It’s a bird, it’s a plane it’s…

OK, it’s a bad gag, I know. But the movie Man of Steel isn’t the only thing that’s “super” about June this year. The closest full Moon of 2013 occurs on June 23, when it will be 356,991 kilometres from Earth, within 600 kilometres of its closest possible approach. When the Moon is closest to Earth in its orbit, it also appears just a bit larger in the sky. But that’s if you’re really paying attention, however!

Some claims circulating on the Internet tend to exaggerate how large the Moon will actually appear. And as for the assertions that the Moon will look bright purple or blue on June 23, that’s just not true. As seems to happen every year, the term “supermoon” has once again reared its (ugly?) head across ye ole Internet. Hey, it’s a teachable moment, a good time to look at where the term came from, and examine the wonderful and wacky motion of our Moon.

I’ll let you in on a small secret. Most astronomers, both of the professional and backyard variety, dislike the informal term “supermoon”. It arose in astrology circles over the past few decades, and like the term “Blue Moon” seems to have found new life on the Internet. A better term from the annuals of astronomy for the near-coincidence of the closest approach of the Full Moon would be Perigee Full Moon. And if you really want to be archaic, Proxigean Moon is also acceptable.

On June 23, 2013, the Moon will be full at 7:32 AM EDT/ 11:32 UT, only 20 minutes after it reaches perigee, or its closest point to Earth in its orbit.

You can see the change in apparent size of the Moon (along with a rocking motion of the Moon known as nutation and libration) in this video from the Goddard Space Flight Center’s Scientific Visualization Studio. You can also see full animations for Moon phases and libration for 2013 from the northern hemisphere and southern hemisphere.

And all perigees are not created equal, either. Remember, a Full Moon is an instant in time when the Moon’s longitude along the ecliptic is equal to 180 degrees. Thus, the Full Moon rises (unless you’re reading this from high polar latitudes!) opposite as the Sun sets. Perigee also oscillates over a value of just over 2 Earth radii (14,000 km) from 356,400 to 370,400 km. And while that seems like a lot, remember that the average distance to the Moon is about 60 earth radii, or 385,000 km distant.

Astronomers yearn for kryptonite for the supermoon. The Moon passes nearly as close every 27.55 days, which is the time that it takes to go from one perigee to another, known as an anomalistic month. This is not quite two days shorter than the more familiar synodic month of 29.53 days, the amount of time it takes the Moon to return to similar phase (i.e. New to New, Full to Full, etc).

This offset may not sound like much, but 2 days can add up. Thus, in six months time, we’ll have perigee near New phase and the smallest apogee Full Moon of the year, falling in 2013 on December 19th. Think of the synodic and anomalistic periods like a set of interlocking waves, cycling and syncing every 6-7 months.

You can even see this effect looking a table of supermoons for the next decade;

|

Super Moons for the Remainder of the Decade 2013-2020. |

|||||

|

Year |

Date |

Perigee Time |

Perigee Distance |

Time from Full |

Notes |

|

2013 |

June 23 |

11:11UT |

356,989km |

< 1 hour |

|

|

2013 |

July 21 |

20:28UT |

358,401km |

-21 hours |

|

|

2014 |

July 13 |

8:28UT |

358,285km |

+21 hours |

|

|

2014 |

August 10 |

17:44UT |

356,896km |

< 1 hour |

|

|

2014 |

September 8 |

3:30UT |

358,387km |

-22 hours |

|

|

2015 |

August 30 |

15:25UT |

358,288km |

+20 hours | |

|

2015 |

September 28 |

1:47UT |

356,876km |

-1 hour |

Eclipse |

|

2015 |

October 26 |

13:00UT |

358,463km |

-23 hours |

|

|

2016 |

October 16 |

23:37UT |

357,859km |

+19 hours |

Farthest |

|

2016 |

November 14 |

11:24UT |

356,511km |

-2 hours |

Closest |

|

2017 |

December 4 |

8:43UT |

357,495km |

+16 hours |

|

|

2018 |

January 1 |

21:56UT |

356,565km |

-4 hours |

|

|

2019 |

January 21 |

19:59UT |

357,344km |

+14 hours |

Eclipse |

|

2019 |

February 19 |

9:07UT |

356,761km |

-6 hours |

|

|

2020 |

March 10 |

6:34UT |

357,122km |

+12 hours |

|

|

2020 |

April 7 |

18:10UT |

356,908km |

-8 hours |

|

| Sources: The fourmilab Lunar Perigee & Apogee Calculator & NASA’s Eclipse Website 2011-2020.Note: For the sake of this discussion, a supermoon is defined here as a Full Moon occurring within 24 hours of perigee. Other (often arbitrary) definitions exist! | |||||

Note that the supermoon slowly slides through our modern Gregorian calendar by roughly a month a year.

