Just in case you haven’t seen this bit of awesome yet: Noctilucent clouds and aurora showed up together in skies over Scotland on the night of August 4/5, 2013. Maciej Winiarczyk from the Caithness Astronomy Group was on hand to capture it.

Enjoy!

Space and astronomy news

Just in case you haven’t seen this bit of awesome yet: Noctilucent clouds and aurora showed up together in skies over Scotland on the night of August 4/5, 2013. Maciej Winiarczyk from the Caithness Astronomy Group was on hand to capture it.

Enjoy!

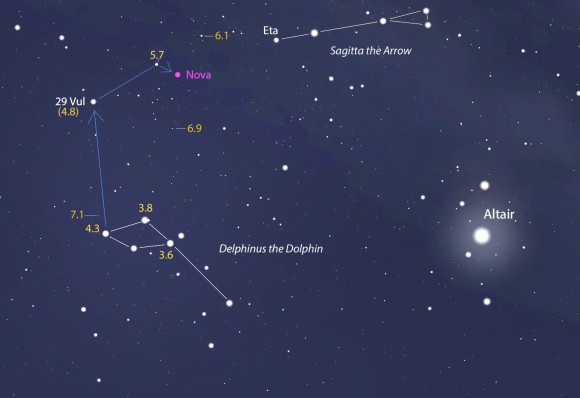

And now for something to appeal to your inner geek. Or, if you’re like me, your outer geek. Many of you have been watching the new nova in Delphinus with the naked eye and binoculars since it burst onto the scene early Aug. 14. In a moment I’ll show how to turn your observations into a cool representation of the nova’s behavior over time.

Where I live in northern Minnesota, we’ve had a lucky run of clear nights since the outburst began. Each night I’ve gone out with my 8×40 binoculars and star chart to estimate the nova’s brightness. The procedure is easy and straightforward. You find comparison stars near the nova with known magnitudes, then select one a little brighter and one a little fainter and interpolate between the two to arrive at the nova’s magnitude.

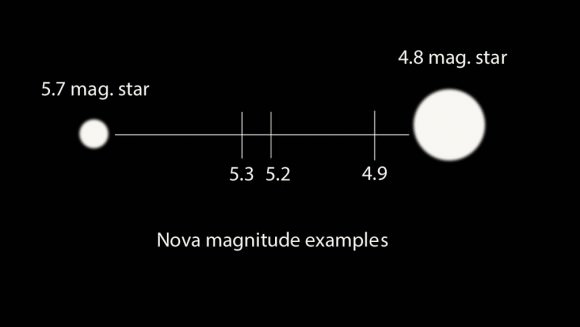

For example, if the nova’s brightness lies halfway between the magnitude 4.8 and 5.7 stars it’s about magnitude 5.3. The next night you might notice it’s not exactly halfway but a tad brighter or closer to the 4.8 star. Then you’d measure 5.2. Remember that the smaller the number, the brighter the object. I’ve found that defocusing the stars into disks makes it a bit easier to estimate these differences.

