxies are deflected by closer masses. It is often referred to as gravitational lensing, and it has been used to measure the masses of galaxies, and even see the effects of dark matter.

Another piece of evidence is known as the time-delay experiment. The mass of the Sun warps space near it, therefore light passing near the Sun is doesn’t travel in a perfectly straight line. Instead it travels along a slightly curved path that is a bit longer. This means light from a planet on the other side of the solar system from Earth reaches us a tiny bit later than we would otherwise expect. The first measurement of this time delay was in the late 1960s by Irwin Shapiro. Radio signals were bounced off Venus from Earth when the two planets were almost on opposite sides of the sun. The measured delay of the signals’ round trip was about 200 microseconds, just as predicted by general relativity. This effect is now known as the Shapiro time delay, and it means the average speed of light (as determined by the travel time) is slightly slower than the (always constant) instantaneous speed of light.

A third effect is gravitational waves. If stars warp space around them, then the motion of stars in a binary system should create ripples in spacetime, similar to the way swirling your finger in water can create ripples on the water’s surface. As the gravity waves radiate away from the stars, they take away some of the energy from the binary system. This means that the two stars gradually move closer together, an effect known as inspiralling. As the two stars inspiral, their orbital period gets shorter because their orbits are getting smaller.

For regular binary stars this effect is so small that we can’t observe it. However in 1974 two astronomers (Hulse and Taylor) discovered an interesting pulsar. Pulsars are rapidly rotating neutron stars that happen to radiate radio pulses in our direction. The pulse rate of pulsars are typically very, very regular. Hulse and Taylor noticed that this particular pulsar’s rate would speed up slightly then slow down slightly at a regular rate. They showed that this variation was due to the motion of the pulsar as it orbited a star. They were able to determine the orbital motion of the pulsar very precisely, calculating its orbital period to within a fraction of a second. As they observed their pulsar over the years, they noticed its orbital period was gradually getting shorter. The pulsar is inspiralling due to the radiation of gravity waves, just as predicted.

Finally there is an effect known as frame dragging. We have seen this effect near Earth itself. Because the Earth is rotating, it not only curves spacetime by its mass, it twists spacetime around it due to its rotation. This twisting of spacetime is known as frame dragging. The effect is not very big near the Earth, but it can be measured through the Lense-Thirring effect. Basically you put a spherical gyroscope in orbit, and see if its axis of rotation changes. If there is no frame dragging, then the orientation of the gyroscope shouldn’t change. If there is frame dragging, then the spiral twist of space and time will cause the gyroscope to precess, and its orientation will slowly change over time.

We’ve actually done this experiment with a satellite known as Gravity Probe B, and you can see the results in the figure here. As you can see, they agree very well.

Each of these experiments show that gravity is not simply a force between masses. Gravity is instead an effect of space and time. Gravity is built into the very shape of the universe.

Think on that the next time you step onto a scale.