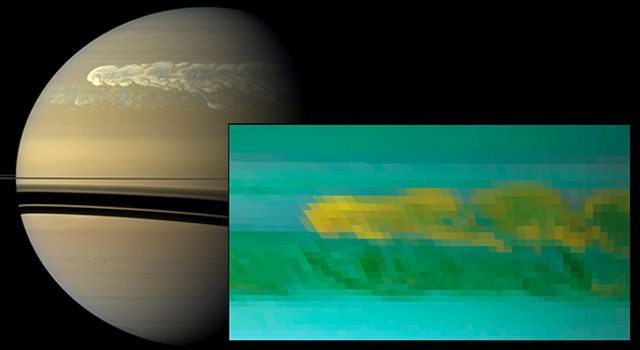

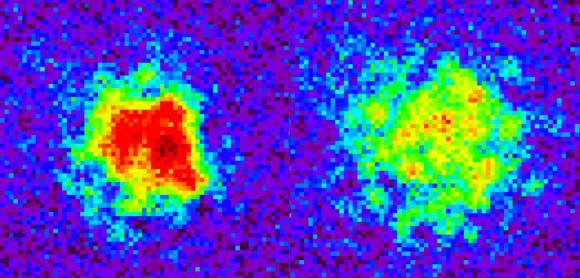

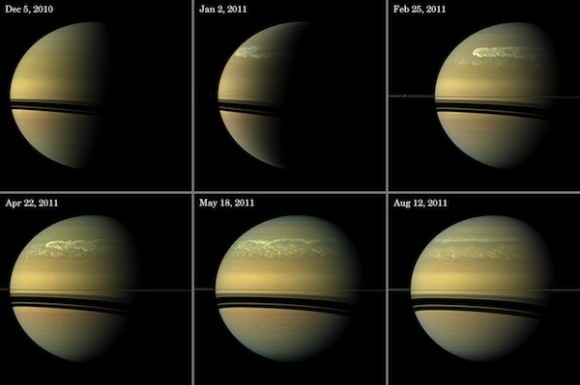

Remember the huge storm that erupted on Saturn in late 2010? It was one of the largest storms ever observed on the ringed planet, and it was even visible from Earth in amateur-sized telescopes. The latest research has revealed the tempestuous storm churned up something surprising deep within Saturn’s atmosphere: water ice. This is the first detection of water ice on Saturn, observed by the near-infrared instruments on the Cassini spacecraft.

“The new finding from Cassini shows that Saturn can dredge up material from more than 100 miles [160 kilometers],” said Kevin Baines, a co-author of the paper who works at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “It demonstrates in a very real sense that typically demure-looking Saturn can be just as explosive or even more so than typically stormy Jupiter.”

While Saturn’s moons have lots of water ice, Saturn is almost entirely hydrogen and helium, but it does have trace amounts of other chemicals, including water. When we look at Saturn, we’re actually seeing the upper cloud tops of Saturn’s atmosphere, which are made mostly of frozen crystals of ammonia.

Beneath this upper cloud layer, astronomers think there’s a lower cloud deck made of ammonium hydrosulfide and water. Astronomers thought there was water there, but not very much, and certainly not ice.

But the storm in 2010-2011 appears to have disrupted the various layers, lofting up water vapor from a lower layer that condensed and froze as it rose. The water ice crystals then appeared to become coated with more volatile materials like ammonium hydrosulfide and ammonia as the temperature decreased with their ascent, the authors said.

“The water could only have risen from below, driven upward by powerful convection originating deep in the atmosphere,” said Lawrence Sromovsky, also of the University of Wisconsin, who lead the research team. “The water vapor condenses and freezes as it rises. It then likely becomes coated with more volatile materials like ammonium hydrosulfide and ammonia as the temperature decreases with their ascent.

Big storms appear in the northern hemisphere of Saturn once every 30 years or so, or roughly once per Saturn year. The first hint of the most recent storm first appeared in data from Cassini’s radio and plasma wave subsystem on Dec. 5, 2010. Soon after that, it could be seen in images from amateur astronomers and from Cassini’s imaging science subsystem. The storm quickly grew to superstorm proportions, encircling the planet at about 30 degrees north latitude for an expanse of nearly 300,000 km (190,000 miles).

The researchers studied the dynamics of this storm, and realized that it worked like the much smaller convective storms on Earth, where air and water vapor are pushed high into the atmosphere, resulting in the towering, billowing clouds of a thunderstorm. The towering clouds in Saturn storms of this type, however, were 10 to 20 times taller and covered a much bigger area. They are also far more violent than an Earth storm, with models predicting vertical winds of more than about 300 mph (500 kilometers per hour) for these rare giant storms.

The storm’s ability to churn up water ice from great depths is evidence of the storm’s explosive power, the team said.

Their research will be published in the Sept. 9 edition of the journal Icarus.

Sources: University of Wisconsin-Madison, JPL