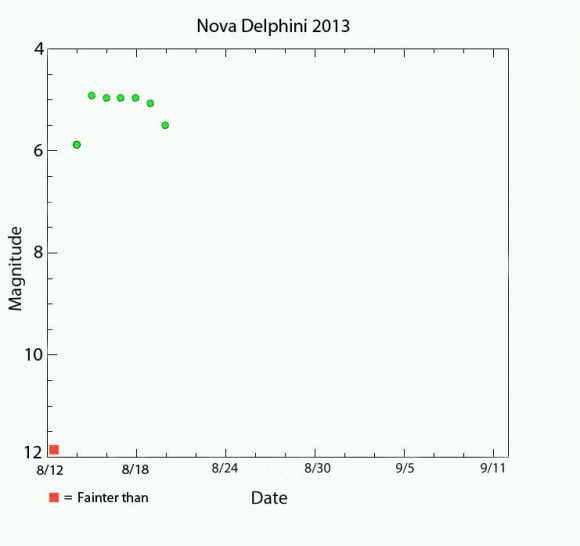

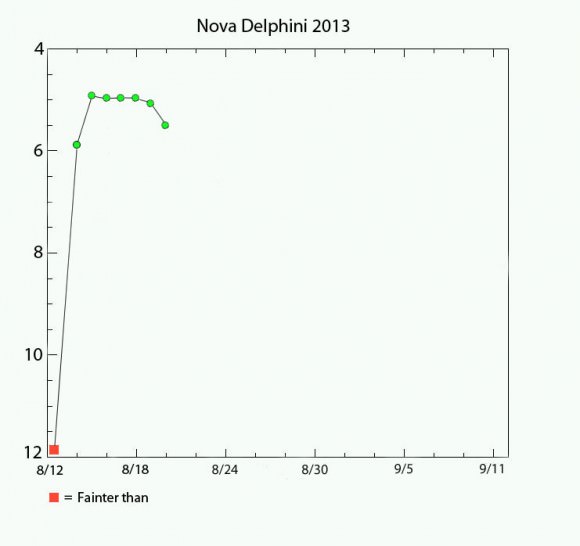

In time, you’ll come up with a list of magnitudes or brightness estimates for Nova Delphini. Here’s mine to date:

* Aug. 14: 5.8

* Aug. 15: 4.9

* Aug. 16: 5.0

* Aug. 17: 5.0

* Aug. 18: 5.0

* Aug. 19: 5.2

* Aug. 20: 5.5

So far just numbers, but there’s a way to turn this into a satisfying visual picture of the nova’s long-term behavior. Graph it! That’s what astronomers do, and they call it a light curve.

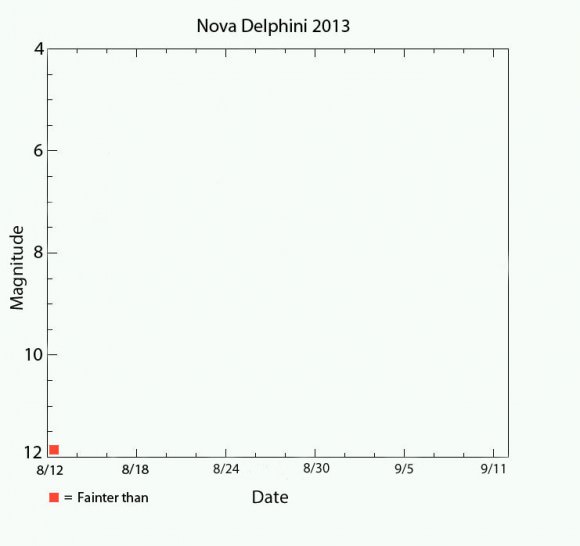

I dug around and came up with this very basic template. The horizontal or x-axis measures time in days, the vertical or y-axis plots the nova’s brightness measured in magnitudes. You can either right-click and save the image above or grab the higher-res version HERE.

Next, print out a copy and lay in your data points with pencil and ruler the old-fashioned way or use an imaging program like Photoshop or Paint to do the same on the computer. I use a very basic version of Photoshop Elements to plot my observations. Once your observations are marked, connect them to build your light curve.

Right away you’ll notice a few interesting things. The nova shot up from approximately 17th magnitude on Aug. 13 to 6.8 on Aug. 14 – a leap of more than 10 magnitudes, which translates to a nearly 10,000 fold increase in brightness.

I wasn’t able to see the Nova Del top out at around 4.4 magnitude – that happened when I was asleep the next morning – but I did catch it at 4.9. The next few days the nova hits a plateau followed by what appears for the moment like a steady decline in brightness. Will it rocket back up or continue to fade? That’s for you and your binoculars to find out the next clear night.

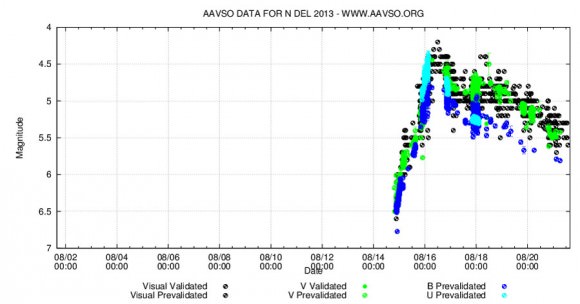

If you’d like to take the next step and contribute your observations for scientific use, head over to the AAVSO (American Assn. of Variable Star Observers) and become a member. Even if you don’t sign up, access to data, charts and light curves of novae and other variable stars is completely free.

I get a kick out of comparing my basic light curves with those created with thousands of observations contributed by hundreds of observers. The basic AAVSO curve looks all scrunched up for the moment because their time scale (x-axis) is much longer term than in my simple example. But guess what? You can change the scale using their light curve generator and open up the view a little more as I did in the curve above.

