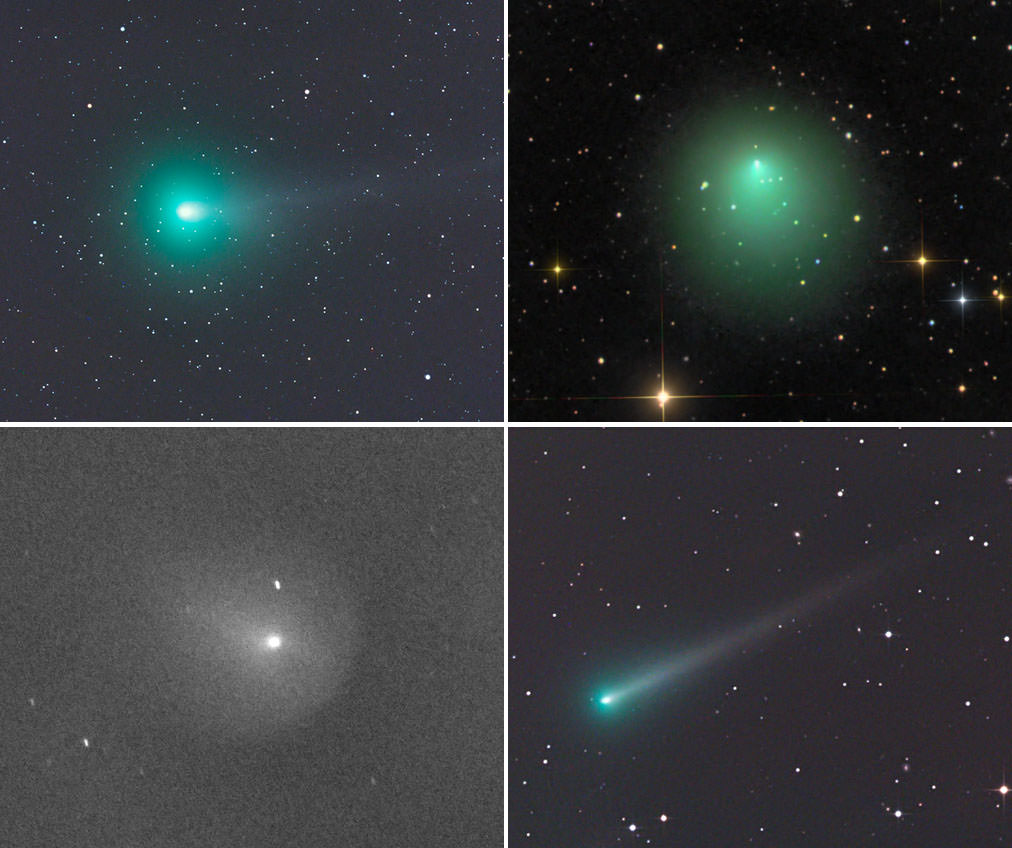

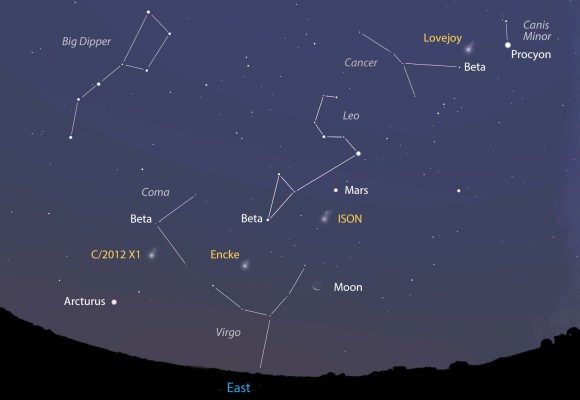

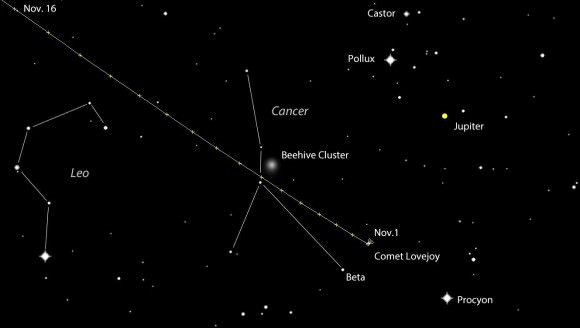

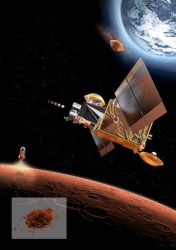

How did life on Earth originally develop from random organic compounds into living, evolving cells? It may have relied on impacts by enormous meteorites and comets — the same sort of catastrophic events that helped bring an end to the dinosaurs’ reign 65 million years ago. In fact, ancient impact craters might be precisely where life was able to develop on an otherwise hostile primordial Earth.

