Will the comet that’s been billed as the “the comet of the century” live up to expectations? Astronomers are getting a better idea of the makeup of Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON), and have now taken a look at it with the Swift satellite. They’ve been able to make initial estimates of the size of the comet’s nucleus.

“Comet ISON has the potential to be among the brightest comets of the last 50 years, which gives us a rare opportunity to observe its changes in great detail and over an extended period,” said Lead Investigator Dennis Bodewits, an astronomer at the University of Maryland College Park (UMCP.)

Bodewits and his team used Swift’s Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT) to make initial estimates of the comet’s water and dust production, and then infer the size of its icy nucleus. They observed the comet on January 30 and then again late in February.

The January observations revealed that ISON was shedding about 112,000 pounds (51,000 kg) of dust, or about two-thirds the mass of an unfueled space shuttle, every minute. By contrast, the comet was producing only about 130 pounds (60 kg) of water every minute, or about four times the amount flowing out of a residential sprinkler system.

Similar levels of activity were observed in February, and the team plans additional UVOT observations.

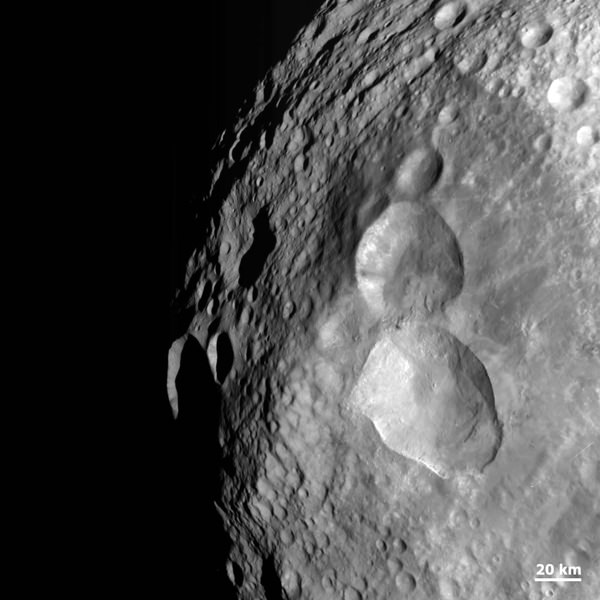

Using the water and dust production, the astronomers estimated the size of ISON’s icy nucleus as roughly 3 miles (5 km) across, a typical size for a comet. This assumes that only the fraction of the surface most directly exposed to the Sun, about 10 percent of the total, is actively producing jets. The astronomers noted that these rates of water and dust production are relatively uncertain because of the comet’s faintness.

“The mismatch we detect between the amount of dust and water produced tells us that ISON’s water sublimation is not yet powering its jets because the comet is still too far from the Sun,” Bodewits said. “Other more volatile materials, such as carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide ice, evaporate at greater distances and are now fueling ISON’s activity.”

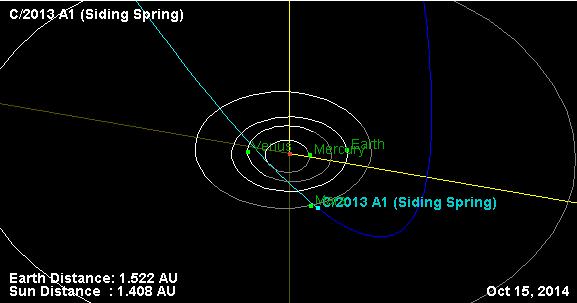

At the time, the comet was 375 million miles (604 million km) from Earth and 460 million miles (740 million km) from the Sun. ISON was at magnitude 15.7 on the astronomical brightness scale, or about 5,000 times fainter than the threshold of human vision.

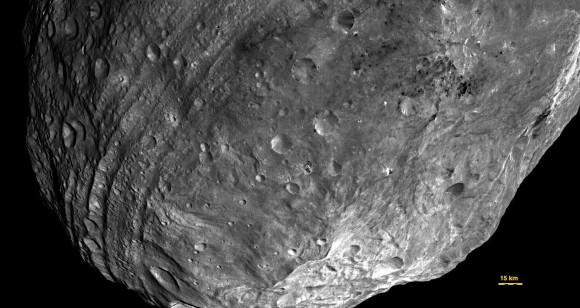

Like all comets, ISON is a clump of frozen gases mixed with dust. Often described as “dirty snowballs,” comets emit gas and dust whenever they venture near enough to the Sun that the icy material transforms from a solid to gas, a process called sublimation. Jets powered by sublimating ice also release dust, which reflects sunlight and brightens the comet.