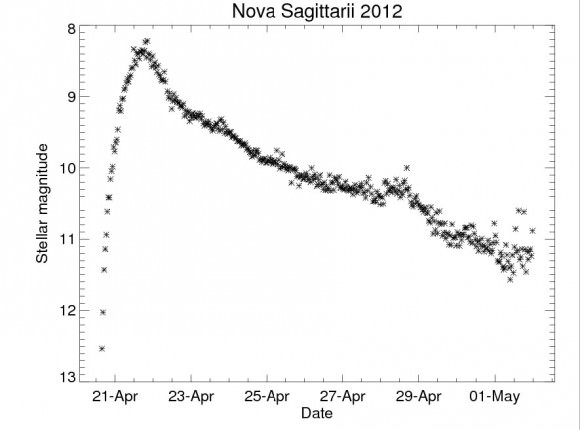

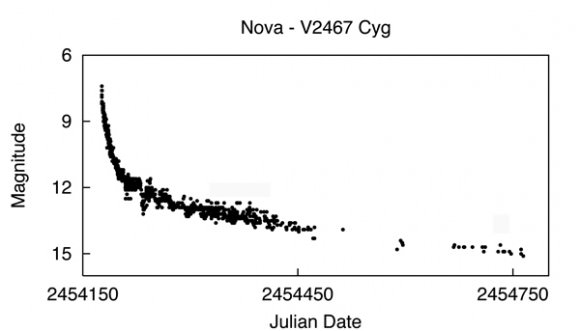

Here are a couple other typical novae light curves. By the time you’re done looking at the examples here as well as creating your own, you’ll gain a familiarity that may surprise you. Not only will be able to interpret trends in Nova Delphini’s brightness, but you’ll better understand the behavior of other variable stars at a glance. It’s as easy as connecting the dots.

Routines. They tell you when to get up in the morning, what to do at your day job and how to handle myriad tasks ranging from house cleaning to using a computer. Memorizing these procedures makes it a lot easier to handle things that come up in life.

In space, establishing routines is even more important because they will help guide your thinking during an emergency. That’s why astronauts spend thousands of hours learning, simulating and memorizing before heading up to space.

European Space Agency astronaut Alexander Gerst, who will fly to the International Space Station in 2014 during Expedition 40/41, gave Universe Today some insight on how it’s done.

Why train so often? According to Gerst, practicing an emergency procedure on the ground makes it easier to think clearly during a situation up in space. An astronaut’s reaction to any problem on station — a fire, a depressurization, toxic air — is to begin with the procedures. “They sink in and become a memorized response or a natural reaction,” he said. In a fire situation, for example, “Immediately when you hear the sound of the alarm, I will grab the nearest gas mask and the nearest emergency book and head to our control post, which is part of the emergency response.” (Chris Cassidy, a former Navy SEAL on station right now, had more to say to Universe Today in March about “muscle memory” during emergencies.)

What’s the biggest challenge? The complexity of the station. The American and Russian sides have different procedures and different equipment. There are three types of gas masks on station, for example, and three kinds of fire extinguishing systems. (According to Gerst, all but the most stubborn fires on station are extinguished after cutting ventilation and electricity to the affected area.) To address the complexity, the astronauts spend hours in the classroom discussing what to look for in the fire sensors, pressure sensors, ammonia sensors and other parts of the vehicle. The signatures look different for depressurizations, fires and other conditions in space and it’s key to know what they mean at a glance.

What happens during a simulation? After discussing what actions to take, it’s time to play them out. “We don’t light our modules on fire, but the trainers are creative in creating that [emergency] condition,” Gerst said. Sometimes smoke machines will be used during a fire simulation, for example, or the astronauts will simply be informed by instructors that there is a fire in a section of the station. As the astronauts go through the procedures, trainers keep an eye on them and give feedback. In more complex situations, 10 to 20 flight controllers can join in to simulate communications with Mission Control in Houston or its equivalent in Russia.

What about dealing with emergencies in a smaller spacecraft? Astronauts can spend anywhere from hours to days on a Russian Soyuz getting to and from the station. If there’s a fire on board, the three people squashed inside the capsule wouldn’t have much room to deploy fire extinguishers. The response is essentially for astronauts to slam shut the visors on their spacesuits and vent the spacecraft. During a depressurization, the procedure is also to close the visor. “You don’t even have to get out of your seat to deal with the emergency, which makes it quite different,” Gerst said.

