We all love space here and we’re sure, given that thousands of people applied for a one-way trip to Mars, that at least some of you want to spend a long time in a spacecraft. But have you thought about the bacteria that will be going along with you?

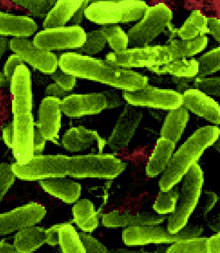

If you don’t feel too squirmy to read on, understand this: one type of bacteria grown aboard two shuttle missions ended up being bigger and thicker than control colonies on Earth, new NASA research shows.

Two astronaut crews aboard space shuttle Atlantis grew colonies of bacteria (more properly speaking, biofilms) on behalf of researchers on Earth. Most biofilms are harmless, but a small number could be associated with disease.

Biofilms were all over the Mir space station, and managing them is also a “challenge” (according to NASA) on the International Space Station. Well, here’s how they appeared in this study:

“The space-grown communities of bacteria, called biofilms, formed a ‘column-and-canopy’ structure not previously observed on Earth,” NASA stated. “Biofilms grown during spaceflight had a greater number of live cells, more biomass, and were thicker than control biofilms grown under normal gravity conditions.”

The type of microorganism examined was Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which was grown for three days each on STS-132 and STS-135 in artificial urine. That was chosen because, a press release stated, “it is a physiologically relevant environment for the study of biofilms formed both inside and outside the human body, and due to the importance of waste and water recycling systems to long-term spaceflight.”

Each shuttle mission had several vials of this … stuff … in which to introduce the bacteria in orbit. The viles included cellulose membranes on which the bacteria could grow. Researchers also tested bacteria growth on Earth with similar vials. Then, all the samples were rounded up in the lab after the shuttle missions where the biofilms’ thickness, number of cells and volume was examined, as well as their structure.

This is still early-stage work, of course, requiring follow-up studies to find out how the low-gravity environment affects these microorganisms’ growth, according to lead researcher Cynthia Collins from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Metabolism and virulence are what the scientists are hoping to learn more about in the future.

“Before we start sending astronauts to Mars or embarking on other long-term spaceflight missions, we need to be as certain as possible that we have eliminated or significantly reduced the risk that biofilms pose to the human crew and their equipment,” stated Collins, an assistant professor in the department of chemical and biological engineering.

While this research has more immediate implications for astronaut health, the researchers added that better understanding the biofilms could lead to better treatment and prevention for Earth diseases.

“Examining the effects of spaceflight on biofilm formation can provide new insights into how different factors, such as gravity, fluid dynamics, and nutrient availability affect biofilm formation on Earth. Additionally, the research findings could one day help inform new, innovative approaches for curbing the spread of infections in hospitals,” a NASA press release stated.

If you’re not feeling too itchy by now, you can read the entire study in an April issue of PLOS ONE.

Credit: NASA