This Week’s Best Space Photos – April 26, 2013.

An Inside Look at the Water/Urine Recycling System on the Space Station

International Space Station Commander Chris Hadfield “lifts the lid” on the Water Recovery System, the first liquid recycling system to be flown in space that cleans almost all the “water” (greywater, urine, sweat) produced by crew members so that it can be used again. As previous space station resident Don Pettit has said, “Yesterday’s coffee becomes today’s coffee.”

Previously, Russia’s space station Mir recycled cosmonaut’s sweat, but this system on the ISS can recycle about 93 percent of the liquids it receives. The ISS’s water recycler uses a distiller that looks like a keg. On Earth, distilling is a simple process of boiling water and cooling the steam back into pure water. But without gravity, the contaminants in water never separate from the steam no matter how much heat is used. So, the keg-sized distiller spins to produce an artificial gravity field while boiling the water. The contaminants in the urine or greywater press against the sides of the drum while the steam gathers in the middle and is pumped to a filter.

Radio Observatory Moves to a Shopping Mall

How’s this for bringing science to the public? This weekend, the Onsala Space Observatory in Sweden will be moving their telescope’s control room to Scandinavia’s biggest shopping mall, Nordstan (North Town) in Gothenburg.

“The idea is to remotely observe with our 20-meter telescope — as well as a couple of smaller ones — and let the general public take part and see how it’s done and how exciting it is,” the observatory’s public relations director Robert Cumming told Universe Today.”

The great thing about radio astronomy is that is can be done during the day – during business hours at the mall.

And they’ve got some interesting targets on the list, including Comet Lemmon. “It’s too close to the sun for ordinary telescopes, but for a radio telescope like ours that’s no problem,” said Cumming.

Of course, the radio telescope itself still has to be out at its normal location, away from radio interference, but the control room will move to allow public interaction. But there will be bus tours available out to the big telescope.

But beyond public outreach, looking at Comet Lemmon gives the astronomers at Onsala practice for the (hopefully) big one this fall, Comet ISON. “Onsala will have one of very few telescopes that can study ISON from the Earth,” Cumming said.

So, for any of our readers in Sweden, head out the North Town Mall in Gothenburg between the hours of 11:00 and 16:00 local time on Sunday, April 28. This is part of the Gothenburg Science Festival.

“It is the first time we are trying to make a telescope control room outside Onsala,” said Mitra Hajigholi, graduate student in astronomy at Chalmers University of Technology, who will be one of several researchers on location at the mall. “With the help of our large 20-meter telescope, we want to look at a comet and display measurements in real time. It will be exciting!”

You Can Remove All Ads from Universe Today

I just wanted to remind everyone, if you don’t want advertising mixed in with your space news, you can remove them permanently with a 1-time donation to Universe Today. I’ll switch you over to a Member Account, and all the ads will be automatically removed for your viewing pleasure.

One donation.

Any amount, no matter how small.

All ads removed from Universe Today forever.

P.S. To the 270 Universe Today members, your support means so much to us. Thank you!

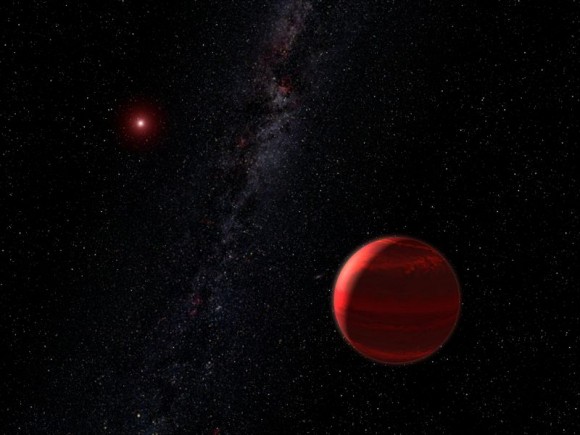

How Do You Measure A Planet Near A Tiny Star?

