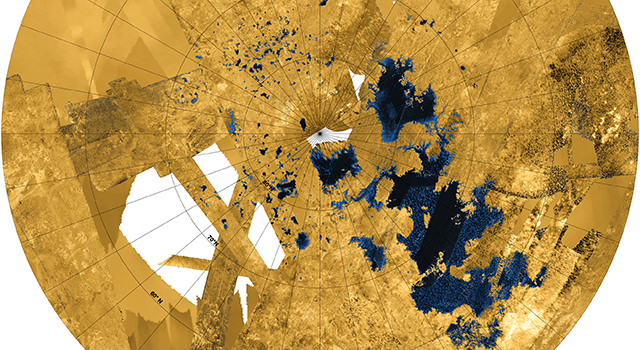

Saturn’s moon Titan has the only known liquid lakes beyond planet Earth, and new data from the Cassini spacecraft’s radar instrument provides an intriguing 3-D flyover of these hydrocarbon lakes and seas at the north pole region. Steve Wall, Cassini acting radar team lead, provided a guided tour as he presented the video at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco, noting that the vertical heights are exaggerated tenfold and the data has been colorized, both for visual effect.

The video starts by zooming into the southern end of Kraken Mare, the largest of Titan’s seas, and as you fly a little farther, Wall said the things that look like little islands are just noise in the radar data. Next, comes Ligea Mare, with its rugged coastline, and you’ll see that the liquid flow into the surrounding terrain, which appear like river valleys.

The “smooth” area that stretches farther from Ligea Mare is actualy not so smooth, but is just an area when the science team doesn’t have topographical data yet.

The video then continues to other smaller lakes that are nestled into valleys and rugged terrain.

“Learning about surface features like lakes and seas helps us to understand how Titan’s liquids, solids and gases interact to make it so Earth-like,” said Wall. “While these two worlds aren’t exactly the same, it shows us more and more Earth-like processes as we get new views.”

The new data is not only visually stunning, but provides previously unknown details about these lakes and the region. For example, Kraken Mare is more extensive and complex than previously thought. They also show nearly all of the lakes on Titan fall into an area covering about 600 miles by 1,100 miles (900 kilometers by 1,800 kilometers). Only 3 percent of the liquid at Titan falls outside of this area.

“Scientists have been wondering why Titan’s lakes are where they are. These images show us that the bedrock and geology must be creating a particularly inviting environment for lakes in this box,” said Randolph Kirk, a Cassini radar team member at the U.S. Geological Survey in Flagstaff, Ariz. “We think it may be something like the formation of the prehistoric lake called Lake Lahontan near Lake Tahoe in Nevada and California, where deformation of the crust created fissures that could be filled up with liquid.”

Additionally, scientists now know that Ligeia Mare is about 560 feet (170 meters) deep. This is the first time scientists have been able to plumb the bottom of a lake or sea on Titan. This was possible partly because the liquid turned out to be very pure, allowing the radar signal to pass through it easily. The liquid surface may be as smooth as the paint on our cars, and it is very clear to radar eyes.

“Ligeia Mare turned out to be just the right depth for radar to detect a signal back from the sea floor, which is a signal we didn’t think we’d be able to get,” said Marco Mastrogiuseppe, a Cassini radar team associate at Sapienza University of Rome. “The measurement we made shows Ligeia to be deeper in at least one place than the average depth of Lake Michigan.”

The new results indicate the liquid is mostly methane, somewhat similar to a liquid form of natural gas on Earth.

Sources: AGU press conference, JPL press release