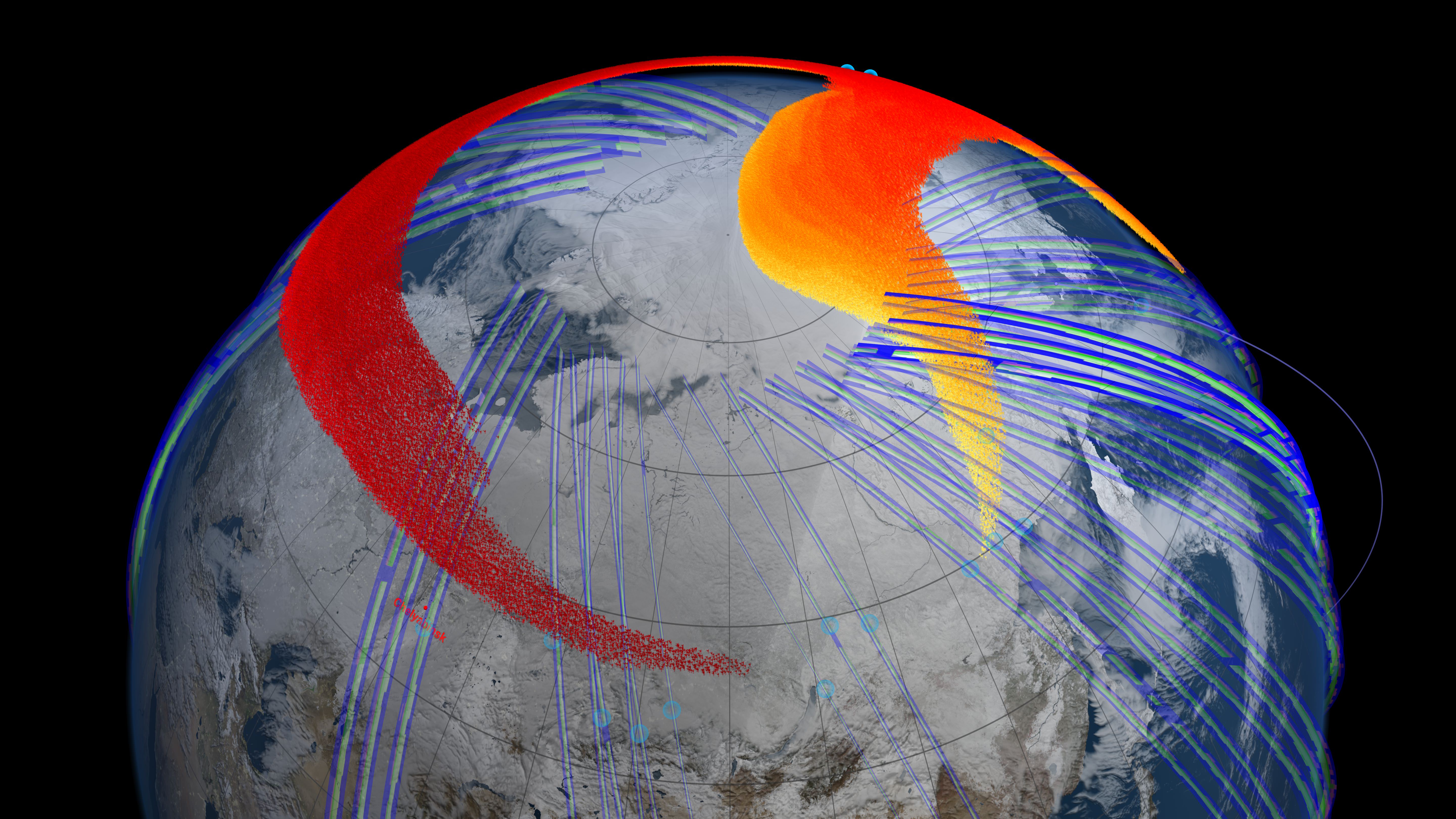

When a meteor weighing 10,000 metric tons exploded 22.5 km (14 miles) above Chelyabinsk, Russia on Feb. 15, 2013, the news of the event spread quickly around the world. But that’s not all that circulated around the world. The explosion also deposited hundreds of tons of dust in Earth’s stratosphere, and NASA’s Suomi NPP satellite was in the right place to be able to track the meteor plume for several months. What it saw was that the plume from the explosion spread out and wound its way entirely around the northern hemisphere within four days.