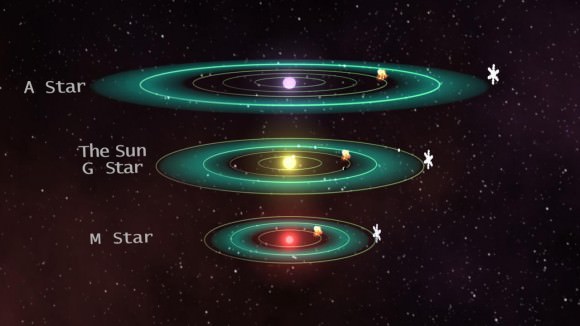

When you sit back and think about how far away exoplanets are — and how faint — it’s a scientific feat that we can find these distant worlds outside our Solar System at all. It’s even harder to learn about the world if the exoplanet is orbiting a dim star — say, about two-thirds the size of the Sun — that is faint through even the largest telescope.

In response to this problem, there’s one science team that thinks it’s found a way to solve it. Their research bumped a planet from the habitable zone to the not-so-friendly zone of a star. Here’s how it happened:

The usual way to measure a distant star is this: look at the light. A Sun-sized star, for example, would have its light waves measured at different wavelengths. Scientists then match what they see to spectra (light bands) that are created artificially.

This method doesn’t work so well for smaller stars, though. “The challenge is that small stars are incredibly difficult to characterize,” stated Sarah Ballard, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Washington, in a press release. Worse, these small guys make up about two-thirds of the stars in the universe.

Ballard led a multi-university team describing a “characterization by proxy” method accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal and now available online.

The science team based their work on previous research performed by astronomer Tabetha Boyajian, who is currently at Yale University.

Boyajian combined the resources of several telescopes that measured wavelengths of light, wavelengths that are slightly longer than visible light. This technique allowed the interferometer (the combined telescopes) to figure out the size of stars that are close by.

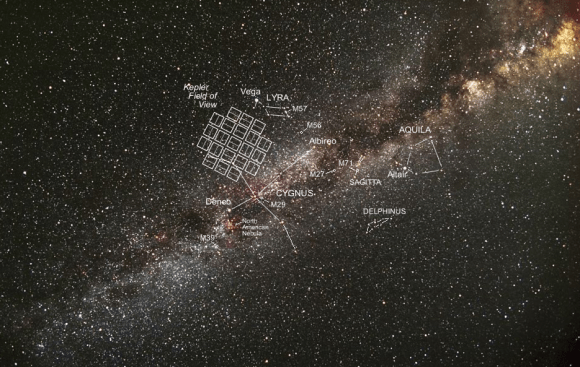

With that data on hand, Ballard and her colleagues looked out into the universe. Their target was Kepler-61b (Kepler Object 1361.01), a “candidate” planet about double the size of Earth spotted by the planet-hunting Kepler space telescope. The candidate, if proven, is orbiting a low-mass star 900 light-years away that is hard to measure in a telescope.

Next, the scientists picked four nearby stars that have similar light patterns, reasoning that they would be spectroscopially close enough to Kepler-61b’s parent star to make accurate measurements. The four stars are located in Ursa Major and Cygnus, ranging between 12 to 25 light years away from Earth.

When the scientists compared the measurements to Kepler 61’s star, a surprise emerged.

“Kepler-61 turned out to be bigger and hotter than expected,” the University of Washington stated. “This in turn recalibrated planet Kepler-61b’s relative size upward as well — meaning it, too, would be hotter than previously thought and no longer a resident of the star’s habitable zone.”

The newly refined planetary radius for Kepler-61b is 2.15 times the radius of Earth (plus or minus 0.13 radii). Astronomers estimate it orbits its star about once every 59.9 days and has a temperature of 273 Kelvin (plus or minus 13 Kelvin.)

Just to wrap up, here’s a note about how likely it is that Kepler-61b is actually a planet — and not a planetary candidate.

The candidate was first described in this 2011 scientific paper. Kepler-61b is just one in a long list of 1,235 planetary candidates catalogued in that paper, all discovered in just four months — between May 2 and Sept. 16, 2009.

While the NASA Exoplanet Archive still lists Kepler-61b as a candidate planet — one that must be confirmed by independent observations — this 2011 paper says that most Kepler candidates have a strong possibility of being actual planets because the Kepler software is technologically apt.