What about emergencies during a spacewalk? Astronauts spend hundreds of hours inside the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory in Houston, a huge pool with a mockup of most of the International Space Station inside. They practice spacewalk procedures such as how to bring an unconscious crew member back to the airlock, or what to do if air leaks out of a spacesuit. Gerst credits this sort of training for helping out during a recent incident involving fellow ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano. In July, emergency procedures kicked in for real when Parmitano’s spacesuit sprung a water leak during a spacewalk. In a nutshell, the crew worked to bring Parmitano back inside as quickly as possible, which led to a safe (but early) end to the work. (Read Parmitano’s nail-biting first-hand account of the incident here.)

What’s the big takeaway? Gerst emphasizes that emergency training is a “huge topic”. He and Reid Wiseman recently got checked out for emergency procedures on the United States side of the station, only to fly to Moscow and then have to do the same thing for the Russian side in mid-August. And there’s other training to do as well — another huge topic is medical emergencies , which Gerst practiced in a German hospital in July.

On July 16, Expedition 36 astronauts Chris Cassidy and Luca Parmitano had to cut a planned 7-hour spacewalk short after only an hour and a half due to a malfunction in Parmitano’s space suit, leaking water into his helmet and eventually cutting off his vision, hearing, and communications. Fortunately the Italian test pilot was able to safely return inside the ISS, but for several minutes he was faced with a pretty frightening situation: stuck outside Space Station with his head in a fishbowl that was rapidly filling with water.

On August 20, he shared his personal account of the event on his ESA blog.

“The only idea I can think of is to open the safety valve by my left ear: if I create controlled depressurisation, I should manage to let out some of the water, at least until it freezes through sublimation, which would stop the flow. But making a ‘hole’ in my spacesuit really would be a last resort…”

Parmitano’s description of his suit mishap begins as I’m sure all spacewalks do: with a sense of energy and enthusiasm for a job about to be performed in a challenging yet exotic and undeniably privileged location.

“My eyes are closed as I listen to Chris counting down the atmospheric pressure inside the airlock – it’s close to zero now. But I’m not tired – quite the reverse! I feel fully charged, as if electricity and not blood were running through my veins. I just want to make sure I experience and remember everything. I’m mentally preparing myself to open the door because I will be the first to exit the Station this time round. Maybe it’s just as well that it’s night time: at least there won’t be anything to distract me.”

But even though the EVA initially progressed as planned — ahead of schedule, in fact — it soon became obvious to Parmitano that something was amiss with his suit.

“The unexpected sensation of water at the back of my neck surprises me – and I’m in a place where I’d rather not be surprised. I move my head from side to side, confirming my first impression, and with superhuman effort I force myself to inform Houston of what I can feel, knowing that it could signal the end of this EVA.”

It didn’t take long before an uncomfortable situation escalated into something potentially very dangerous.

“As I move back along my route towards the airlock, I become more and more certain that the water is increasing. I feel it covering the sponge on my earphones and I wonder whether I’ll lose audio contact. The water has also almost completely covered the front of my visor, sticking to it and obscuring my vision. I realise that to get over one of the antennae on my route I will have to move my body into a vertical position, also in order for my safety cable to rewind normally. At that moment, as I turn ‘upside-down’, two things happen: the Sun sets, and my ability to see – already compromised by the water – completely vanishes, making my eyes useless; but worse than that, the water covers my nose – a really awful sensation that I make worse by my vain attempts to move the water by shaking my head. By now, the upper part of the helmet is full of water and I can’t even be sure that the next time I breathe I will fill my lungs with air and not liquid. To make matters worse, I realise that I can’t even understand which direction I should head in to get back to the airlock. I can’t see more than a few centimetres in front of me, not even enough to make out the handles we use to move around the Station.”

After contemplating opening a hole in his helmet to let out some of the water — a “last resort,” indeed — Parmitano managed to get back inside the airlock with help from Cassidy. But he still had to deal with the process of repressurization, which itself takes a few minutes.

Read more: Space Water Leak Prompts NASA Mishap Investigation

“I try to move as little as possible to avoid moving the water inside my helmet. I keep giving information on my health, saying that I’m ok and that repressurization can continue. Now that we are repressurizing, I know that if the water does overwhelm me I can always open the helmet. I’ll probably lose consciousness, but in any case that would be better than drowning inside the helmet.”

Now, a month after the mishap, Parmitano reflects on the nature of the event and of space travel in general.

“Space is a harsh, inhospitable frontier and we are explorers, not colonisers. The skills of our engineers and the technology surrounding us make things appear simple when they are not, and perhaps we forget this sometimes.”

“Better not to forget,” he advises.

Read Luca’s full blog post on the ESA site here.

ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano is the first of ESA’s new generation of astronauts to fly into space. Luca will serve as flight engineer on the Station for Expeditions 36 and 37. He qualified as a European astronaut and was proposed by Italy’s ASI space agency for this mission.

Being selected to (potentially) go on a mission outside of Earth orbit has to be exciting. Assuming the astronaut title, however, brings some tough career choices.

“It’s truly starting at square one,” said Anne McClain, a major in the U.S. Army. She spoke in a televised press conference today (Tuesday) introducing NASA’s newest class of astronaut candidates to the media.

“All of us were in our careers, and we were really in places where we started to be leaders in those careers. Now, our biggest responsibility is to learn from all these people around us, and from years and years of history at NASA so that when that baton does get passed to us, we’re ready to move forward.”

It was the first time NASA’s astronaut candidates — eight Americans, comprising four men and four women — spoke to journalists since their selection. NASA has been heavily promoting this group on Facebook, Twitter and other forms of social media, positioning these new employees in tune with the agency’s desire to retrieve asteroids and generally push on to exploration outside of Earth’s orbit.

The astronauts emphasized the years of effort it took to get to their positions today, with McClain adding it’s best to choose a career you’re passionate about just in case the odds aren’t in your favor. (To put this in perspective, the eight people selected were from more than 6,000 applicants, pegging anyone’s chance of getting in at far less than 1%).

Nevertheless, many of them have been working at it since childhood. Andrew Morgan, also a U.S. Army major, recalled writing to Apollo astronaut Alan Bean when Morgan was in fourth grade (making him about eight or nine years old at the time).

“I received several weeks later a letter in the mail. It was addressed from NASA and I was convinced that that was my acceptance as an astronaut candidate,” Morgan said as laughter came from the audience. “From that day forward, if I had to peg a point, it was that point. It was a letter from Alan Bean that made that difference for me.”

Getting selected was an 18-month process. From the thousands of applications, the top 120 were selected for initial interviews and medical screening and then brought down to a shortlist of 49 that had more detailed evaluations (including team-building exercises).

It was serious work, but there was time for a little fun along the way.

“We were asked to compose a tweet, a limerick or a haiku,” said Victor Glover (a lieutenant-commander in the U.S. Navy) of one writing test during the selection process. His, a limerick, poked fun at the extensive medical testing:

Eyes fixed, gazing off into space

My mind in awe of the human race

This is all dizzying to me

Because I gave so much blood and pee

Happy to be here (at) the colonoscopy place.

We won’t hear much from the astronaut candidates in the next two years as they learn the basics about how the space station works and undergo basic or supplemental flight training in T-38s. In the meantime, you can read more about the candidates on this NASA web hub.

Want to be a government astronaut yourself? Here are some sample guidelines from NASA, the Canadian Space Agency, the European Space Agency and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency. Other active astronaut programs include China and Russia.

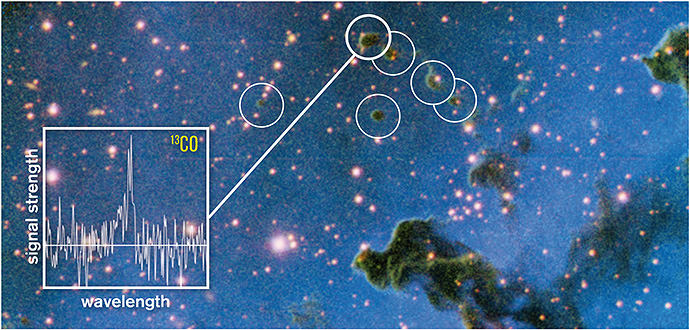

Free-floating rogue planets are intriguing objects. These planet-sized bodies adrift in interstellar space were predicted to exist in 1998, and since 2011 several orphan worlds have finally been detected. The leading theory on how these nomadic planets came to exist is that they were they ejected from their parent star system. But new research shows that there are places in interstellar space that might have the right conditions to form planets — with no parent star required.

Astronomers from Sweden and Finland have found tiny, round, cold clouds in space that may allow planets to form within, all on their own. In a sense, planets could be born free.

Continue reading “Rogue Planets Could Form On Their Own in Interstellar Space”

Looking for a new desktop background? This might do nicely: a photo of noctilucent “night-shining” clouds seen above a midnight Sun over Alaska, taken from the ISS as it passed over the Aleutian Islands just after midnight local time on Sunday, August 4.

When this photo was taken Space Station was at the “top of the orbit” — 51.6 ºN, the northernmost latitude that it reaches during its travels around the planet.