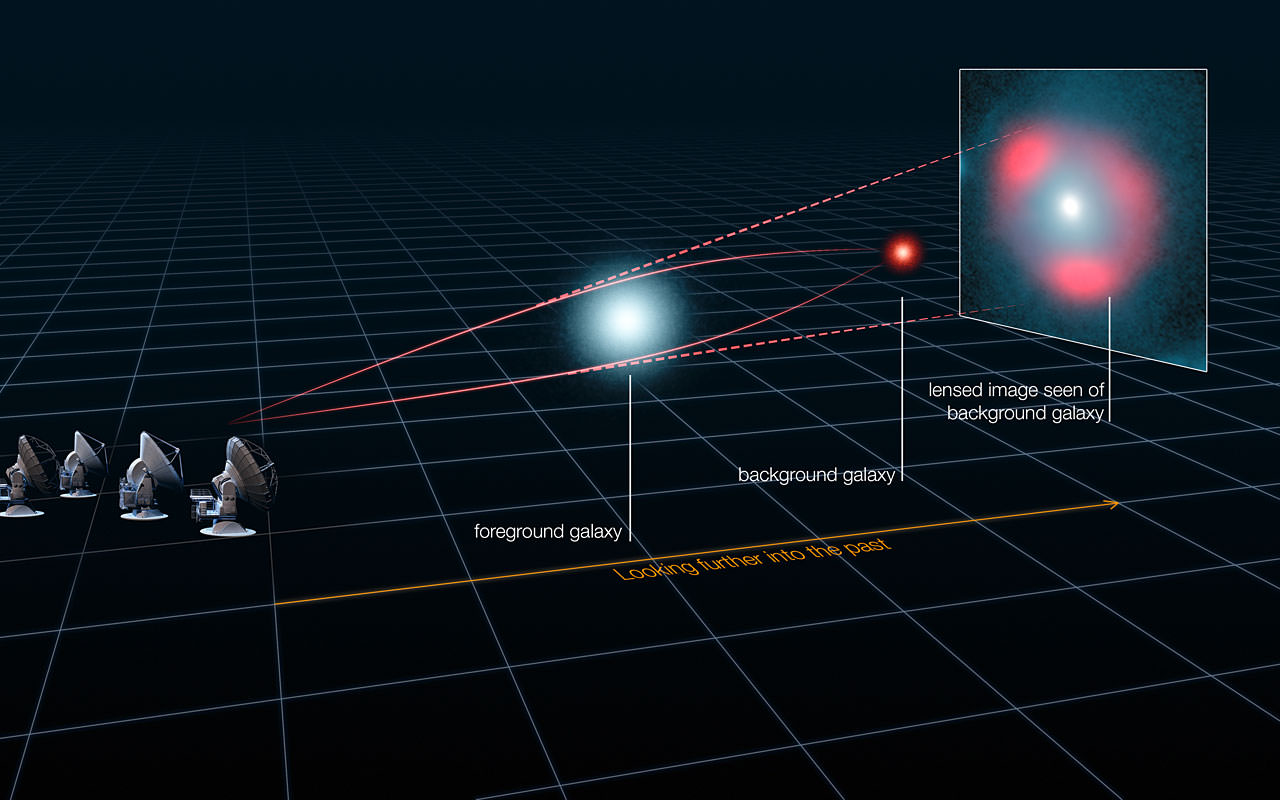

Typically, a comet’s water content remains frozen until it comes within about three times Earth’s distance to the Sun. While Swift’s UVOT cannot detect water directly, the molecule quickly breaks into hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl (OH) molecules when exposed to ultraviolet sunlight. The UVOT detects light emitted by hydroxyl and other important molecular fragments as well as sunlight reflected from dust.

The Deep Impact spacecraft also imaged Comet ISON in mid-January, and NASA and ESA are planning an observing campaign with the rovers and orbiters at Mars around October 1 when the inbound comet passes about 6.7 million miles (10.8 million km) from Mars.

“During this close encounter, comet ISON may be observable to NASA and ESA spacecraft now working at Mars,” said Michael Kelley, an astronomer at UMCP and also a Swift and CIOC team member. “Personally, I’m hoping we’ll see a dramatic postcard image taken by NASA’s latest Mars explorer, the Curiosity rover.”

Fifty-eight days later, on Nov. 28, ISON will make a sweltering passage around the Sun. The comet will approach within about 730,000 miles (1.2 million km) of its visible surface, which classifies ISON as a sungrazing comet. In late November, its icy material will furiously sublimate and release torrents of dust as the surface erodes under the sun’s fierce heat, all as sun-monitoring satellites look on. Around this time, the comet may become bright enough to glimpse just by holding up a hand to block the sun’s glare.

An important question is whether ISON will continue to brighten at the same pace once water evaporation becomes the dominant source for its jets. Will the comet sizzle or fizzle?

“It looks promising, but that’s all we can say for sure now,” said Matthew Knight, an astronomer at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, and a member of the Swift and CIOC teams. “Past comets have failed to live up to expectations once they reached the inner solar system, and only observations over the next few months will improve our knowledge of how ISON will perform.”

Based on ISON’s orbit, astronomers think the comet is making its first-ever trip through the inner solar system. Before beginning its long fall toward the Sun, the comet resided in the Oort comet cloud, a vast shell of perhaps a trillion icy bodies that extends from the outer reaches of the planetary system to about a third of the distance to the star nearest the Sun.

Formally designated C/2012 S1 (ISON), the comet was discovered on Sept. 21, 2012, by Russian astronomers Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok using a telescope of the International Scientific Optical Network located near Kislovodsk.

Sungrazing comets often shed large fragments or even completely disrupt following close encounters with the Sun, but for ISON neither fate is a forgone conclusion.

“We estimate that as much as 10 percent of the comet’s diameter may erode away, but this probably won’t devastate it,” explained Knight. Nearly all of the energy reaching the comet acts to sublimate its ice, an evaporative process that cools the comet’s surface and keeps it from reaching extreme temperatures despite its proximity to the sun.

Following ISON’s solar encounter, the comet will depart the sun and move toward Earth, appearing in evening twilight through December. It will swing past Earth on Dec. 26, approaching within 39.9 million miles (64.2 million km) or about 167 times farther than the Moon.

Source: NASA