Today we residents of planet Earth meet up with a meteor stream with a strange and bizarre past.

The Lyrid meteors occur annually right around April 21st to the 23rd. A moderate meteor shower, observers in the northern hemisphere can expect to see about 20 meteors in the early morning hours under optimal conditions. Such has been the case for recent years past, and this year’s presence of a waxing gibbous Moon has lowered prospects for this April shower considerably in 2013.

But this has not always been the case with this meteor stream. In fact, we have records of the Lyrids stretching back over the past 2,600 years, farther back than any other meteor shower documented.

The earliest account of this shower comes from a record made by Chinese astronomers in 687 BC, stating that “at midnight, stars dropped down like rain.” Keep in mind that this now famous assertion that is generally attributed to the Lyrids was made by mathematician Johann Gottfried Galle in 1867. It was Galle along with Edmond Weiss who noticed the link between the Lyrids and Comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher discovered six years earlier.

Comet Thatcher was discovered on April 5th, 15 days before it reached perihelion about a third of an astronomical unit (A.U.) from the Earth. Comet Thatcher a periodic comet on a 415 year long orbital period.

But in the early to mid-19th century, the very idea that meteor showers were linked to comets or even non-atmospheric phenomena was still hotly contested.

One singular event more than any other triggered this realization. The Leonid meteor storm of 1833 in the early morning hours of November 13th was a stunning and terrifying spectacle for residents of the U.S eastern seaboard. This shower produces mighty outbursts, often topping a Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) of over a 1,000 once every 33 to 34 years. I witnessed a fine outburst of the Leonids from Kuwait in 1998, and we may be in for a repeat performance from this shower around 2032 or 2033.

There is substantial evidence that the Lyrids may also do the same at an undetermined interval. On April 20th 1803, one of the most famous accounts of a “Lyrid meteor storm” was observed up and down the United States east coast. For example, one letter to the Virginia Gazette states;

“From one until three, those starry meteors seemed to fall from every point in the sky heavens, in such numbers as to resemble a shower of sky rockets.”

Another account published in the Raleigh, North Carolina Register states that:

“The whole hemisphere as far as the extension of the horizon seemed illuminated; the meteors kept no particular direction but appeared to move in every way.”

A study of the 1803 Lyrid outburst by W.J. Fisher cites over a dozen accounts of the event and is a fascinating read. Viewers were also primed for the event by the dramatic Leonid storm of 1799 four years earlier.

Interestingly, the Moon was only one day from New phase on the night of the 1803 Lyrids. Prime meteor watching conditions.

An unrelated meteorite fall would also occur four years later over Weston, Connecticut on December 14th, 1807 as recounted by Kathryn Prince in A Professor, A President, and a Meteor. These events would place Yankee politics at odds with the origin of meteors and rocks from the sky.

An apocryphal quote is often attributed to President Thomas Jefferson that highlights the controversy of the day, saying that “I would more easily believe that two Yankee professors would lie than that stones would fall from heaven.”

While both are of cosmogenous origin, no meteorite fall has ever been linked to a meteor shower, which is spawned by dust debris from comets. For example, many in the media erroneously speculated that the Sutter’s Mill meteorite that fell to Earth on the morning of April 22nd, 2012 was in fact a Lyrid meteor.

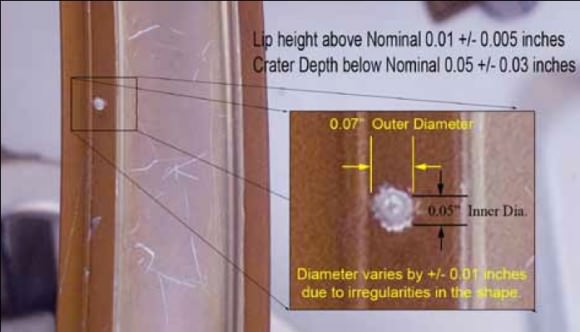

But a Lyrid may be implicated in another unusual 19th century observation. On April 24th 1874, a professor Scharfarik of Prague, Czechoslovakia was observing the daytime First Quarter Moon with his 4” refractor. The good professor was surprised by an “Apparition on the disc of the Moon of a dazzling white star,” which was “quite sharp and without a perceptible diameter.” Possible suspects are a telescopic meteor moving towards or along the observers’ line of sight or perhaps a Lyrid impacting the dark limb of the Moon.

Moving into the 20th century, rates for the Lyrids have stayed in the ZHR=20 range, with notable peaks of 100+ per hour noted by Japanese observers in 1922 and 100 per hour noted by U.S. observers in 1982.

It should also be noted that another less understood shower radiates from the constellation Lyra in mid-June. First noted Stan Dvorak while hiking in the San Bernardino Mountains in 1966, the June Lyrids produce about 8-10 meteors per hour from June 10 to the 21st. The source of this newly discovered shower is thought to be Comet C/1915 C1 Mellish.

A June Lyrid may have even made its way into modern fiction. As recounted in a July 2004 issue of Sky & Telescope, researchers Marilynn & Donald Olson note the following line from James Joyce’s Ulysses:

“A star, precipitated with great apparent velocity across the firmament from Vega in the Lyre above the zenith.”

Joyce seems to be describing a June Lyrid decades before the shower was officially recognized. The constellation Lyra rides high in the early morning sky for mid-northern latitudes in the early summer months.

All interesting concepts to ponder as we keep an early morning vigil for the Lyrids this week. Could there be more Lyrid storms in the far off future, as Comet Thatcher reaches perihelion once again in the late 23rd century? Could more historical clues of the untold history of this and other showers be awaiting discovery?

Somewhat closer to us in time and space, Paul Wiegert of the University of Ontario has also recently speculated that Comet 2012 S1 ISON may provoke a meteor shower on January 12th, 2014. Regardless of whether ISON turns out to be the “Comet of the Century,” this could be one to watch out for!