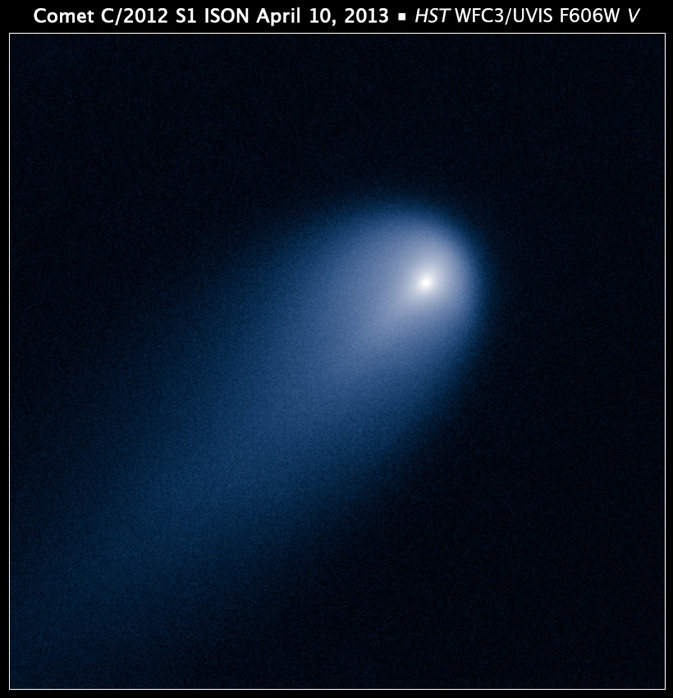

A press release out yesterday about a recent paper on Comet ISON has caused a mild uproar across the astronomy-minded social media outlets and some websites. The article issued from the Physics & Astrophysics Computation Group (FACOM) at the University of Antioquia in Medellin, Colombia is titled “Comet Of The Century? Not Yet! Comet C/2012 S1 ISON Has Fizzled Completely And May Disintegrate At Or Before Reaching Perihelion.”

The article had professional astronomers and comet enthusiasts alike shaking their heads in disbelief.

For one, any current determination of ISON’s ultimate fate when it gets close to the Sun later this year is speculation at best, (as is the case with almost any other sun-grazing comet) and since no one on planet Earth has seen ISON since it entered the Sun’s glare in June, there is absolutely no way to determine the comet’s current state, either. The almost unanimous shout from the astronomy internets was “Please! We just have to wait and see what happens with ISON.”

But the press release also had this journalist (and others) wondering if Ferrin’s views were taken out of context for the sake of a dramatic press release.

For example, nowhere in his paper does Ferrin say that Comet ISON has “fizzled,” (nor is there a direct quote in the press release with that word) and he does make it clear in his paper that his information about the comet is preliminary. However, the press release seemingly infers there was new data and that the comet is nothing short of dead.

But in an email from Ferrin, in response to an inquiry from Universe Today, Ferrin stands by the press release, as well as his opinion that Comet ISON “does not have a bright future.”

“The term ‘fizzled completely’ is not a scientific term so it should not go into a scientific paper,” Ferrin said. “However it reflects reality with the information we have.”

His paper (a full 51-pages) was posted to arXiv on June 20, 2013, and has been submitted to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, still undergoing peer review. The paper is based on data available up to the last good observing date in late-May, 2013, and Ferrin said in his email to Universe Today that up to that point “there is no evidence of brightening whatsoever. I doubt that anybody has seen that brightening.”

Ferrin, a well-known cometary scientist, concurred that the comet’s current state is unknown because it has entered the Sun’s glare but when last seen it had not brightened at all, adding in his email that “the fact that the comet was in a standstill situation makes it very improbable of becoming as bright as the Moon.”

As astronomer Karl Battams said, that last statement is hardly breaking news. Battams is an astrophysicist and computational scientist based at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington DC, and he has operated the NASA-funded Sungrazing Comets Project since 2003. He’s also part of the Comet ISON Observing Campaign a massive, global observing campaign for ISON for both professional and amateur astronomers.

“Few serious astronomers and cometary scientists have ever felt ISON would be ‘brighter than the full Moon,’ Battams told Universe Today. “That’s entirely the media’s term, and we’ve been saying this for months, that none of us in the CIOC foresee ISON getting that bright, and never have done so. So we’re side-by-side with Ferrin in that respect.”

But Battams has some issues with both the paper and the press release.