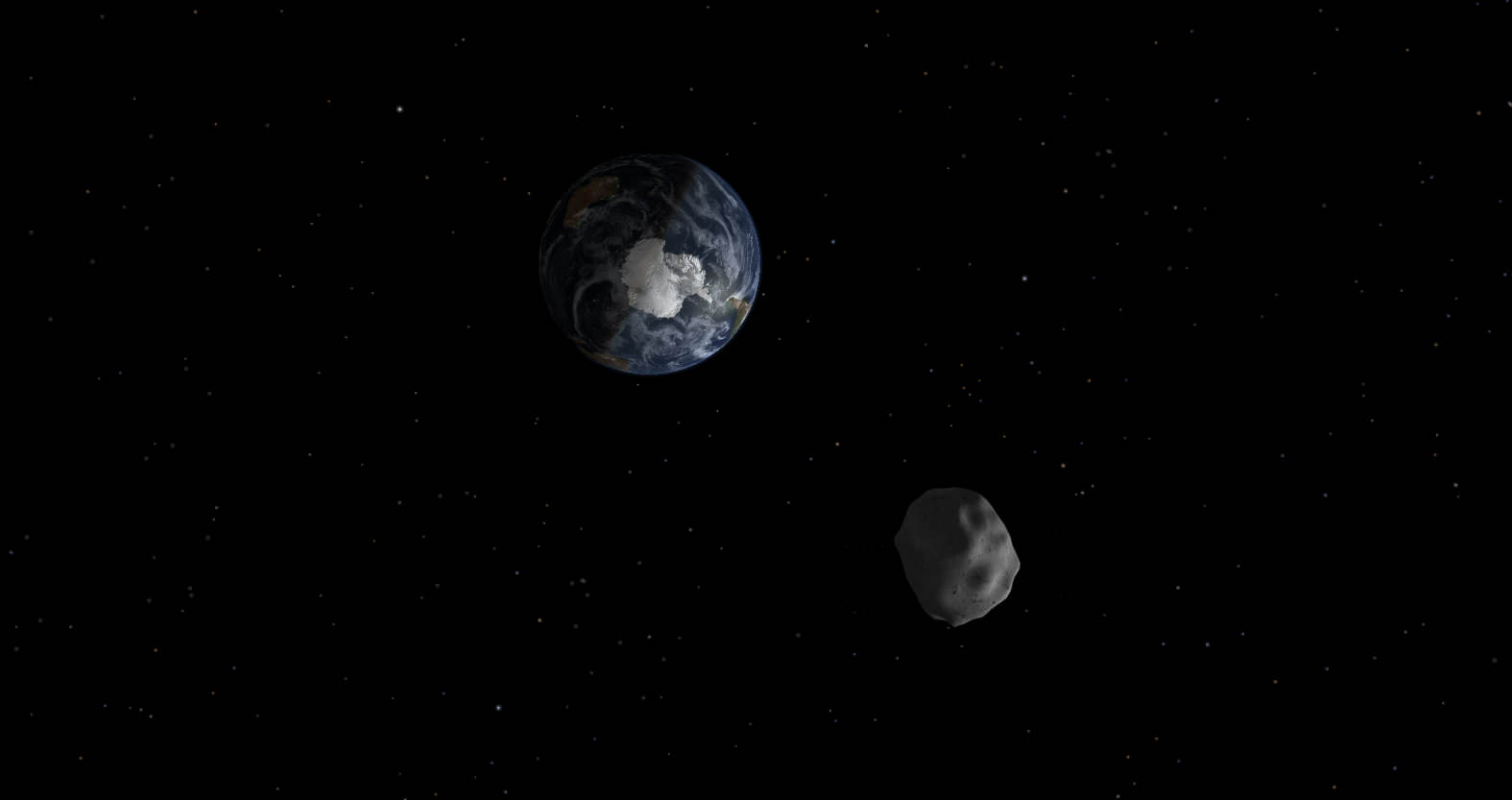

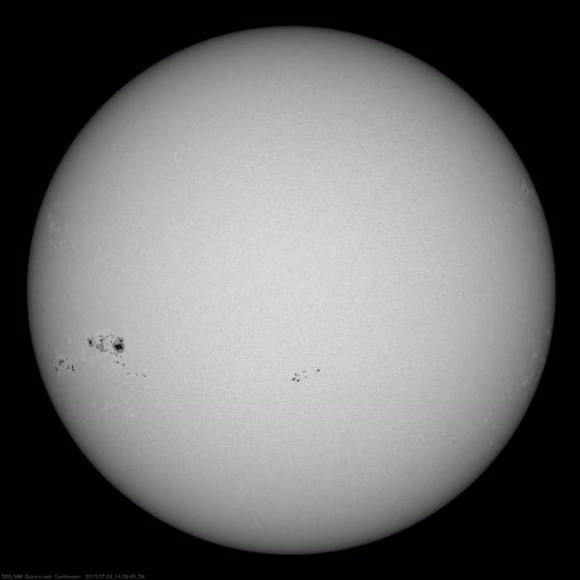

The bolide, measuring 59 feet (18 meters) across, slipped quietly into Earth’s atmosphere at 41,600 mph (18.6 kilometers per second). When the meteor hit the atmosphere, the air in front of it compressed quickly, heating up equally as quick so that it began to heat up the surface of the meteor. This created the tail of burning rock that was seen in the many videos that emerged of the event. Eventually, the space rock exploded, releasing more than 30 times the energy from the atom bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. For comparison, the ground-impacting meteor that triggered mass extinctions, including the dinosaurs, measured about 10 km (6 miles) across and released about 1 billion times the energy of the atom bomb.

Atmospheric physicist Nick Gorkavyi from Goddard Space Flight Center, who works with the Suomi satellite, had more than just a scientific interest in the event. His hometown is Chelyabinsk.

“We wanted to know if our satellite could detect the meteor dust,” said Gorkavyi, who led the study, which has been accepted for publication in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. “Indeed, we saw the formation of a new dust belt in Earth’s stratosphere, and achieved the first space-based observation of the long-term evolution of a bolide plume.”

The team said they have now made unprecedented measurements of how the dust from the meteor explosion formed a thin but cohesive and persistent stratospheric dust belt.

About 3.5 hours after the initial explosion, the Ozone Mapping Profiling Suite instrument’s Limb Profiler on the NASA-NOAA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite detected the plume high in the atmosphere at an altitude of about 40 km (25 miles), quickly moving east at about 300 km/h (190 mph).

The day after the explosion, the satellite detected the plume continuing its eastward flow in the jet and reaching the Aleutian Islands. Larger, heavier particles began to lose altitude and speed, while their smaller, lighter counterparts stayed aloft and retained speed – consistent with wind speed variations at the different altitudes.