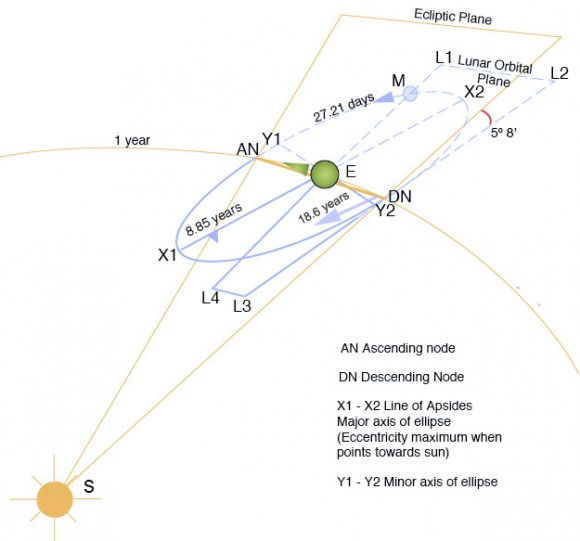

In fact, the line of apsides (an imaginary line drawn bisecting the Moon’s orbit from perigee to apogee) completes one revolution every 8.85 years. Thus, in 2022, the supermoon will once again occur in the June-July timeframe.

To understand why this is, we have to look at another unique feature of the Moon’s orbit. Unlike most satellites, the Moon’s orbit isn’t fixed in relation to its primaries’ (in this case the Earth’s) equator. Earth rotational pole is tilted 23.4 degrees in relation to the plane of its orbit (known as the ecliptic), and the Moon’s orbit is set at an inclination of 5.1 degrees relative to the ecliptic. In this sense, the Earth-Moon system behaves like a binary planet, revolving around a fixed barycenter.

The two points where the Moon’s path intersects the ecliptic are known as the ascending and descending nodes. These move around the ecliptic as well, lining up (known as a syzygy) during two seasons a year to cause lunar and solar eclipses.

But our friend the line of apsides is being dragged backwards relative to the motion of the nodes, largely by the influence of our Sun. Not only does this cause the supermoons to shift through the calendar, but the Moon can also ride ‘high’ with a declination of around +/-28 degrees relative to the celestial equator once every 19 years, as happened in 2006 and will occur again in 2025.

Falling only two days after the solstice, this month’s supermoon is also near where the Sun will be in December and thus will also be the most southerly Full Moon of 2013. Visually, the Full Moon only varies 14% in apparent diameter from 34.1’ (perigee) to 29.3’ (apogee).

A fun experiment is to photograph the perigee Moon this month and then take an image with the same setup six months later when the Full Moon is near apogee. Another feat of visual athletics would be to attempt to visually judge the Full Moons throughout a given year. Which one do you think is largest & smallest? Can you discern the difference with the naked eye? Of course, you’d also have to somehow manage to insulate yourself from all the supermoon hype!

Many folks also fall prey to the rising “Moon Illusion.” The Moon isn’t visually any bigger on the horizon than overhead. In fact, you’re about one Earth radii closer to the Moon when it’s at the zenith than on the horizon. This phenomenon is a psychological variant of the Ponzo illusion.

Here are some of the things that even a supermoon can’t do, but we’ve actually heard claims for:

– Be physically larger. You’re just seeing the regular-sized Moon, a tiny bit closer.

– Cause Earthquakes. Yes, we can expect higher-than-normal Proxigean ocean tides, and there are measurable land tides that are influenced by the Moon, but no discernible link between the Moon and earthquakes exists. And yes, we know of the 2003 Taiwanese study that suggested a weak statistical correlation. And predicting an Earthquake after it has occurred, (as happened after the 2011 New Zealand quake) isn’t really forecasting, but a skeptical fallacy known as retrofitting.

– Influence human behavior. Well, maybe the 2013 Full Moon will make some deep sky imagers pack it in on Sunday night. Lunar lore is full of such anecdotes as more babies are born on Full Moon nights, crime increases, etc. This is an example the gambler’s fallacy, a matter of counting the hits but not the misses. There’s even an old wives tale that pregnancy can be induced by sleeping in the light of a Full Moon. Yes, we too can think of more likely explanations…

– Spark a zombie apocalypse. Any would-be zombies sighted (Rob Zombie included) during the supermoon are merely coincidental.

Do get out and enjoy the extra illumination provided by this and any other Full Moon, super or otherwise. Also, be thankful that we’ve got a large nearby satellite to give our species a great lesson in celestial mechanics 101!