In other words, Ballard and her co-authors write in the research, Kepler-61b is very likely to be a planet itself — with only 4.8 percent possibility of being a “false positive”, to be exact.

Source: University of Washington

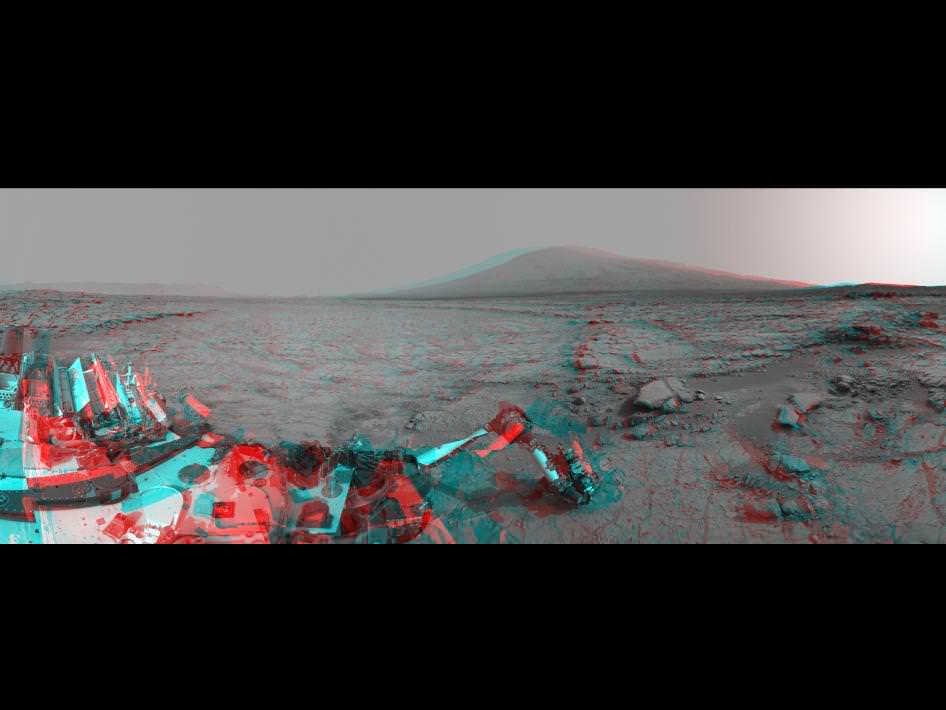

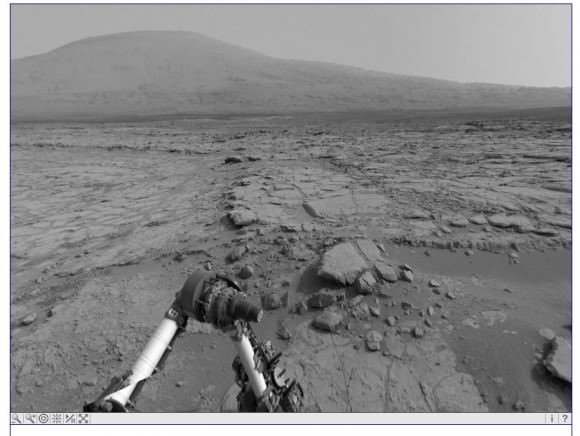

New Interactive Panorama from the Curiosity Rover

Above is a recent 3-D version of a panoramic view from NASA of the Curiosity Mars rover, made from dozens of images from both the left and right Navcams. But panoramic specialist John O’Connor has also put together a non-3-D interactive view of this scene of the rover and its surroundings. The images were taken during the 166th, 168th and 169th Martian days, or sols, of Curiosity’s work on Mars, which equates to Jan. 23, 25 and 26, 2013 here on Earth.

Check out the interactive panorama here, or below. It will probably come up as full-screen, and you can use your mouse to interact and move around. Or just hit ‘escape’ if you’d rather not be in full-screen mode. You can still use the mouse to move around wherever you want to go, or use the toolbar on the lower left for more options. This is a high-def view so feel free to zoom in for details!

