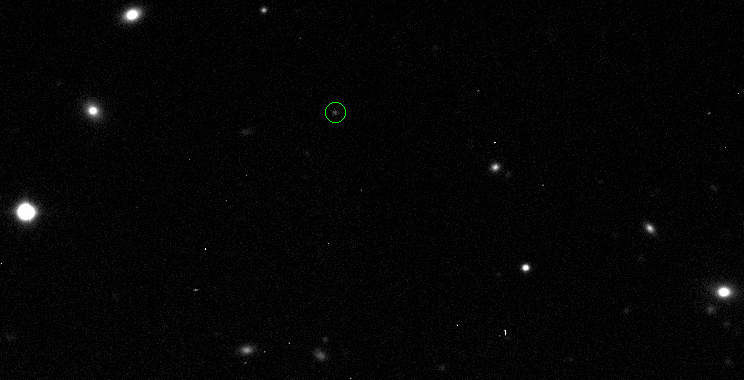

What’s new in the outer reaches of our solar system? Try the discovery of a Trojan asteroid orbiting Uranus. While a plethora of puns exist for this simple fact, the reality check is that this means there are far more of these objects out there than astronomers expected. The new Trojan even has a name – 2011 QF99!

A Trojan asteroid is a transient space rock which is temporarily captured by the gravity of a giant planet. It shares the planet’s orbital path, locked into a specific position known as a Lagrange point. What makes 2011 QF99 unusual is its presence in the outer solar system. Researchers found the scenario a bit unlikely. Why? The answer is simply because of planet size. According to theory, the strong gravitational pull of the larger neighboring planets should have destabilized any captured asteroid’s orbit and shot Uranian Trojans out of the neighborhood long ago.

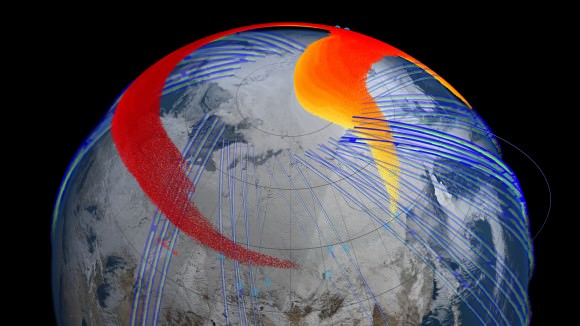

So just how did this 60 kilometer-wide conglomeration of ice and rock end up circling Uranus? Astronomers turned towards computer modeling for the answer. The research team, including UBC astronomers Brett Gladman, Sarah Greenstreet and colleagues at the National Research Council of Canada and Observatoire de Besancon in France, did a simulation of the solar system and its co-orbital objects – including Trojan asteroids. A short-term animation showing the motion of 2011 QF99, as seen from above the north pole of the solar system can be found here.

“Surprisingly, our model predicts that at any given time three percent of scattered objects between Jupiter and Neptune should be co-orbitals of Uranus or Neptune,” says Mike Alexandersen, lead author of the study to be published tomorrow in the journal Science.

Until now, no one had made any estimates on the percentage of possible outer solar system Trojans. Unexpectedly, the amount ended up being far greater than earlier estimates. Just over the last 10 years, several temporary Trojans and co-orbitals have been cataloged and 2011 QF99 is one of them. It made its home around Uranus within the last few hundred thousand years and will eventually – in about a million years – escape Uranus’ gravity.

“This tells us something about the current evolution of the solar system,” says Alexandersen. “By studying the process by which Trojans become temporarily captured, one can better understand how objects migrate into the planetary region of the solar system.”

Original Story Source: UBC News Release.