Opportunity starts Martian Mountaineering

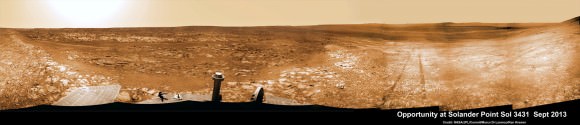

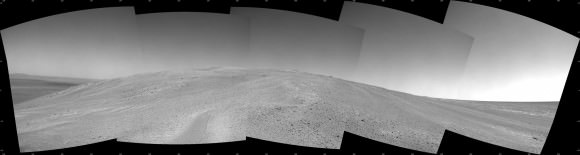

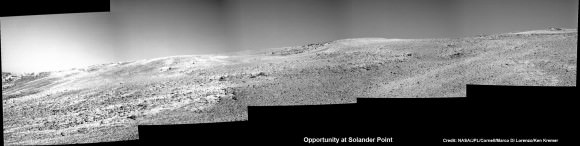

NASA’s Opportunity rover captured this southward uphill panoramic mosaic on Oct. 21, 2013 (Sol 3463) after beginning to ascend the northwestern slope of “Solander Point” on the western rim of Endeavour Crater – her 1st mountain climbing adventure. The northward-facing slope will tilt the rover’s solar panels toward the sun in the southern-hemisphere winter sky, providing an important energy advantage for continuing mobile operations through the upcoming winter. Assembled from Sol 3463 navcam raw images by Marco Di Lorenzo and Ken Kremer.

Credit: NASA/JPL/Cornell/Marco Di Lorenzo/Ken Kremer

Story and imagery updated[/caption]

NASA’s super resilient Opportunity robot has begun a new phase in her life on the Red Planet – Martian Mountaineer!

“This is our first real Martian mountaineering with Opportunity,” said the principal investigator for the rover, Steve Squyres of Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.

And it happened right in the middle of the utterly chaotic US government shutdown ! – that seriously harmed some US science endeavors. And at a spot destined to become a science bonanza in the months and years ahead – so long as she stays alive to explore ever more new frontiers.

On Oct. 8, mission controllers on Earth directed the nearly decade old robot to start the ascent of Solander Point – the northern tip of the tallest hill she has encountered after nearly 10 Earth years on Mars.

The northward-facing slopes at Solander also afford another major advantage. They will tilt the rover’s solar panels toward the sun in the southern-hemisphere winter sky, providing an important energy boost enabling continued mobile operations through the upcoming frigidly harsh winter- her 6th since landing in 2004.

Opportunity will first explore outcrops on the northwestern slopes of Solander Point in search of the chemical ingredients required to sustain life before gradually climbing further uphill to investigate intriguing deposits distributed amongst its stratographic layers.

The rover will initially focus on outcrops located in the lower 20 feet (6 meters) above the surrounding plains on slopes as steep as 15 to 20 degrees.

At some later time, Opportunity may ascend Solander farther upward, which peaks about 130 feet (40 meters) above the crater plains.

“We expect we will reach some of the oldest rocks we have seen with this rover — a glimpse back into the ancient past of Mars,” says Squyres.

NASA’s powerful Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) circling overhead recently succeeded in identifying clay-bearing rocks during new high resolution survey scans of Solander Point!

As I reported previously, the specially collected high resolution observations by the orbiters Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) were collected in August and being analyzed by the science team. They will be used to direct Opportunity to the most productive targets of interest

“CRISM data were collected,” Ray Arvidson told Universe Today. Arvidson is the mission’s deputy principal scientific investigator from Washington University in St. Louis, Mo.

“They show really interesting spectral features in the [Solander Point] rim materials.”

The new CRISM survey from Mars orbit yielded mineral maps which vastly improves the spectral resolution – from 18 meters per pixel down to 5 meters per pixel.

This past spring and summer, Opportunity drove several months from the Cape York rim segment to Solander Point.

“At Cape York, we found fantastic things,” Squyres said. “Gypsum veins, clay-rich terrain, the spherules we call newberries. We know there are even larger exposures of clay-rich materials where we’re headed. They might look like what we found at Cape York or they might be completely different.”

Opportunity rover captured mosaic on Oct. 21, 2013 (Sol 3463) after beginning to ascend the northwestern slope of “Solander Point” on the western rim of Endeavour Crater – her 1st mountain climbing adventure. Assembled from Sol 3463 pancam high resolution raw images by Marco Di Lorenzo and Ken Kremer. Credit: NASA/JPL/Cornell/Marco Di Lorenzo/Ken Kremer

Clay minerals, or phyllosilicates, form in neutral water that is more conducive to life.

At the base of Solander, the six wheeled rover discovered a transition zone between a sulfate-rich geological formation and an older formation. Sulfate-rich rocks form in a wet environment that was very acidic and less favorable to life.

Solander Point is located at the western rim of the vast expanse of Endeavour crater – some 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter.