We haven’t heard much from Curiosity lately because Mars is still in solar conjunction, where Mars and Earth are on opposite sides of the Sun from each other, meaning communications are basically worthless between the two planets. Our powerful Sun interrupts radio transmissions between Earth and the Mars rovers and orbiters, and data to and from the spacecraft might get corrupted. So, to avoid any problems, the spacecraft (and spacecraft engineers and scientists) take a little time off; the solar conjunction serves as a little spring break. But things should be back at full-throttle by next week.

For the 3-D view above (click on it to see a larger view), use red-blue glasses with the red lens on the left. It spans 360 degrees, with Mount Sharp on the southern horizon.

In the center foreground, the rover’s arm holds the tool turret above a target called “Wernecke” on the “John Klein” patch of pale-veined mudstone. On Sol 169, Curiosity used its dust-removing brush and Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) on Wernecke. About two weeks later, Curiosity used its drill at a point about 1 foot (30 centimeters) to the right of Wernecke to collect the first drilled sample from the interior of a rock on Mars.

Sci-Fi Book Review: “Pilot” by R.D. Drabble

“Pilot,” a new sci-fi thriller, follows law enforcement officer Legitt Redd, as he finds himself in the middle of an extraordinary set of circumstances. It is set in a solar system where humans occupy 6 life-supporting planets. Each planet has a different role to the civilisation, one being an energy source, another a prison, another a holiday destination, for example. Legitt is a low ranking officer whom serves for the oppressive government, ‘The Ministry.’ He is introduced as a fairly ordinary, uninspired man whose main duty is to transport prisoners to and from the Prison planet Gorby for processing. He has a long standing friendship and affiliation with one such prisoner – Afyd Geller whom has a reputation as a leader in the underworld and has the respect of many amongst law enforcement. Once a free man, Afyd often invites Leggit for drinking sessions. It‘s on one of these ordinary drinking sessions that the out-of-the-ordinary sequence of events begins. After a few adventure and violent encounters, they travel to the Litton where the apparent real figure head of the underworld resides. Leggit find out that the mythical ‘boogie man’ of child stories of old, Murlon Furlong is in fact a real person, and the all-powerful ruler of criminals.

Murlon sets Leggit, Afyd and other members of this motley crew, on a task to kidnap a spiritual leader. There is a back story of the civilisation’s theology which, in short includes the beginning of time and the eventual coming of salvation.

When this goes horribly wrong Legitt realises his true potential, and attempts to conquer Murlon and avoid swift and violent punishment of The Ministry. This means a whole lot more than he realises and intends the reader to question what is good and what is evil.

This book has great potential. Author R.D. Drabble paints pictures with his words, as if he can see them all around him. Initially this was inspiring to read. You can really imagine the frames in which Drabble was describing. But this positive is also a negative and too much visual description means at times it reads like a script, rather than a novel. There is only the present tense and only one story line, which leaves the reader feeling a bit flat with this one dimensional presentation of an otherwise interesting plot. It would have been a lot more enjoyable if there was a sub-plot or scenes that did not include the main character. Even though Leggit was in every scene, I still felt I didn’t have much insight into him as a character.

Having said that, there are definitely great moments. The technological creations and concepts found in Pilot are really inspiring. They seem to mix the spiritual human elements with technological fantasy. And the Drabble paints an Orwell-esque picture of the Ministry ruled worlds, and there were some phrases that were so poignant and poetic, that is will make you read them twice. The book starts of in a very certain black and white view of the world but progresses a grey outlook, at the same time that character Legitt questions his own morality in certain situations.

But these great moments are sandwiched between cliché, yet lovable characters and the many un-foreshadowed random unnecessary scenarios. There is an appendix of illustrations to support the story lines and backstories, but these don’t really add value or are explored.

Having said that it is clear that Drabble has an amazing amount of imagination. The 6 worlds and their stories are quiet intricate and to be honest, could be explored further in future books. I hope Drabble can express this obvious talent of imagination in future stories, especially if they are in comic or graphic novel format.

Overall, it’s a great read with some cool concepts.

R.D. Drabble is an electrician and science fiction fanatic who has had a lifelong obsession with the strange and inexplicable. It was his love for the unusual that inspired him to write his debut novel Pilot.

