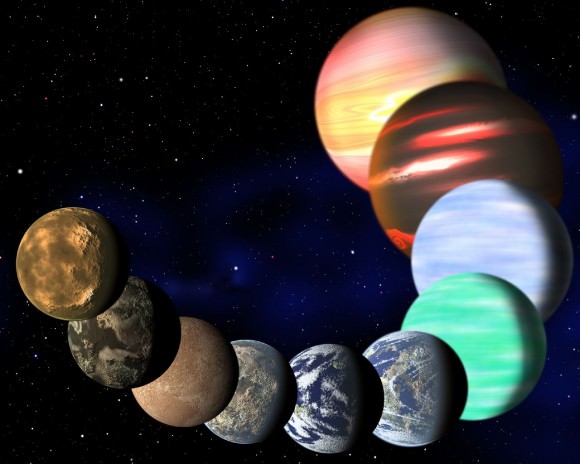

The latest analysis of data from the Kepler planet-hunting spacecraft reveals that almost all stars have planets, and about 17 percent of stars have an Earth-sized planet in an orbit closer than Mercury. Since the Milky Way has about 100 billion stars, there are at least 17 billion Earth-sized worlds out there, according to Francois Fressin of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), who presented new findings today in a press conference at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Long Beach, California. Moreover, he said, almost all Sun-like stars have planetary systems.

The holy grail of planet-hunting is finding a twin of Earth – a planet of about the same size and in the habitable zone around similar star. The odds of finding such a planet is becoming more likely Fressin said, as the latest analysis shows that small planets are equally common around small and large stars.

While the list of Kepler planetary candidates contains majority of the knowledge we have about exoplanets, Fressin said the catalog is not yet complete, and the catalog is not pure. “There are false positives from events such as eclipsing binaries and other astrophysical configurations that can mimic planet signals,” Fressin said.

By doing a simulation of the Kepler survey and focusing on the false positives, they can only account for 9.5% of the huge number of Kepler candidates. The rest are bona-fide planets.

Altogether, the researchers found that 50 percent of stars have a planet of Earth-size or larger in a close orbit. By adding larger planets, which have been detected in wider orbits up to the orbital distance of the Earth, this number reaches 70 percent.

Extrapolating from Kepler’s currently ongoing observations and results from other detection techniques, it looks like practically all Sun-like stars have planets.

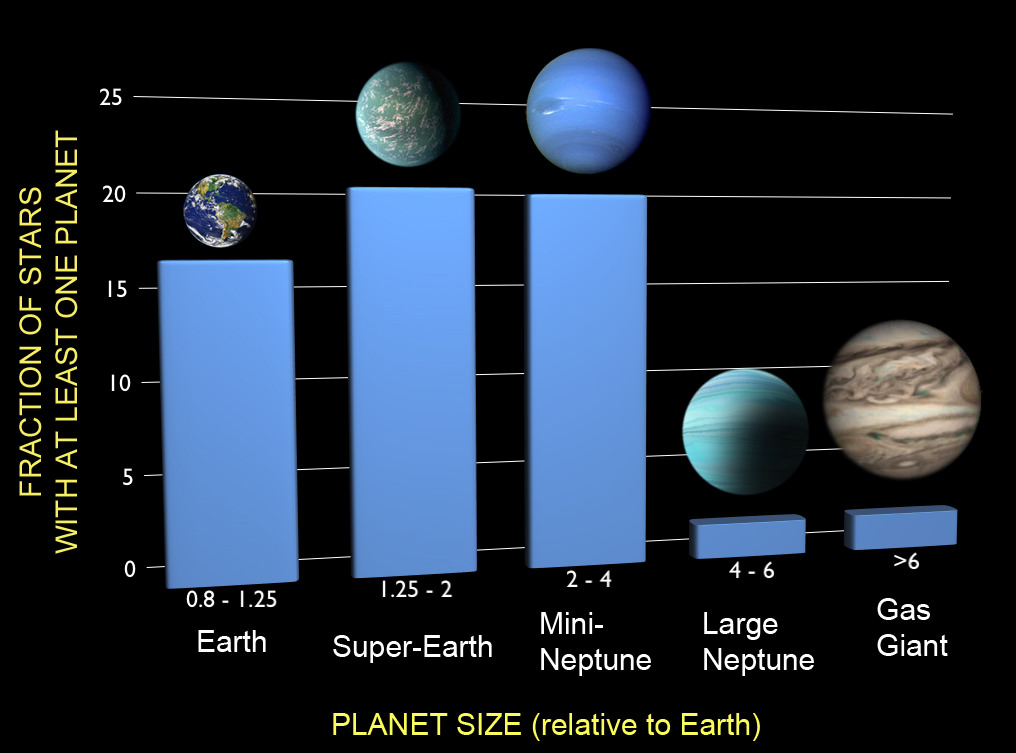

The team then grouped planets into five different sizes. They found that 17 percent of stars have a planet 0.8 – 1.25 times the size of Earth in an orbit of 85 days or less. About one-fourth of stars have a super-Earth (1.25 – 2 times the size of Earth) in an orbit of 150 days or less. (Larger planets can be detected at greater distances more easily.) The same fraction of stars has a mini-Neptune (2 – 4 times Earth) in orbits up to 250 days long.

Larger planets are much less common. Only about 3 percent of stars have a large Neptune (4 – 6 times Earth), and only 5 percent of stars have a gas giant (6 – 22 times Earth) in an orbit of 400 days or less.

The researchers also asked whether certain sizes of planets are more or less common around certain types of stars. They found that for every planet size except gas giants, the type of star doesn’t matter. Neptunes are found just as frequently around red dwarfs as they are around sun-like stars. The same is true for smaller worlds. This contradicts previous findings.

“Earths and super-Earths aren’t picky. We’re finding them in all kinds of neighborhoods,” says co-author Guillermo Torres of the CfA.

Planets closer to their stars are easier to find because they transit more frequently. As more data are gathered, planets in larger orbits will come to light. In particular, Kepler’s extended mission should allow it to spot Earth-sized planets at greater distances, including Earth-like orbits in the habitable zone.

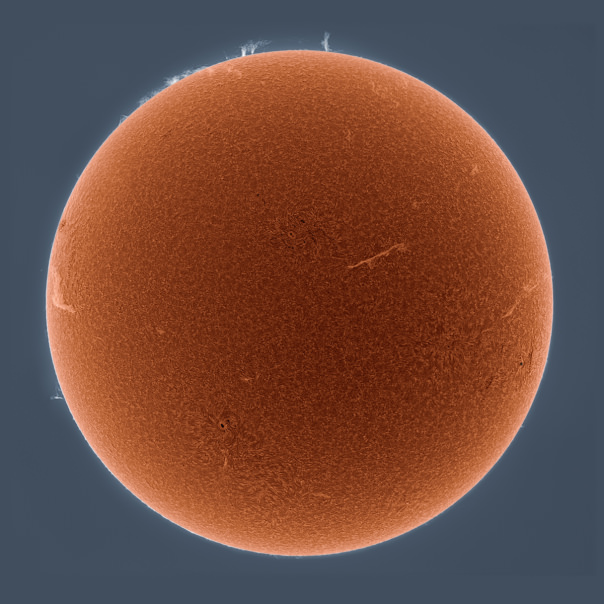

Kepler detects planetary candidates using the transit method, watching for a planet to cross its star and create a mini-eclipse that dims the star slightly.

Sources: Harvard Smithsonian CfA, AAS Press Conference