Move over Comet ISON. You’ve got company. Australian amateur astronomer Terry Lovejoy, discoverer of three previous comets, including the famous, long-tailed sungrazer C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy), just added a 4th to his tally.

This new comet will add to a lineup of comets that should grace early November skies in the northern hemisphere: Comets ISON, Encke and now the new Lovejoy.

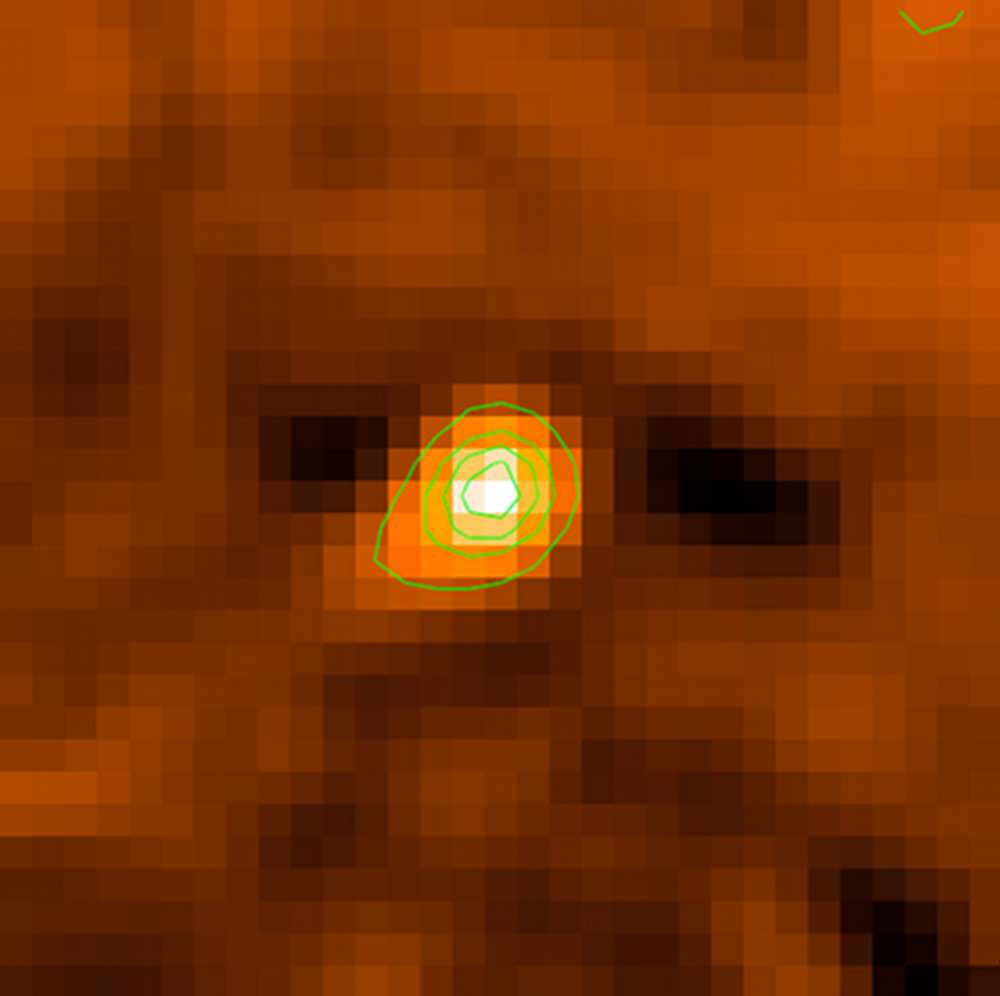

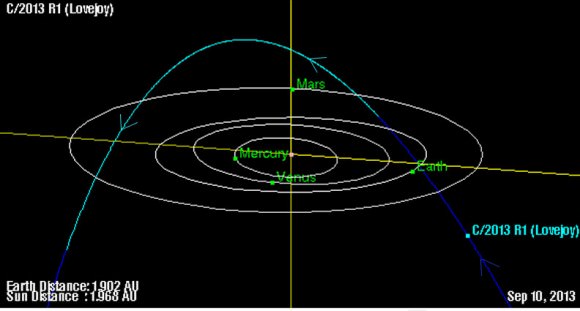

The discovery of C/2013 R1 Lovejoy was announced on Sept. 9 after two nights of photographic observations by Lovejoy with an 8-inch (20 cm) Schmidt-Cassegrain reflector. When nabbed, the comet was a faint midge of about 14.5 magnitude crossing the border between Orion and Monoceros. Subsequent observations by other amateur astronomers peg it a bit brighter at 14.0 with a small, condensed coma.

