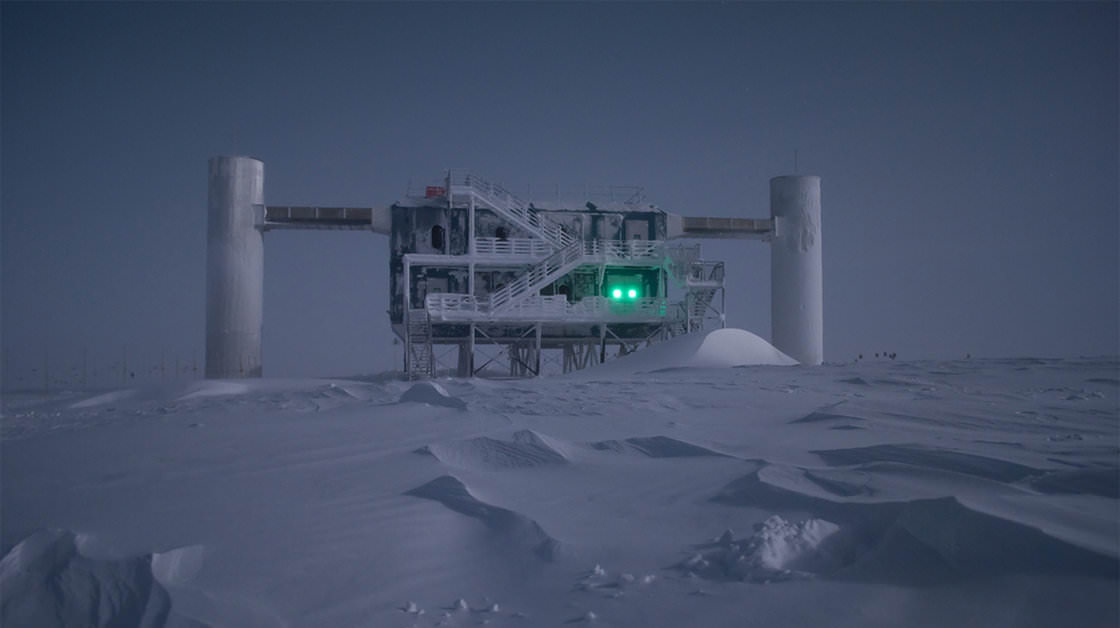

The IceCube neutrino observatory buried at the South Pole is one cool telescope. It has detected extremely high-energy neutrinos, which are elementary particles that likely originate outside our solar system. The discovery of 28 record-breaking neutrinos was announced earlier – with two of the particles — nicknamed Bert and Ernie – drawing particular attention because of the their off-the-chart energy of over 1,000,000,000,000,000 electron volts or 1 peta-electron volt (PeV).

Now, a new analysis of more recent data discovered 26 additional events beyond 30 teraelectronvolts — which exceeds the energy expected for neutrinos produced in the Earth’s atmosphere, and one of those events was almost double the energy of Bert and Ernie. This one has been dubbed “Big Bird,” and in combination, these events provide the first solid evidence for astrophysical neutrinos from distant cosmic accelerators, which might help us understand the origin of origin of cosmic rays. The detection has suggested a new age of astronomy is beginning, offering a new way to look at the Universe using high-energy neutrinos.

“While it is premature to speculate about the precise origin of these neutrinos, their energies are too high to be produced by cosmic rays interacting in the Earth’s atmosphere, strongly suggesting that they are produced by distant accelerators of subatomic particles elsewhere in our galaxy, or even farther away,” said Penn State Associate Professor of Physics Tyce DeYoung, the deputy spokesperson of the IceCube Collaboration.

High-energy neutrinos can pass through normal matter, and billions of neutrinos pass through the Earth every second. The vast majority of these are lower-energy particles that originate either in the Sun or in the Earth’s atmosphere. Far rarer are the high-energy neutrinos that more likely would have been created much farther from Earth in the most powerful cosmic events — gamma ray bursts, black holes, or the birth of stars. These neutrinos have been highly sought because they can carry information about the workings of the highest-energy and most-distant phenomena in the Universe.

“Scientists have been searching high and low for these super-energetic neutrinos using detectors buried under mountains, submerged in deep lakes and ocean trenches, lofted into the stratosphere by special balloons, and in the deep clear Antarctic ice at the South Pole,” said Doug Cowen, also from Penn State, who has worked on IceCube for over a decade. “To have finally seen them after all these years is immensely gratifying.”

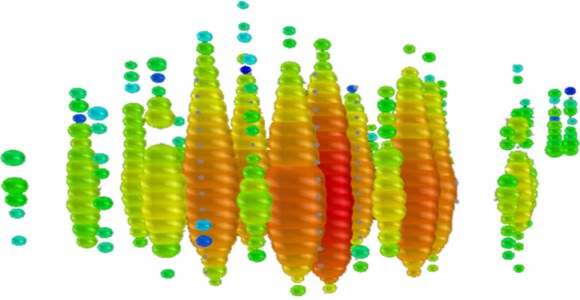

IceCube is located inside a cubic kilometer of ice beneath the South Pole and is comprised of more than 5,000 digital optical modules melted into in a cubic kilometer of ice at the South Pole. The observatory detects neutrinos through the fleeting flashes of blue light produced when a neutrino interacts with a water molecule in the ice.

The IceCube collaboration said they are continuing to refine and expand the search with new data and new analysis techniques, which may reveal additional high-energy events and possibly point to their astrophysical source or sources.

For more information, see the teams paper in Science, a free version is available on arXiv, press releases from Berkeley Labs, Penn State, and DESY. More information about the IceCube collaboration is here.