Pilot is available on Amazon.com and Lulu.com

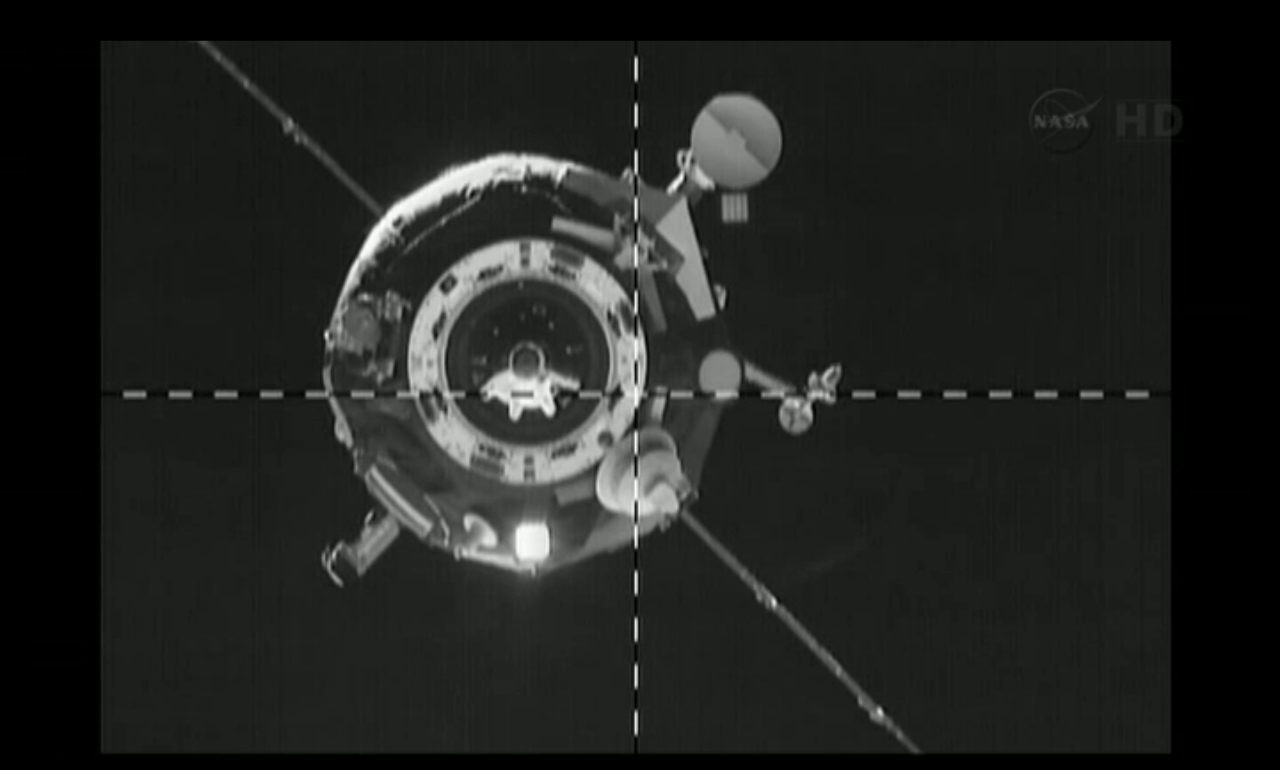

Success! Progress Spacecraft Overcomes Stuck Antenna, Arrives at Station

A software fix solved a sticky antenna problem on an unmanned cargo ship, a problem that threatened to interfere with the approach and docking to the International Space Station Friday.

Progress 51 successfully docked with the massive orbiting complex at 8:35 a.m. EDT (12:35 p.m. GMT) Friday without the need of assistance from the station crew, which was standing by to take over the docking just in case.

“Progress is safely docked! Big moment for the crew. Hooray!” wrote astronaut Chris Hadfield, the commander of Expedition 35, on Twitter moments after the spacecraft and station docked.

Watch all the action in the video, below:

Crew members are expected to start unloading the three tons of food, fuel, supplies and experiment on board later today (Friday), if all goes according to schedule.