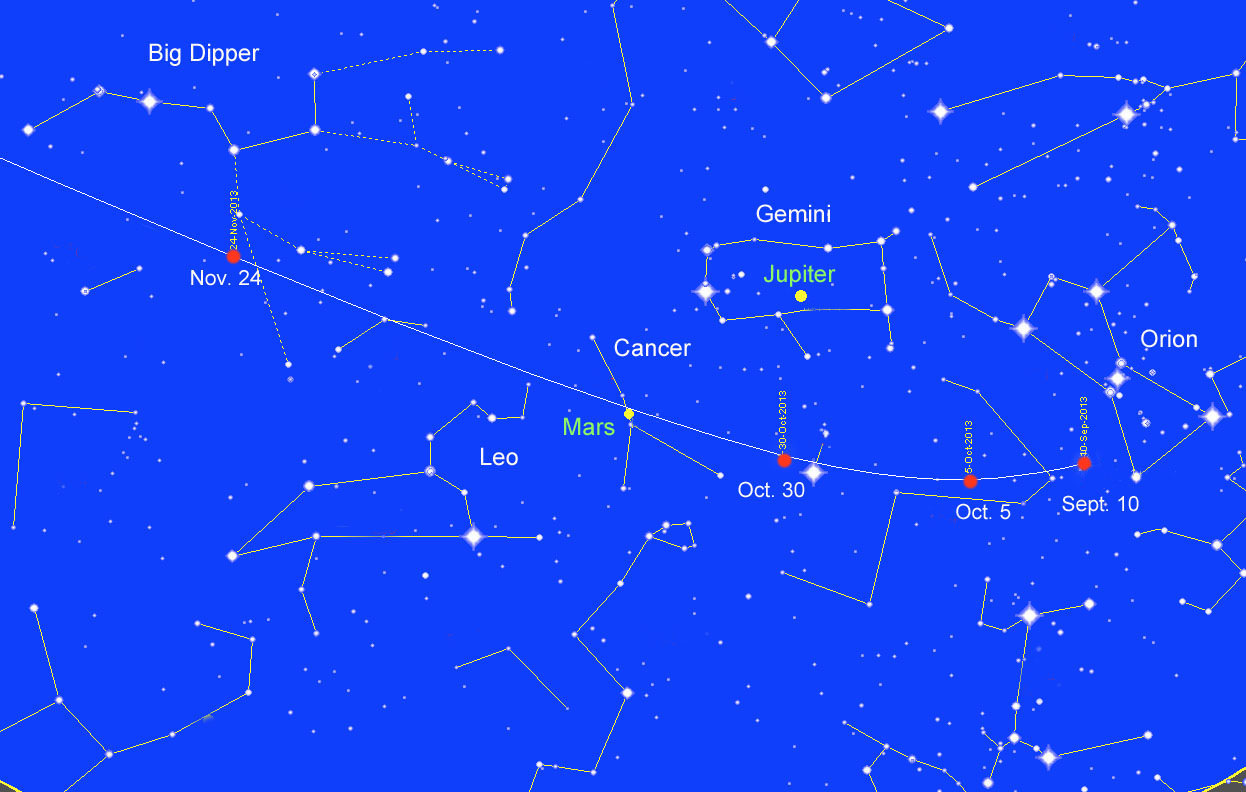

Right now you’ll need a hefty telescope to catch a glimpse of Lovejoy’s latest, but come November the comet will glow at around 8th magnitude, making it a perfect target for smaller telescopes. At closest approach on the Nov. 23, Lovejoy will pass 38.1 million miles (61.3 million km) from Earth while sailing across the Big Dipper at a quick pace.

Mid to late November is also the time when Comet ISON, the current focus of much professional and amateur observation, will be at its brightest in the morning sky at around magnitude 2-3. Get ready for some busy nights at the telescope!

C/2013 R1 will whip by the sun on Christmas Day at a distance of 81 million miles (130.3 million km) and then return back to the deeps from whence it came.

The charts here give you a general idea of its location and path over the next couple months. As the comet crosses into small-scope territory in early November, I’ll provide maps for you to find it.

And as Stuart Atkinson noted on his website, Cumbrian Sky a great lineup should be in the northern hemisphere skies on November 9, 2013. From the left, Comet Encke will be magnitude 6, ISON should be at about magnitude 6 or 7; then Mars, followed by the new Comet Lovejoy, which will be still very faint at around magnitude 9, topped off by a bright Jupiter. The comets will not likely be of naked eye visibility, but this should be a great chance for astrophotographer to capture this lineup!

Welcome to an exciting time for comet lovers, and congratulations Terry on another great discovery!