It’s unclear how the Kepler space telescope’s science operations will continue, if at all, as NASA weighs what to do with the crippled spacecraft. But the agency says not to count Kepler out yet.

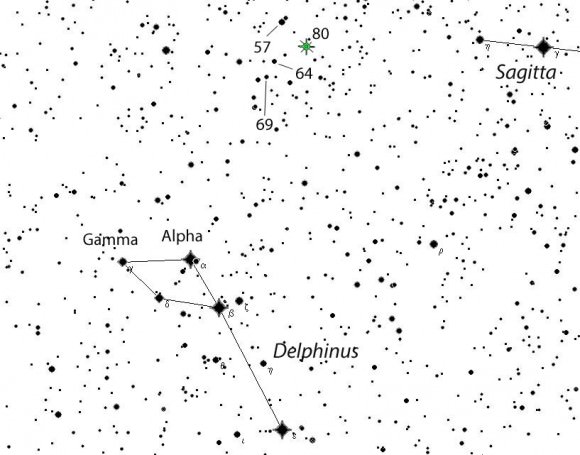

What’s known for sure is NASA cannot recover the two failed reaction wheels that stopped Kepler from doing its primary science mission, which was searching for exoplanets (with a focus on Earth-sized exoplanets) in a small area in the constellation Cygnus.

“We do not believe we can recover three-wheel operation or Kepler’s original science mission,” said Paul Hertz, NASA astrophysics division director, in a telephone press conference with reporters Thursday (Aug. 15).

But the spacecraft, which is already working years past when its prime mission ceased in 2010, is still in great shape otherwise, added Charles Sobeck, Kepler’s deputy project manager.

As such, NASA is now considering other science missions, which could be anything from searching for asteroids to a technique called microlensing, which could show Jupiter-sized planets around other stars with the spacecraft’s more limited pointed ability. More information should be available in the fall on these points, once Kepler’s team reviews some white papers with science proposals.

There are limiting factors. The first is the health of the spacecraft, but it is so far listed as good (except for the two damaged reaction wheels). While radiation can degrade components over time, and a stray micrometeorid could (as a small chance) cause damage on the spacecraft, right now Kepler is able to work on something new, Sobeck said.

“We have it in a point rest state right now,” Sobeck said, referring to a state where the spacecraft uses as little fuel as possible. This will extend the fuel “budget” for years, although Sobeck was unable to say just how many years yet.

Another concern is NASA’s limited budget, which (like other government departments) has undergone sequestration and other measures as the U.S. government grapples with its debt. Kepler has an estimated $18 million budget in fiscal 2013, agency officials said, adding they would need to weigh any future science mission against those of other projects being done by the agency.

The public drama began on May 15, when NASA announced that a second of Kepler’s four reaction wheels — devices that keep the telescope pointed in the right direction — had failed.

“We need three wheels in service to give us the pointing precision to enable us to find planets,” said Bill Borucki, Kepler principal investigator, during a press briefing that day. “Without three wheels, it is unclear whether we could continue to do anything on that order.”

Around the same time, Scott Hubbard — a consulting professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford’s School of Engineering — wrote an online Q&A about Kepler’s recovery process. He emphasized the potential loss, although sad, is not devastating to the science.

“The science returns of the Kepler mission have been staggering and have changed our view of the universe, in that we now think there are planets just about everywhere,” he wrote.