Today marks Opportunity’s 3466th Sol or Martian Day roving Mars – for what was expected to be only a 90 Sol mission.

So far she has snapped over 185,200 amazing images on the first overland expedition across the Red Planet.

Her total odometry stands at over 23.89 miles (38.45 kilometers) since touchdown on Jan. 24, 2004 at Meridiani Planum.

Meanwhile, NASA is in the final stages of processing of MAVEN, the agencies next orbiter.

It is still scheduled to blast off from Cape Canaveral on Nov.18 – see my photos from inside the clean room at the Kennedy Space Center.

MAVEN’s launch was briefly threatened by the government shutdown.

On the opposite side of Mars, Opportunity’s younger sister rover Curiosity is trekking towards gigantic Mount Sharp and recently discovered a patch of pebbles formed by flowing liquid water.

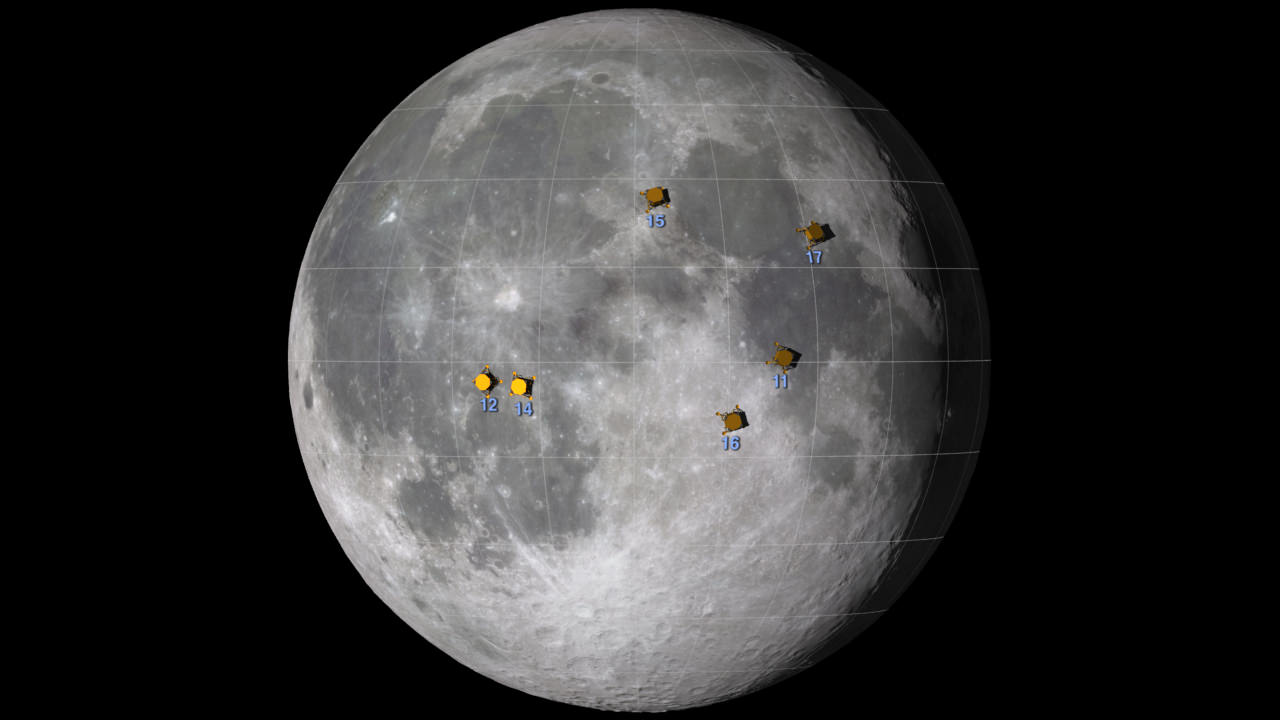

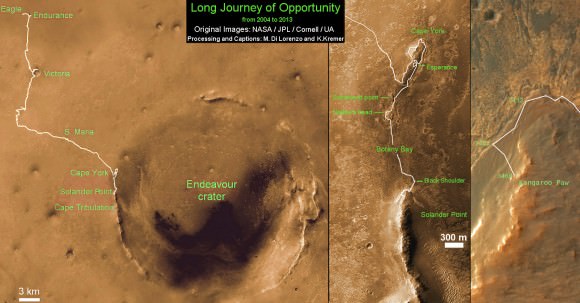

This map shows the entire path the rover has driven during nearly 10 years and over 3460 Sols, or Martian days, since landing inside Eagle Crater on Jan 24, 2004 to current location ascending her 1st Martian Mountain – Solander Point – at the western rim of Endeavour Crater. Opportunity discovered clay minerals at Esperance – indicative of a habitable zone and seeks clay minerals now at Solander. Credit: NASA/JPL/Cornell/ASU/Marco Di Lorenzo/Ken Kremer