“The paper is a mixture of reporting facts, and performing extrapolations and modeling based on certain theories and models, some of which are more developed than others,” Battams told Universe Today via email. “Ferrin’s analysis is based on data taken up until around the end of May, but the article misleads by implying that Ferrin has used recent data, which he hasn’t, as there is none. He has simply applied his own methods, model and analysis to the same data that we all have.”

Battams said he can’t comment on the quality of those models, but said Ferrin’s conclusions are broad enough that they don’t seem entirely out of line with what everyone else is saying about the comet – that there is a range of possible outcomes: Comet ISON might fizzle before it gets here or it might disintegrate before, or at perihelion, but it also might still brighten up.

“There’s really no new conclusion here — just a different methods that leads to the same conclusion,” Battams said.

In the paper, Ferrin reaches some of his conclusions comparing ISON to Comet Honig (2002 O4), the brightness of which he says “was in a standstill for 52 days after which it disintegrated.”

Battams said astronomers have to be cautious in comparing ISON to another comet – especially comparing it to Honig, which was not a sungrazer and shared little in common with ISON other than also being a comet.

“ISON is both a Sungrazer, and dynamically new from the Oort Cloud,” he said. “We have no modern record of such an object (see this article about ISON’s uniqueness) so we must exercise a little more caution than usual when comparing it to other comets. The last “major” sungrazer we had was Lovejoy in 2011, and for an object likely much smaller than ISON, it put on a pretty good show.”

Another astronomer with the CIOC, Matthew Knight from the Lowell Observatory also took issue with the comparison.

“Comparing ISON to 2002 O4 Honig ignores the fact that they were in very different places in the solar system,” Knight said via email, replying to an inquiry from Universe Today regarding Ferrin’s paper. “Honig began flattening out at 1.26 AU as it approached perihelion… ISON being flat at 4-5 AU is a completely different physical realm, since water and other volatiles are not expected to be very active yet.”

Knight also differed with Ferrin’s opinion that ISON’s peculiar non-brightening behavior when last seen “could possibly be explained if the comet were water deficient, or if a surface layer of rock or non-volatile silicate dust were quenching the sublimation to space.”

“This ignores the fact that water isn’t expected to be driving activity from January through June because ISON was still beyond the “frost line” (somewhere between 2.5 and 3 AU) beyond which water doesn’t sublimate efficiently because it is too cold,” Knight said. “It is only when a comet passes inside the frost line that water-driven activity is expected to ramp up…. I fully expect that once it passes inside the frost line, activity will pick up again. We should know as soon as it reemerges from behind the Sun in late August/early September.”

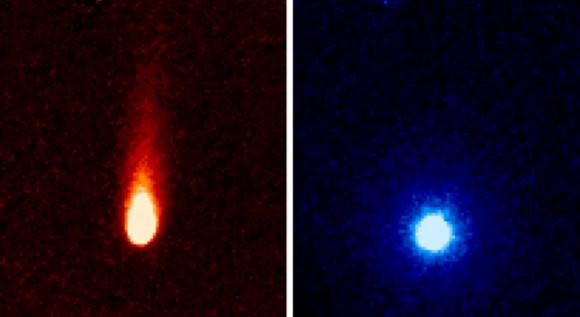

As to whether ISON has ‘fizzled’ both Battams and Knight noted that the recently released Spitzer observations from June 13 (and released on July 24 – well after Ferrin’s paper was published) showed the comet was ‘fizzy,’ not fizzled, as it was actively spewing out carbon dioxide and dust.

In the end, no matter what any current paper or press release says about Comet ISON, nothing will be known for sure until we see ISON again, and until it gets closer to the Sun. It will pass about 1.2 million km (724,000 miles) from the Sun at closest approach on November 28, 2013.

For now, everyone needs to wait and watch what happens and end the speculation.

However, as noted by Daniel Fischer on Twitter, the reaction caused by the press release related to Ferrin’s paper has been, unfortunately, “dramatic.”

@SungrazerComets Dramatic is the *reaction* … did a Twitter "ISON" search -> within one hour 'mood' switched from "super comet" to "pfft".

— Daniel Fischer (@cosmos4u) July 30, 2013

Any hype either way — whether it is calling this the Comet of the Century or a comet that has fizzled — only does a disservice to astronomy, and gives the general public the wrong impression of both the comet and science’s ability to study and predict astronomical phenomenon.