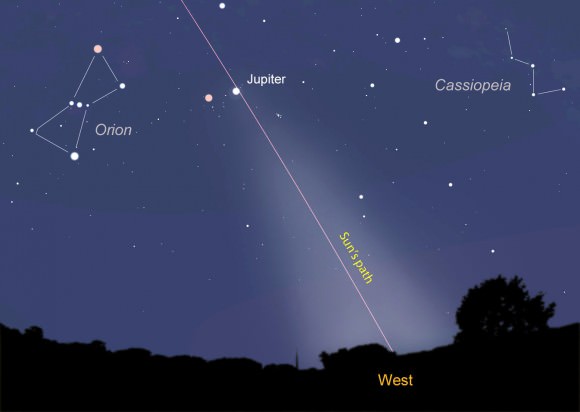

With the much-anticipated PANSTARRS comet emerging into the evening sky this week, we might keep our eyes open to another sight happening at nearly the same time. If you live where the sky to the west is very dark, look for the zodiacal light, a tapering cone of softly-luminous light slanting up from the western horizon toward the bright planet Jupiter near twilight’s end.

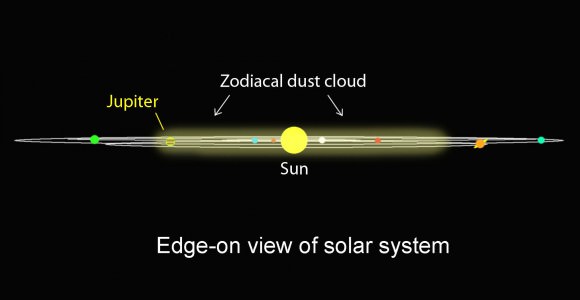

It makes its first appearance about 75 minutes after sunset and lingers for an hour and a half. Sunlight reflected from countless dust particles shed by comets and to a lesser degree by colliding asteroids is responsible for this little-noticed phenomenon. Comets orbiting approximately in the plane of the solar system between Jupiter and the sun are its key contributors. Jupiter’s gravity stirs the works into a pancake-like cloud that permeates the inner solar system.

More of us would be more aware of the zodiacal light if we knew better when and where to look. While a dark sky is essential, you don’t have to move to the Atacama Desert. I live 9 miles from a moderate-sized, light-polluted city; the western sky is terrible but the east is plenty dark and ideal for watching the morning zodiacal light in the fall months.

Near its base, the cone easily matches the summer Milky Way in brightness and spans about two fists held horizontally at arm’s length. At first glance you’d be tempted to think it was the lingering glow of twilight until you realize it’s nearly two hours after sunset. The farther you follow up the cone, the fainter and narrower it becomes. From top to bottom the light pyramid measures nearly five fists long. In other words, it’s HUGE.

The zodiacal light is centered on the same path the sun and planets take through the sky called the ecliptic, an imaginary circle that runs through the familiar 12 constellations of the zodiac. Every spring, that path intersects the western horizon at dusk at a steep angle, tilting the light cone up into clear view. A similar situation happens in the eastern sky before dawn in October. Of course the light’s there all year long, but we don’t notice it because it’s slanted at a lower angle and blends into the hazy air near the horizon.

The zodiacal light we see at dusk is a portion of the larger zodiacal dust cloud that extends at least to Jupiter’s distance (~500 million miles) on either side of the Sun, making it the single biggest thing in the Solar System visible with the naked eye. Under exceptional skies, like those found on distant mountaintops or far from city lights, the cone tapers into the zodiacal band that completely encircles the sky.

Exactly opposite the sun around local midnight, you might see an enhancement in the band called the gegenschein (GAY-gen-shine). This eerie oval glow is caused by sunlight shining directly on interplanetary dust grains and then back to your eye. A similar boost happens for the same reason at the time of full moon.

Deep connections abound throughout the universe. Over time, much of the comet dust in the zodiacal cloud either spirals inward toward the sun or gets pushed outward by solar radiation. The fact that we can still see it today means it’s continually being replenished by the silent comings and goings of comets.

Credit: Jim Gifford

Consider Comet L4 PANSTARRS. Dribs and drabs of dust sputtered from this comet during its current trip to the inner solar system may find their way into the zodiacal cloud to secure its presence for future sky watchers. How wonderful then the comet and the ghostly light should happen to be at their best the very same time of year.

Now through March 13 is the ideal time for zodiacal light viewing. If you begin your evening with Comet PANSTARRS, stick around until nightfall to spot the light. Face west and cast a wide view across the sky, sweeping your gaze from left to right and back again. Look for a big, hazy glow reaching from the horizon toward the Planet Jupiter. After the 13th, the waxing moon will wash out the subtle light cone for a time. Another “zodiacal window” opens up in late March through mid-April when the moon comes up too late to spoil the view.

As you take in the sight, consider how something as small as a dust mote, when teamed with its mates, can create a jaw-dropping comet’s tail, meet its end in the fiery finale of a meteor shower or span a billion miles of space.