According to the NASA Earth Observatory site, “some astronauts say these wispy, iridescent clouds are the most beautiful phenomena they see from orbit.” So just what are they? Read on…

Found about 83 km (51 miles) up, noctilucent clouds (also called polar mesospheric clouds, or PMCs) are the highest cloud formations in Earth’s atmosphere. They form when there is just enough water vapor present to freeze into ice crystals. The icy clouds are illuminated by the Sun when it’s just below the horizon, after darkness has fallen or just before sunrise, giving them their eponymous property.

Noctilucent clouds have also been associated with rocket launches, space shuttle re-entries, and meteoroids, due to the added injection of water vapor and upper-atmospheric disturbances associated with each. Also, for some reason this year the clouds appeared a week early.

Read more: Noctilucent Clouds — Electric Blue Visitors from the Twilight Zone

Some data suggest that these clouds are becoming brighter and appearing at lower latitudes, perhaps as an effect of global warming putting more greenhouse gases like methane into the atmosphere.

“When methane makes its way into the upper atmosphere, it is oxidized by a complex series of reactions to form water vapor,” said James Russell, the principal investigator of NASA’s Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere (AIM) project and a professor at Hampton University. “This extra water vapor is then available to grow ice crystals for NLCs.”

A comparison of noctilucent cloud formation from 2012 and 2013 has been compiled using data from the AIM spacecraft. You can see the sequence here.

And for an incredible motion sequence of noctilucent clouds — taken from down on the ground — check out the time-lapse video below by Maciej Winiarczyk, coincidentally made at around the same time as the ISS photo above:

(The video was featured as the Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD) for August 19, 2013.)

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

Fans of Mars and spaceflight waxed poetic as the haiku selected to travel to Mars aboard the MAVEN spacecraft were announced earlier this month.

The contest received 12,530 valid entries from May 1st through the contest cutoff date of July 1st. Students learned about Mars, planetary exploration and the MAVEN mission as they composed haiku ranging from the personal to the insightful to the hilarious.

“The contest has resonated with people in ways that I never imagined! Both new and accomplished poets wrote poetry to reflect their views of Earth and Mars, their feelings about space exploration, their loss of loved ones who have passed on, and their sense of humor,” said Stephanie Renfrow, MAVEN Education & Public Outreach & Going to Mars campaign lead.

A total of 39,100 votes were cast in the contest; all entries receiving more than 2 votes (1,100 in all) will be carried on a DVD affixed to the MAVEN spacecraft bound for Martian orbit.

Five poems received more than a thousand votes. Among these were such notables as that of one 8th grader from Denver Colorado, who wrote;

Phobos & Deimos

Moons orbiting around Mars

Snared by Gravity

Another notable entry which was among the poems sited for special recognition by the MAVEN team was that of Allison Swets of Michigan;

My body can’t walk

My mouth can’t make words but I

Soar to Mars today

377 artwork entries were also selected to fly aboard MAVEN as well.

Didn’t get picked? There’s still time to send your name aboard MAVEN along with thousands that have already been submitted. You’ve got until September 10!

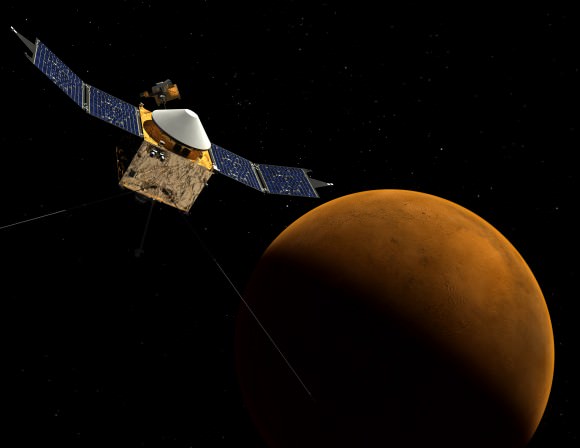

Part of NASA’s discontinued Scout-class of missions, the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN mission, or MAVEN, is due to launch out of Cape Canaveral on November 18th, 2013. Selected in 2008, MAVEN has a target cost of less than $500 million dollars US, not including launch carrier services atop an Atlas V rocket in a 401 flight configuration.

The Phoenix Lander was another notable Scout-class mission that was extremely successful, concluding in 2008.

Principal investigator for MAVEN is the University of Boulder at Colorado’s Bruce Jakosky of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP).

The use of poetry to gain public interest in the mission is appropriate, as MAVEN seeks to solve the riddle that is the Martian atmosphere. How did Mars lose its atmosphere over time? What role does the solar wind play in stripping it away? And what is the possible source of that anomalous methane detected by Mars Global Surveyor from 1999 to 2004?

