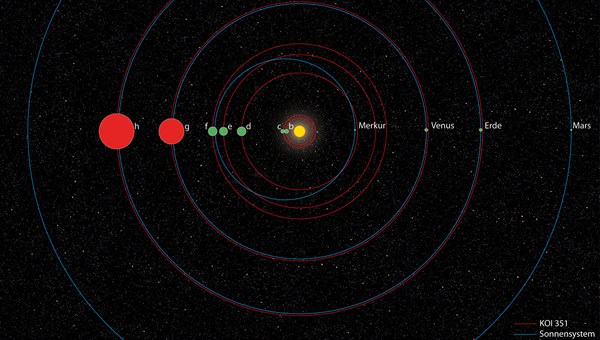

A team of European astronomers has discovered a second planetary system, the closest parallel to our own solar system yet found. It includes seven exoplanets orbiting a star with the small rocky planets close to their host star and the gas giant planets further away. The system was hidden within the wealth of data from the Kepler Space Telescope.

KOI-351 is “the first system with a significant number of planets (not just two or three, where random fluctuations can play a role) that shows a clear hierarchy like the solar system — with small, probably rocky, planets in the interior and gas giants in the (exterior),” Dr. Juan Cabrera, of the Institute of Planetary Research at the German Aerospace Center, told Universe Today.

Three of the seven planets orbiting KOI-351 were detected earlier this year, and have periods of 59, 210 and 331 days — similar to the periods of Mercury, Venus and Earth.

But the orbital periods of these planets vary by as much as 25.7 hours. This is the highest variation detected in an exoplanet’s orbital period so far, hinting that there are more planets than meets the eye.

In closely packed systems, the gravitational pull of nearby planets can cause the acceleration or deceleration of a planet along its orbit. These “tugs” cause the variations in orbital periods.

They also provide indirect evidence of further planets. Using advanced computer algorithms, Cabrera and his team detected four new planets orbiting KOI-351.

But these planets are much closer to their host star than Mercury is to our Sun, with orbital periods of 7, 9, 92 and 125 days. The system is extremely compact — with the outermost planet having an orbital period less than the Earth’s. Yes, the entire system orbits within 1 AU.

While astronomers have discovered over 1000 exoplanets, this is the first solar system analogue detected to date. Not only are there seven planets, but they display the same architecture — rocky small planets orbiting close to the sun and gas giants orbiting further away — as our own solar system.

Most exoplanets are strikingly different from the planets in our own solar system. “We find planets in any order, at any distance, of any size; even planetary classes that don’t exist in the solar system,” Cabrera said.

Several theories including planet migration and planet-planet scattering have been proposed to explain these differences. But the fact of the matter is planet formation is still poorly understood.

“We don’t know yet why this system formed this way, but we have the feeling that this is a key system in understanding planetary formation in general and the formation of the solar system in particular,” Cabrera told Universe Today.

The team is extremely hopeful that the upcoming mission PLATO will receive funding. If so, it will allow them to take a second look at this system — determining the radius and mass of each planet and even analyzing their compositions.

Follow-up observations will not only allow astronomers to determine how this planetary system formed, it will provide hints as to how our own solar system formed.

The paper has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal and is available for download here.