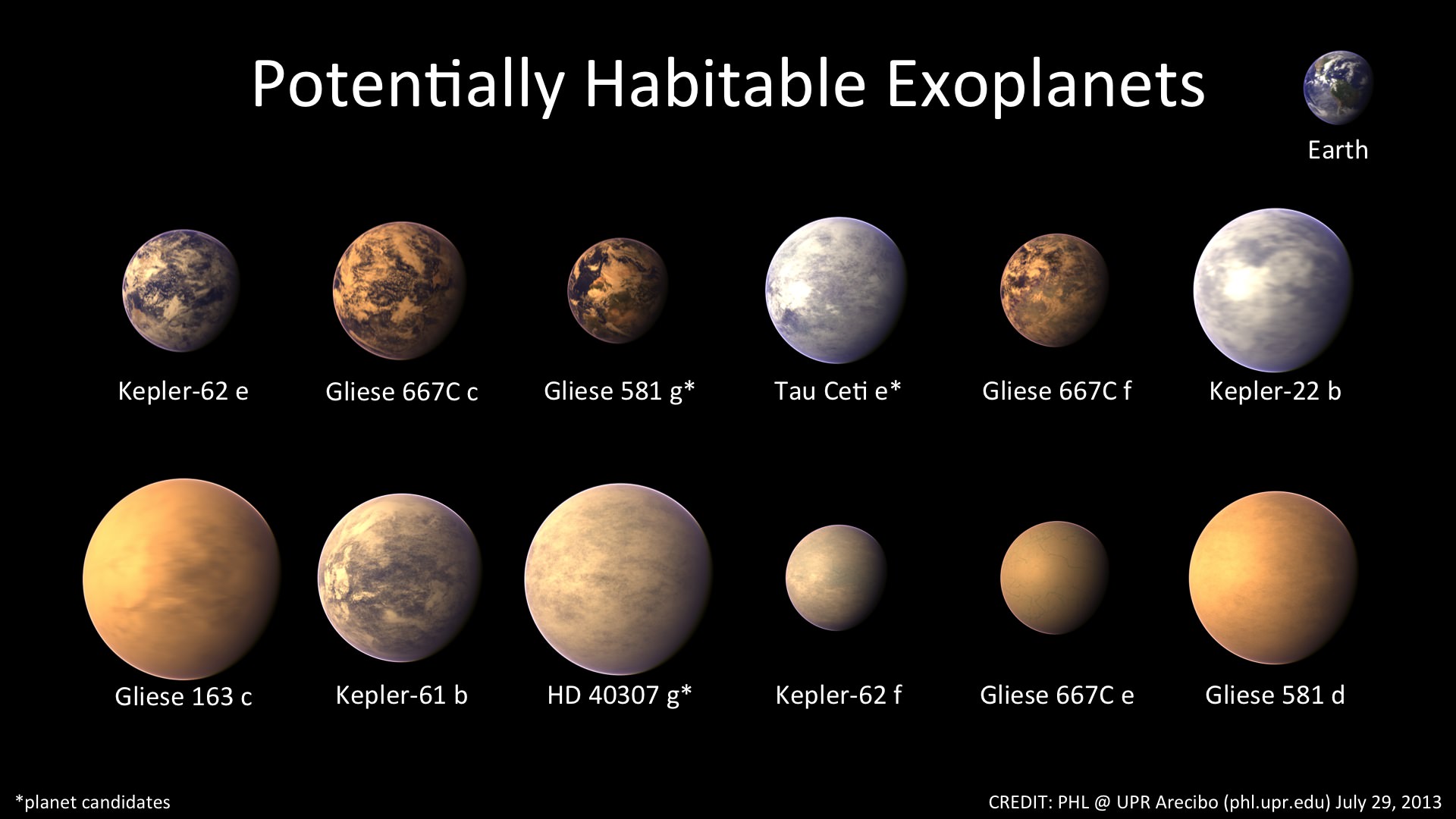

“It will be very sad if it can’t go on any longer, but the taxpayers did get their money’s worth. Kepler has, so far, detected more than 2,700 candidate exoplanets orbiting distant stars, including many Earth-size planets that are within their star’s habitable zone, where water could exist in liquid form.” (You can read about some of Kepler’s more unusual finds here.)

NASA made several attempts to resurrect the wheels. On July 18, team members tested reaction wheel four, which spun in a counterclockwise direction but would not budge in the clockwise direction. Four days later, a test with reaction wheel two showed it moving well to the test commands in both directions.

“Over the next two weeks, engineers will review the data from these tests and consider what steps to take next,” mission manager Roger Hunter said. “Although both wheels have shown motion, the friction levels will be critical in future considerations. The details of the wheel friction are under analysis.”

Mission managers successfully spun reaction wheel 4 in both directions on July 25, an Aug. 2 update said. While warning that friction could affect the usability of the wheels in the long term, the team expressed optimism as more tests continued.

“With the demonstration that both wheels will still move, and the measurement of their friction levels, the functional testing of the reaction wheels is now complete,” Hunter wrote in the update, the last one to go out before Thursday’s press conference.”The next step will be a system-level performance test to see if the wheels can adequately control spacecraft pointing.”

That was expected to begin Aug. 8. You can read more technical details of the tests here. Those tests, however, showed that the friction built up beyond what the spacecraft could handle. Kepler entered safe mode, it was recovered, and it is now essentially in standby awaiting more instructions.

Meanwhile, probing the data Kepler produced thus far is still revealing new planetary candidates. The current count is now 3,548 — an increase from the approximately 2,700 quoted in May — even though Kepler was sidelined in the intervening time.

There’s also a follow-up spacecraft planned: the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which is expected to start around 2017 or 2018. It will look for alien planets in the brightest and closest stars in the entire sky, in locations that are (in relative terms) close to Earth.