MAVEN is based on the design of the Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft. It will carrying an armada of instruments, including a Neutral Gas & Ion Mass Spectrometer, a Particle and Field Package with several analyzers, and a Remote Sensing Package built by LASP.

MAVEN just arrived at the Kennedy Space Center earlier this month for launch processing and mating to its launch vehicle. Launch will be out of Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on November 18th with a 2 hour window starting at 1:47 PM EST/ 18:47 UT.

Assuming that MAVEN launches at the beginning of its 20 day window, it will reach Mars for an orbital insertion on September 22, 2014. MAVEN will orbit the Red Planet in an elliptical 150 kilometre by 6,200 kilometre orbit, joining the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the European Space Agencies’ Mars Express and the aging Mars Odyssey orbiter, which has been surveying Mars since 2001.

The window for an optimal launch to Mars using a minimal amount of fuel opens every 24 to 26 months. During the last window of opportunity in 2011, the successful Mars Curiosity rover and the ill-fated Russian mission Phobos-Grunt sought to make the trip.

This time around, MAVEN will be joined by India’s Mars Orbiter Mission, launching from the Satish Dhawan Space Center on October 21st. If successful, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) will join Russia, ESA & NASA in nations that have successfully launched missions to Mars.

This window comes approximately six months before Martian opposition, which next occurs on April 8th, 2014. In 2016, ESA’s ExoMars Mars Orbiter and NASA’s InSight Lander will head to Mars. And 2018 may see the joint ESA/NASA ExoMars rover and… if we’re lucky, Dennis Tito’s proposed crewed Mars 2018 flyby.

Interestingly, MAVEN also arrives in Martian orbit just a month before the close 123,000 kilometre passage of comet C/2013 A1 Siding Spring, although as of this time, there’s no word if it will carry out any observations of the comet.

These launches will also represent the first planetary missions to depart Earth since 2011. You can follow the mission as @MAVEN2Mars on Twitter. We’ll also be attending the MAVEN Conference and Workshop this weekend in Boulder and tweeting our adventures (wi-fi willing) as @Astroguyz. We also plan on attending the November launch in person as well!

And in the end, it was perhaps for the good of all mankind that our own rule-breaking (but pithy) Mars haiku didn’t get selected:

Rider of the Martian Atmosphere

Taunting Bradbury’s golden-bee armed Martians

While dodging the Great Galactic Ghoul

Hey, never let it be said that science writers make great poets!

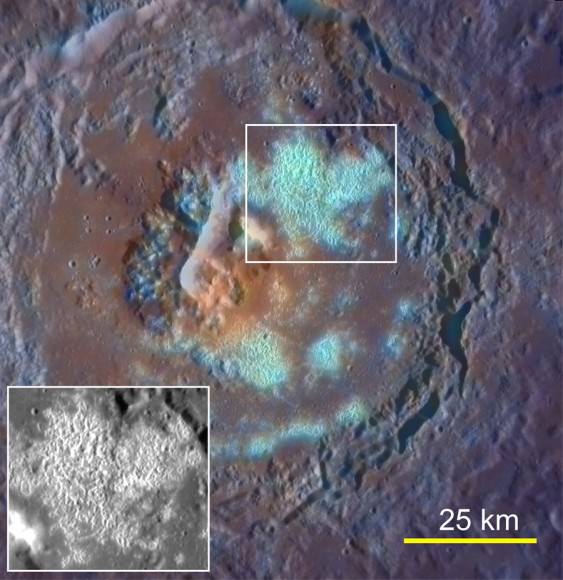

Here’s a rather interesting view from orbit around the innermost planet: Mercury’s Tyagaraja crater, the interior of which is seen here in an oblique-angled image acquired by the MESSENGER spacecraft on November 12, 2011 (and released August 16, 2013.)

This view looks west across the northern portion of the 97-kilometer (60-mile) -wide crater, and shows some of its large central peaks, terraced walls, and bright erosion features called hollows that are spread across a wide swath of its interior.

First seen by MESSENGER in 2011, hollows are thought to indicate an erosion process unique to Mercury because of its composition and close proximity to the Sun. The lack of craters within hollows seems to indicate that they are relatively young features… in fact, they may be part of a process that continues today.

This image was acquired as a high-resolution targeted observation. Targeted observations are images of a small area on Mercury’s surface at resolutions much higher than the 200-meter/pixel morphology base map.

