One of the benefits of being an astrophysicist is your weekly email from someone who claims to have “proven Einstein wrong”. These either contain no mathematical equations and use phrases such as “it is obvious that..”, or they are page after page of complex equations with dozens of scientific terms used in non-traditional ways. They all get deleted pretty quickly, not because astrophysicists are too indoctrinated in established theories, but because none of them acknowledge how theories get replaced.

For example, in the late 1700s there was a theory of heat known as caloric. The basic idea of caloric was that it was a fluid that existed within materials. This fluid was self-repellant, meaning it would try to spread out as evenly as possible. We couldn’t observe this fluid directly, but the more caloric a material has the greater its temperature.

From this theory you get several predictions that actually work. Since you can’t create or destroy caloric, heat (energy) is conserved. If you put a cold object next to a hot object, the caloric in the hot object will spread out to the cold object until they reach the same temperature. When air expands, the caloric is spread out more thinly, thus the temperature drops. When air is compressed there is more caloric per volume, and the temperature rises.

We now know there is no “heat fluid” known as caloric. Heat is a property of the motion (kinetic energy) of atoms or molecules in a material. So in physics we’ve dropped the caloric model in terms of kinetic theory. You could say we now know that the caloric model is completely wrong.

Except it isn’t. At least no more wrong than it ever was.

The basic assumption of a “heat fluid” doesn’t match reality, but the model makes predictions that are correct. In fact the caloric model works as well today as it did in the late 1700s. We don’t use it anymore because we have newer models that work better. Kinetic theory makes all the predictions caloric does and more. Kinetic theory even explains how the thermal energy of a material can be approximated as a fluid.

This is a key aspect of scientific theories. If you want to replace a robust scientific theory with a new one, the new theory must be able to do more than the old one. When you replace the old theory you now understand the limits of that theory and how to move beyond it.

In some cases even when an old theory is supplanted we continue to use it. Such an example can be seen in Newton’s law of gravity. When Newton proposed his theory of universal gravity in the 1600s, he described gravity as a force of attraction between all masses. This allowed for the correct prediction of the motion of the planets, the discovery of Neptune, the basic relation between a star’s mass and its temperature, and on and on. Newtonian gravity was and is a robust scientific theory.