The Russian supply ship has five antennas on board that are used for approaching the station for a docking using the KURS automated system. One of them refused to unfurl as usual after the spacecraft launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on Wednesday (April 24).

As a backup, crew members could bring the spacecraft in using a manual system that also allows them to view the station from a camera inside Progress.

This particular antenna, NASA said, is normally used to help keep the vehicle properly oriented as it gets closer to the station.

When the Progress spacecraft and station are 65 feet (20 meters) apart, the antenna also provides data on the relative roll of the vehicle with respect to the station.

NASA initially told the crew it was expected to bring the spacecraft in manually. Shortly after 6 a.m. EDT (10 a.m. GMT), however, capsule communicator David Saint-Jacques radioed that NASA was confident a software patch created by Russian ground controllers would address the problem.

Progress 51’s final approach proceeded normally, but controllers took it a little slower than usual to ensure the automated system was working properly with the fix. The approach started slightly early, allowing capture to occur at 8:25 a.m. EDT (12:25 p.m. GMT) — two minutes earlier than planned.

Ground control and the Expedition 35 crew then spent several minutes verifying that the antenna would not interfere with the docking port. With crew members saying they couldn’t hear any funny noises from inside the station, NASA went forward with the hard docking.

Follow updates from Expedition 35 at Universe Today, and live on NASA’s television channel online.

Astrophotographers Capture “Mini” Lunar Eclipse

The lunar eclipse on April 25 was described by astrophotographer Gadi Eidelheit as “the greatest, slightest eclipse I ever saw!” The brief and small eclipse saw just 1.47% of the lunar limb nicked by the dark umbra or shadow from the Earth. It was visible from eastern Europe and Africa across the Middle East eastward to southeast Asia and western Australia. Here are a few more shots, including a serendipitous shot of an airplane flying through the eclipse!

Want to get your astrophoto featured on Universe Today? Join our Flickr group or send us your images by email (this means you’re giving us permission to post them). Please explain what’s in the picture, when you took it, the equipment you used, etc.