Tyagaraja is named after Kakarla Tyagabrahmam, an 18th-century composer of classical Indian Carnatic music.

Read more on the MESSENGER website here.

Images: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington

Up until 20 years ago, the only planets astronomers were aware of were within our Solar System. They assumed others were out there, but none had ever been detected.

Today we know of almost a thousand planets orbiting other stars. They come in a wide variety of sizes. Some are smaller than Earth, and others are more massive than Jupiter. Some are found around solitary stars, while others are located in multiple star systems. In those systems, there can be individual or even multiple planets in orbit. In fact, recent surveys suggest there are planets orbiting every single star in the Milky Way.

So, what methods do astronomers use to find these “extrasolar planets”?

The first extrasolar planet was discovered in 1991.

It was found orbiting a pulsar, a dead star that rotates rapidly, firing out bursts of radiation on an eerily precise interval. As the planets orbit the pulsar, they pull it back and forth with their gravity. This slightly changes the wavelength of the radiation bursts streaming from the exotic star. Astronomers were able to measure these changes, and calculate the orbits of multiple planets.

Radial Velocity Method

That something, was a planet.

In fact, this planet was unlike anything we have in the Solar System. 51 Pegasi B has about half the mass of Jupiter and it orbits much closer to its parent star. Closer even, than Mercury to the Sun.

Until this discovery, astronomers didn’t think it was possible for planets to orbit this close, and have had to revise their theories on planetary formation. Many Hot Jupiter planets have been discovered since, some in even more extreme environments.

Gravitational Microlensing

Amateur astronomers around the world participate in microlensing studies, imaging stars quickly when an event is announced.

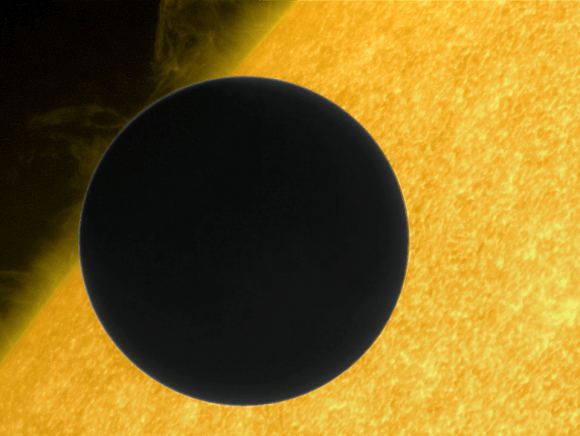

Transit Method

The most successful way of finding planets is the transit method.

This is where telescopes measure the total amount of light coming from a star, and detect a slight variation in brightness as a planet passes in front.

Using this technique, NASA’s Kepler Mission has turned up thousands of candidate planets. Including some less massive than Earth, and others in the star’s habitable zone.

From the Kepler data, It’s just a matter of time before the holy grail of planets is uncovered… an Earth-sized world, orbiting a Sun-like star within the habitable zone.

All of these techniques are limited as they require the planets to be orbiting directly between us and their star. If the planets orbit above or below this plane, we just can’t detect them.

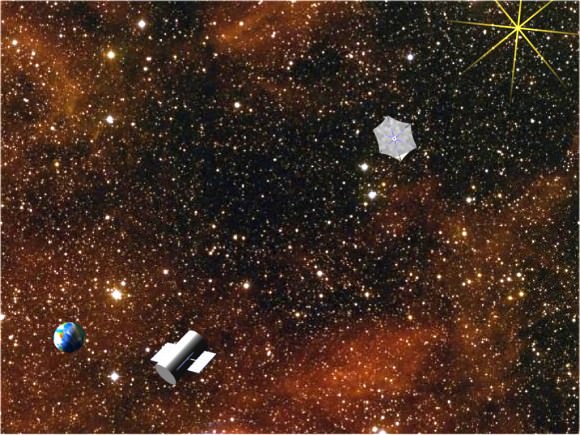

Coronographs

Imagine if you could block all the light from the star, and only see the planets in orbit. This technique has been used for observing the Sun’s atmosphere, but it requires much more precision to see distant stars.

One idea is to position a sunflower-shaped starshade in space, 125,000 km away from the observing telescope. This shade would just cover the star, dimming it by a factor of 10-billion. Light from the planets would leak around the edges.

A sophisticated instrument could even study the atmospheres of these planets, and possibly provide us with evidence of life.

We’re at an exciting time in the field of extrasolar planet research, and trust me, these clever astronomers are just getting started.