By Feb. 19, four days after the explosion, the faster, higher portion of the plume had snaked its way entirely around the Northern Hemisphere and back to Chelyabinsk. But the plume’s evolution continued: At least three months later, a detectable belt of bolide dust persisted around the planet.

Gorkavyi and colleagues combined a series of satellite measurements with atmospheric models to simulate how the plume from the bolide explosion evolved as the stratospheric jet stream carried it around the Northern Hemisphere.

“Thirty years ago, we could only state that the plume was embedded in the stratospheric jet stream,” said Paul Newman, chief scientist for Goddard’s Atmospheric Science Lab. “Today, our models allow us to precisely trace the bolide and understand its evolution as it moves around the globe.”

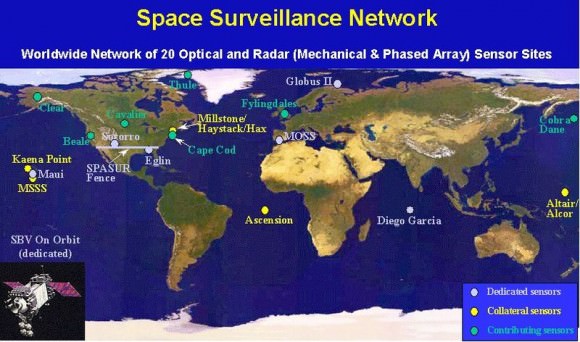

NASA says the full implications of the study remain to be seen. Scientists have estimated that every day, about 30 metric tons of small material from space encounters Earth and is suspended high in the atmosphere. Now with the satellite technology that’s capable of more precisely measuring small atmospheric particles, scientists should be able to provide better estimates of how much cosmic dust enters Earth’s atmosphere and how this debris might influence stratospheric and mesospheric clouds.

It will also provide information on how common bolide events like the Chelyabinsk explosion might be, since many might occur over oceans or unpopulated areas.

“Now in the space age, with all of this technology, we can achieve a very different level of understanding of injection and evolution of meteor dust in atmosphere,” Gorkavyi said. “Of course, the Chelyabinsk bolide is much smaller than the ‘dinosaurs killer,’ and this is good: We have the unique opportunity to safely study a potentially very dangerous type of event.”

Source: NASA