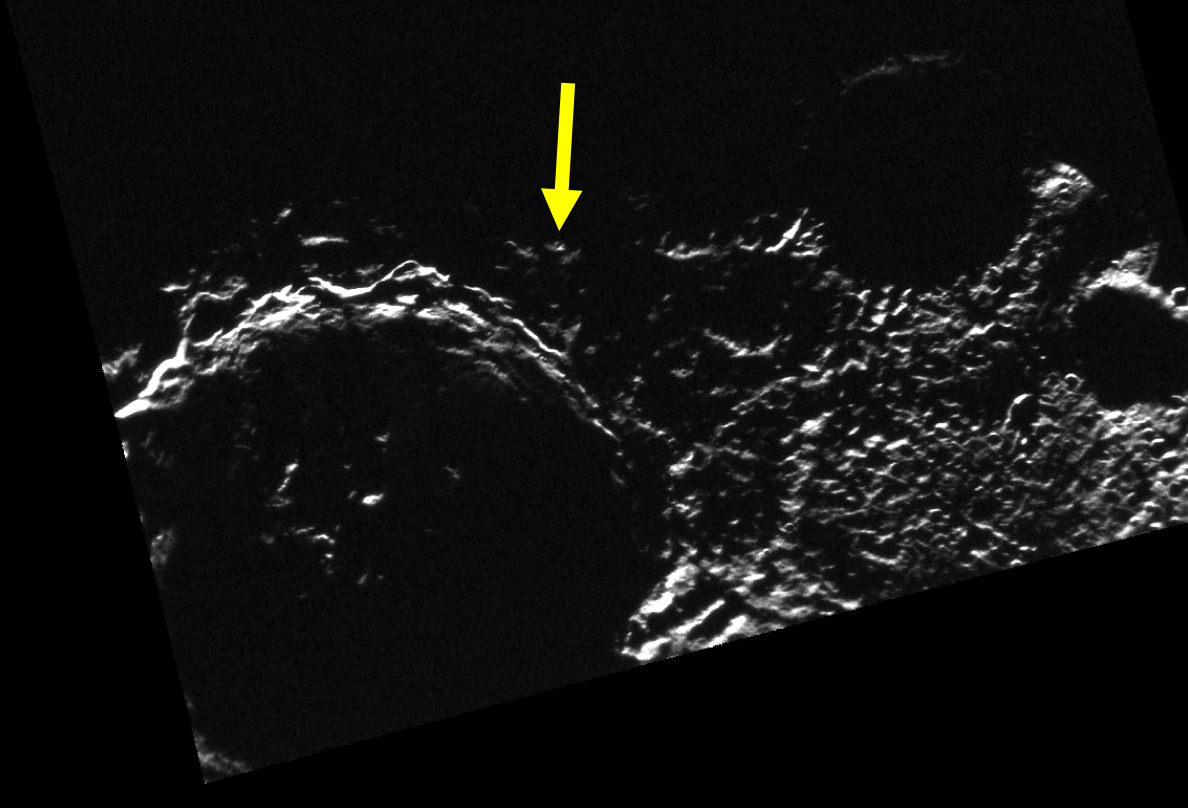

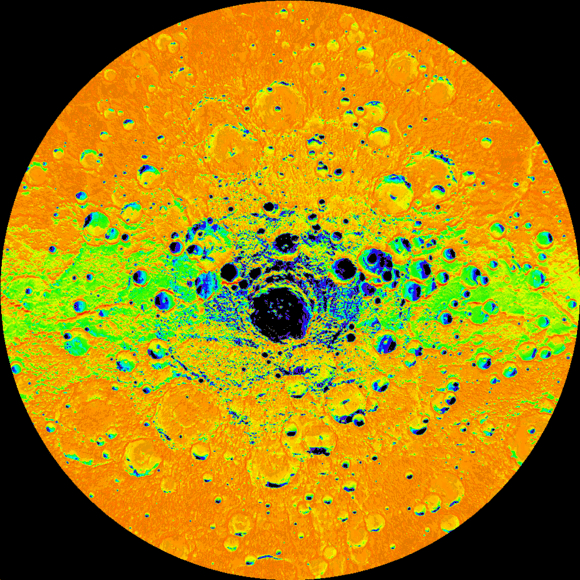

This Spot on Mercury (Almost) Never Goes Dark

Mercury, traveling in its 88-day-long orbit around the Sun with basically zero axial tilt, has many craters at its poles whose insides literally never see the light of day. These permanently-shadowed locations have been found by the MESSENGER mission to harbor considerable deposits of ice (a seemingly ironic discovery on a planet two-and-a-half times closer to the Sun than we are!*)

But if there are places on Mercury where the Sun never shines (insert butt joke here) then there may also be places where it always does. That’s what researchers are looking for in illumination maps made from MESSENGER data… and they’re getting closer.

The image above shows a region near Mercury’s south pole. The yellow arrow points to the closest thing to a true “peak of eternal light” found thus far on Mercury, a point that receives sunlight about 82% of the time — almost constantly illuminated.

From the JHUAPL MESSENGER mission site:

Studies of the illumination conditions near the north and south poles of Mercury are of interest because they can be used to determine locations of permanent shadow, extremely cold places where ice deposits lurk. However, the illumination maps also reveal the locations that receive the maximum duration of sunlight during a Mercury solar day.

A “peak of eternal light” that is illuminated continuously for an entire solar day would be a favorable target for a lander, because solar power would be available all the time. So far, no such peak of eternal light has been identified at Mercury’s south pole.

The spot that get the most illumination (about 82%), is located at 89° S, 50.7° E.

This image was acquired as part of MDIS’s campaign to monitor the south polar region of Mercury. By imaging the polar region approximately every four MESSENGER orbits as illumination conditions change, features that were in shadow on earlier orbits can be discerned and any permanently shadowed areas can be identified after repeated imaging over one solar day.

“A ‘peak of eternal light’ that is illuminated continuously for an entire solar day would be a favorable target for a lander, because solar power would be available all the time.”

The top image above was acquired on Dec. 24, 2011. The large crater is Chao Meng-Fu, about 129 km (80 mi.) in diameter. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

*Without an atmosphere to hold and distribute heat, any place on Mercury that stays in shadow for any length of time will remain very cold — plenty cold enough for water ice to remain rock-hard indefinitely.