Do the aurorae makes sounds? That’s been a subject of discussion — and contention — among people who watch the sky. While most of us will never hear the aurora borealis directly, there’s help out there in the form of a little handheld radio. It’s called a VLF receiver and guarantees you an earful the next time the aurora erupts.

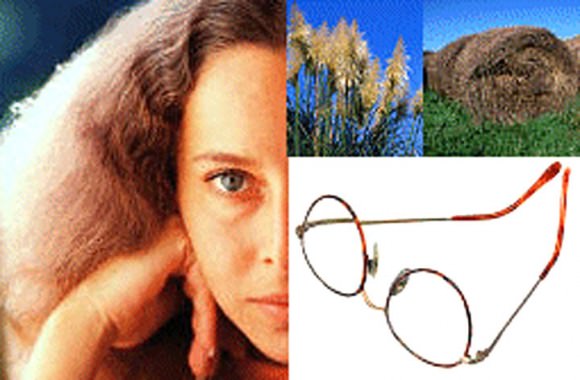

Despite seeing hundreds of northern light displays ranging from mild to wild, I’ve yet to actually hear what some describe as crackles and hissing noises. There is some evidence that electrophonic transduction can convert otherwise very low frequency (VLF) radio waves given off by the aurora into sound waves through nearby conductors. Wire-framed eyeglasses, grass and even hair can act as transducers to convert radio energy into low-frequency electric currents that can vibrate an object into producing sound. Similar ‘fizzing’ sounds have been recorded by meteor watchers that may happen the same way.

Imagination may be another reason some folks people hear auroras. Things that move often make sounds. A spectacular display of moving lights overhead can trick your brain into serving up an appropriate soundtrack. Given that the aurora is never closer to the ground than 50 miles, the air is far too thin at this altitude to transmit any weak sound waves that might be produced down to your ears.

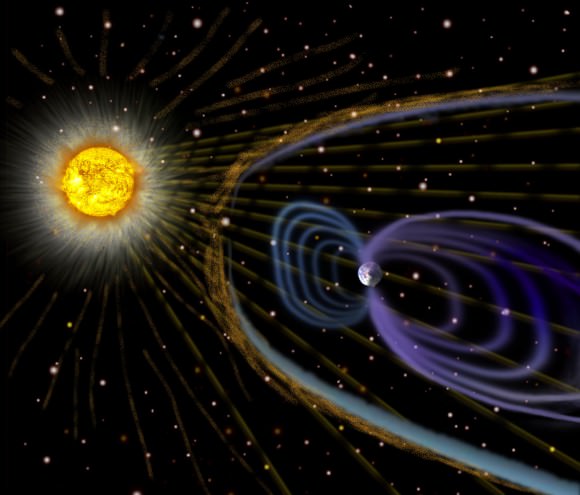

If you’re like me and hard of auroral hearing, a small VLF (very low frequency) radio receiver will do the job nicely. This handheld device converts very low frequency radio waves produced from the interaction of the solar electrons and protons with the Earth’s magnetic field into sounds you can listen to with a pair of headphones.

We’re used to waves of light which are very, very short, measuring in the millionths of an inch long. The pigments in our retinas convert these waves into visible images of the world around us. Radio waves given off by auroras and other forms of natural ‘Earth energy’ like lightning range from 19 to 1,800 miles long or longer. To bring them within range of human hearing we need a radio receiver. I fire up a little unit called a WR-3 I purchased back in the mid-1990s. The components are housed in a small metal box with a whip antenna and powered by a 9-volt battery. The on-off switch also controls the volume. Plug in a set of headphones and you’re ready to listen. That’s all there is to it.

The receiver picks up lots of things besides aurora including a big ‘unnatural’ hum from alternating or AC current in power lines and home appliances. Turn one on in your house and you’ll immediately hear a loud, continuous buzz in the headphones. You’ll need to be at least a quarter mile from any of those sources in order to hear the more subtle music of the planet.

I drive out to a open ‘radio quiet’ rural area, turn on the switch and raise the antenna to the sky. Don’t stand under any trees either. They’re great absorbers of the low frequency radio energy you’re trying to detect. What will you hear? Read on and click the links to hear the sound files.

* Sferics. The first thing will be the pops, crackles and sizzles of distant lightning called sferics which are similar to the crackles on an AM car radio during a thunderstorm.

* Tweeks. Lightning gives off lots of energy in the long end of the radio spectrum. When that energy gets ducted through the upper layers of Earth’s atmosphere called the ionosphere over distances of several thousand miles, it emits another type of sound called ‘tweeks‘. These remind me of Star Wars lasers or dripping water. Flurries of tweeks have an almost musical quality like someone plucking the strings of a piano.

* Whistlers and Whistler Clusters. When those same lightning radio waves enter Earth’s magnetosphere and interact with the particles there, they can cycle back and forth between the north and south geomagnetic poles traveling tens of thousands of miles to create whistlers. Talk about an eerie, futuristic sound. After their long journey, the higher frequency waves arrive before those of lower frequency causing the sound to spread out in a series of long, descending tones. The sound may also take you back to those old World War II movies when bombs whistled through the air after dropping from the hatch of a B-17. Tweeks are very brief; whistlers last anywhere from 1/2 to 4 seconds or longer.

* Dawn Chorus. Sometimes you’ll hear dozens of whistlers, one after the other. When conditions are right, a VLF receiver can pick up disturbances in Earth’s magnetic bubble spawned by auroras called ‘chorus‘ or ‘dawn chorus’. Talk about strange. Who would have guessed that solar electrons spiraling along Earth’s magnetic field lines would intone the ardor of frogs or a chorus of birds at dawn? And yet, there you have it.

* More Dawn Chorus: On a good night, and especially when the northern lights are out, it’s a magnetospheric symphony. Thunderstorms thousands of miles away provide a bounty of crackles and tweeks with occasional whistlers. Listen closely and you might even hear the froggy voice of the aurora rising and falling with a rhythm reminiscent of breathing.

If you’re interested in listening to VLF and in particular the aurora, basic receivers are available through the two online sites below. I’ve only used the WR-3 and can’t speak for the others, but they all run between $110-135. One word of warning if you purchase – don’t use one when there’s a lightning storm nearby. Holding a metal aerial under a thundercloud is not recommended!

* WR-3 VLF receiver from Stephen McGreevy

* North Country Radio ELF Earth Receiver

More on natural radio can be found HERE. Things to keep in mind when considering a purchase are whether you have access to an open area 1/2 mile from a power line and away from homes. You’ll also need patience. Many nights you’ll only hear lightning crackles from distant storms thousands of miles away peppered by the occasional ping of a tweet. Whistlers may not appear for weeks at a time and then one night, you’ll hear them by the hundreds. But if you regularly watch the sky, it’s so easy to take the radio along and ‘give a listen’ for some of the most curious sounds you’ll ever hear. How astonishing it is to sense our planet’s magnetosphere through sound. Consider it one more way to be in touch with the home planet.

For more on natural radio including additional sound files I invite you to check out Stephen P. McGreevy’s site.