This is the hypothesis proposed by Sankar Chaterjee, Horn Professor of Geosciences and the curator of paleontology at the Museum of Texas Tech University.

“This is bigger than finding any dinosaur. This is what we’ve all searched for – the Holy Grail of science,” Chatterjee said.

Our planet wasn’t always the life-friendly “blue marble” that we know and love today. At one point early in its history it was anything but hospitable to life as we know it.

“When the Earth formed some 4.5 billion years ago, it was a sterile planet inhospitable to living organisms,” Chatterjee said. “It was a seething cauldron of erupting volcanoes, raining meteors and hot, noxious gasses. One billion years later, it was a placid, watery planet teeming with microbial life – the ancestors to all living things.”

Exactly how did this transition happen? That’s the Big Question in paleontology, and Chatterjee believes he may have found the answer lying within some of the world’s oldest and largest impact craters.

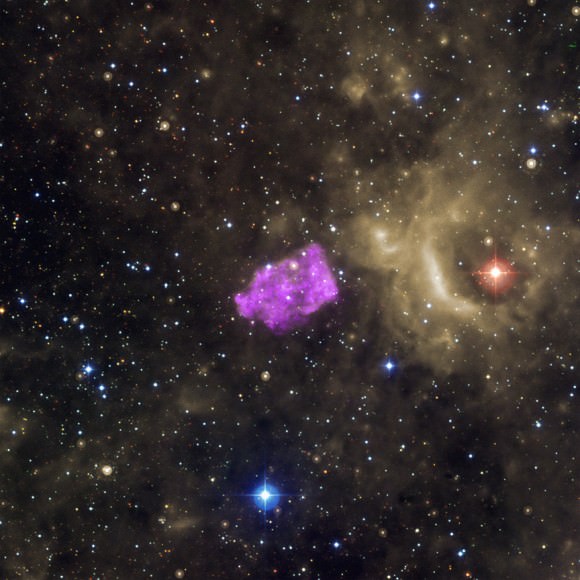

After studying the environments of the oldest known fossil-containing rocks in Greenland, Australia and South Africa, Chatterjee said these could be remnants of ancient craters and may be the very spots where life began in deep, dark and hot environments — similar to what’s found near thermal vents in today’s oceans.

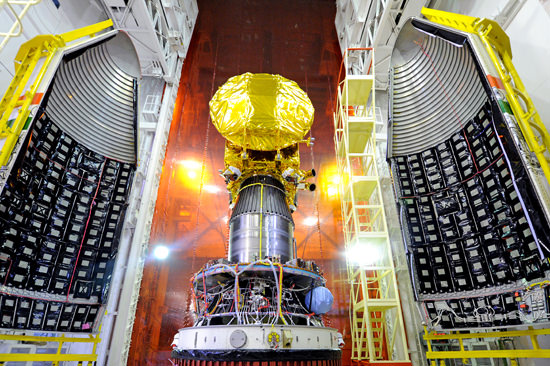

Larger meteorites that created impact basins of about 350 miles in diameter inadvertently became the perfect crucibles, according to Chatterjee. These meteorites also punched through the Earth’s crust, creating volcanically driven geothermal vents. They also brought the basic building blocks of life that could be concentrated and polymerized in the crater basins.

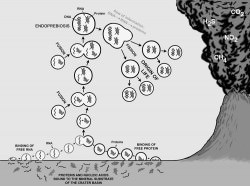

In addition to new organic compounds — and, in the case of comets, considerable amounts of water — impacting bodies may also have brought the necessary lipids needed to help protect RNA and allow it to develop further.

“RNA molecules are very unstable. In vent environments, they would decompose quickly. Some catalysts, such as simple proteins, were necessary for primitive RNA to replicate and metabolize,” Chatterjee said. “Meteorites brought this fatty lipid material to early Earth.”

Based on research in Australia by University of California professor David Deamer, the ingredients for all-important cell membranes were delivered to Earth via meteorites and existed in water-filled craters.

“This fatty lipid material floated on top of the water surface of crater basins but moved to the bottom by convection currents,” suggests Chatterjee. “At some point in this process during the course of millions of years, this fatty membrane could have encapsulated simple RNA and proteins together like a soap bubble. The RNA and protein molecules begin interacting and communicating. Eventually RNA gave way to DNA – a much more stable compound – and with the development of the genetic code, the first cells divided.”

And the rest, as they say, is history. (Well, biology really, and no small amount of chemistry and paleontology… and some astrophysics… well you get the idea.)

Chatterjee recognizes that further experiments will be needed to help support or refute this hypothesis. He will present his findings Oct. 30 during the 125th Anniversary Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America in Denver, Colorado.

Source: Texas Tech news article by John Davis