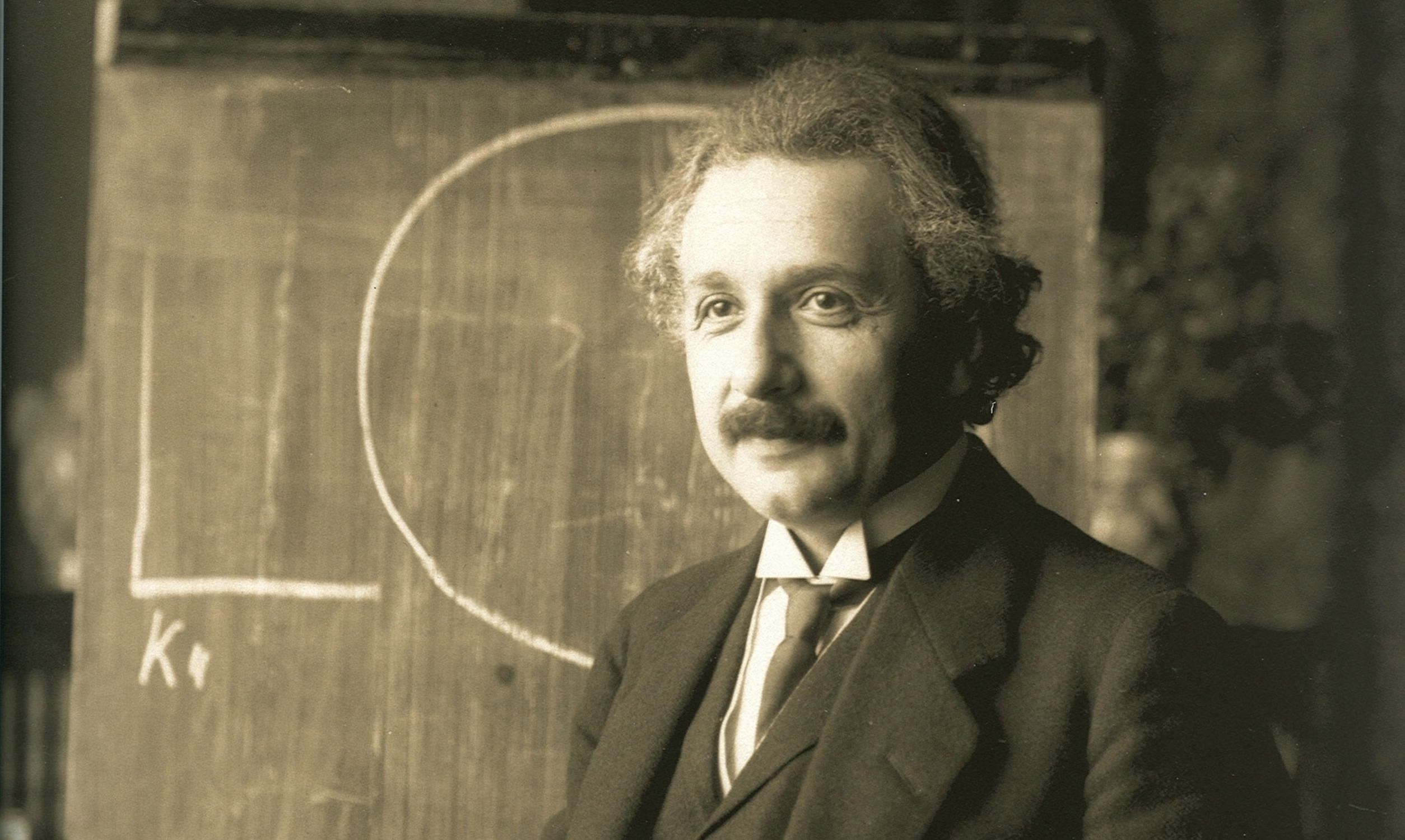

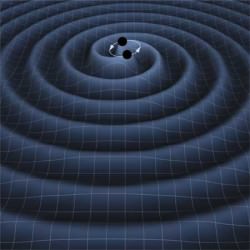

Then in the early 1900s Einstein proposed a different model known as general relativity. The basic premise of this theory is that gravity is due to the curvature of space and time by masses. Even though Einstein’s gravity model is radically different from Newton’s, the mathematics of the theory shows that Newton’s equations are approximate solutions to Einstein’s equations. Everything Newton’s gravity predicts, Einstein’s does as well. But Einstein also allows us to correctly model black holes, the big bang, the precession of Mercury’s orbit, time dilation, and more, all of which have been experimentally validated.

So Einstein trumps Newton. But Einstein’s theory is much more difficult to work with than Newton’s, so often we just use Newton’s equations to calculate things. For example, the motion of satellites, or exoplanets. If we don’t need the precision of Einstein’s theory, we simply use Newton to get an answer that is “good enough.” We may have proven Newton’s theory “wrong”, but the theory is still as useful and accurate as it ever was.

Unfortunately, many budding Einsteins don’t understand this.

To begin with, Einstein’s gravity will never be proven wrong by a theory. It will be proven wrong by experimental evidence showing that the predictions of general relativity don’t work. Einstein’s theory didn’t supplant Newton’s until we had experimental evidence that agreed with Einstein and didn’t agree with Newton. So unless you have experimental evidence that clearly contradicts general relativity, claims of “disproving Einstein” will fall on deaf ears.

The other way to trump Einstein would be to develop a theory that clearly shows how Einstein’s theory is an approximation of your new theory, or how the experimental tests general relativity has passed are also passed by your theory. Ideally, your new theory will also make new predictions that can be tested in a reasonable way. If you can do that, and can present your ideas clearly, you will be listened to. String theory and entropic gravity are examples of models that try to do just that.

But even if someone succeeds in creating a theory better than Einstein’s (and someone almost certainly will), Einstein’s theory will still be as valid as it ever was. Einstein won’t have been proven wrong, we’ll simply understand the limits of his theory.