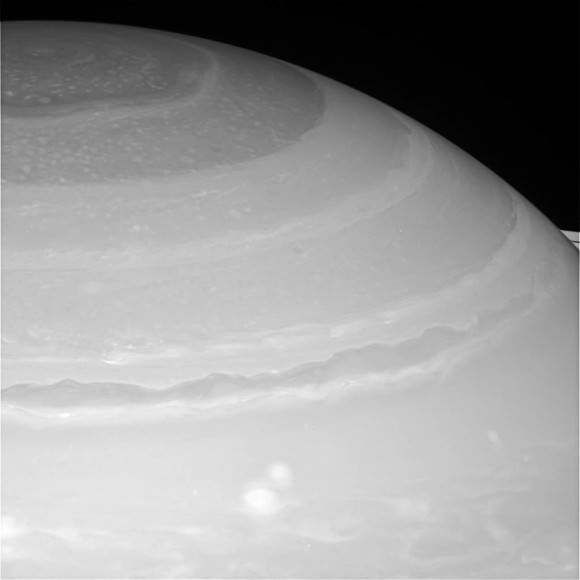

Lake Vida lies within one of Antarctica’s cold, arid McMurdo Dry Valleys (Photo: Desert Research Institute)

Even inside an almost completely frozen lake within Antarctica’s inland dry valleys, in dark, salt-laden and sub-freezing water full of nitrous oxide, life thrives… offering a clue at what might one day be found in similar environments elsewhere in the Solar System.

Researchers from NASA, the Desert Research Institute in Nevada, the University of Illinois at Chicago and nine other institutions have discovered colonies of bacteria living in one of the most isolated places on Earth: Antarctica’s Lake Vida, located in Victoria Valley — one of the southern continent’s incredibly arid McMurdo Dry Valleys.

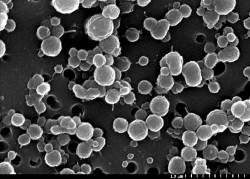

These organisms seem to be thriving despite the harsh conditions. Covered by 20 meters (65 feet) of ice, the water in Lake Vida is six times saltier than seawater and contains the highest levels of nitrous oxide ever found in a natural body of water. Sunlight doesn’t penetrate very far below the frozen surface, and due to the hypersaline conditions and pressure of the ice water temperatures can plunge to a frigid -13.5 ºC (8 ºF).

Yet even within such a seemingly inhospitable environment Lake Vida is host to a “surprisingly diverse and abundant assemblage of bacteria” existing within water channels branching through the ice, separated from the sun’s energy and isolated from exterior influences for an estimated 3,000 years.

Yet even within such a seemingly inhospitable environment Lake Vida is host to a “surprisingly diverse and abundant assemblage of bacteria” existing within water channels branching through the ice, separated from the sun’s energy and isolated from exterior influences for an estimated 3,000 years.

Originally thought to be frozen solid, ground penetrating radar surveys in 1995 revealed a very salty liquid layer (a brine) underlying the lake’s year-round 20-meter-thick ice cover.

“This study provides a window into one of the most unique ecosystems on Earth,” said Dr. Alison Murray, one of the lead authors of the team’s paper, a molecular microbial ecologist and polar researcher and a member of 14 expeditions to the Southern Ocean and Antarctic continent. “Our knowledge of geochemical and microbial processes in lightless icy environments, especially at subzero temperatures, has been mostly unknown up until now. This work expands our understanding of the types of life that can survive in these isolated, cryoecosystems and how different strategies may be used to exist in such challenging environments.”

Sterile environments had to be set up within tents on Lake Vida’s surface so the researchers could be sure that the core samples they were drilling were pristine, and weren’t being contaminated with any introduced organisms.

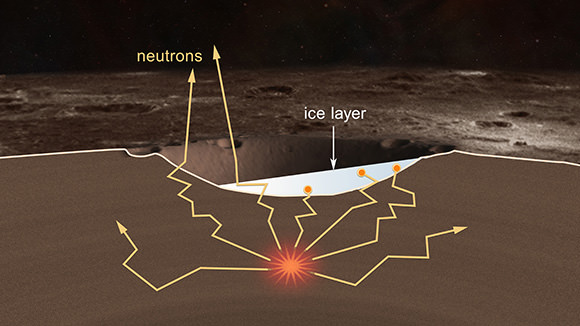

According to a NASA press release, “geochemical analyses suggest chemical reactions between the brine and the underlying iron-rich sediments generate nitrous oxide and molecular hydrogen. The latter, in part, may provide the energy needed to support the brine’s diverse microbial life.”

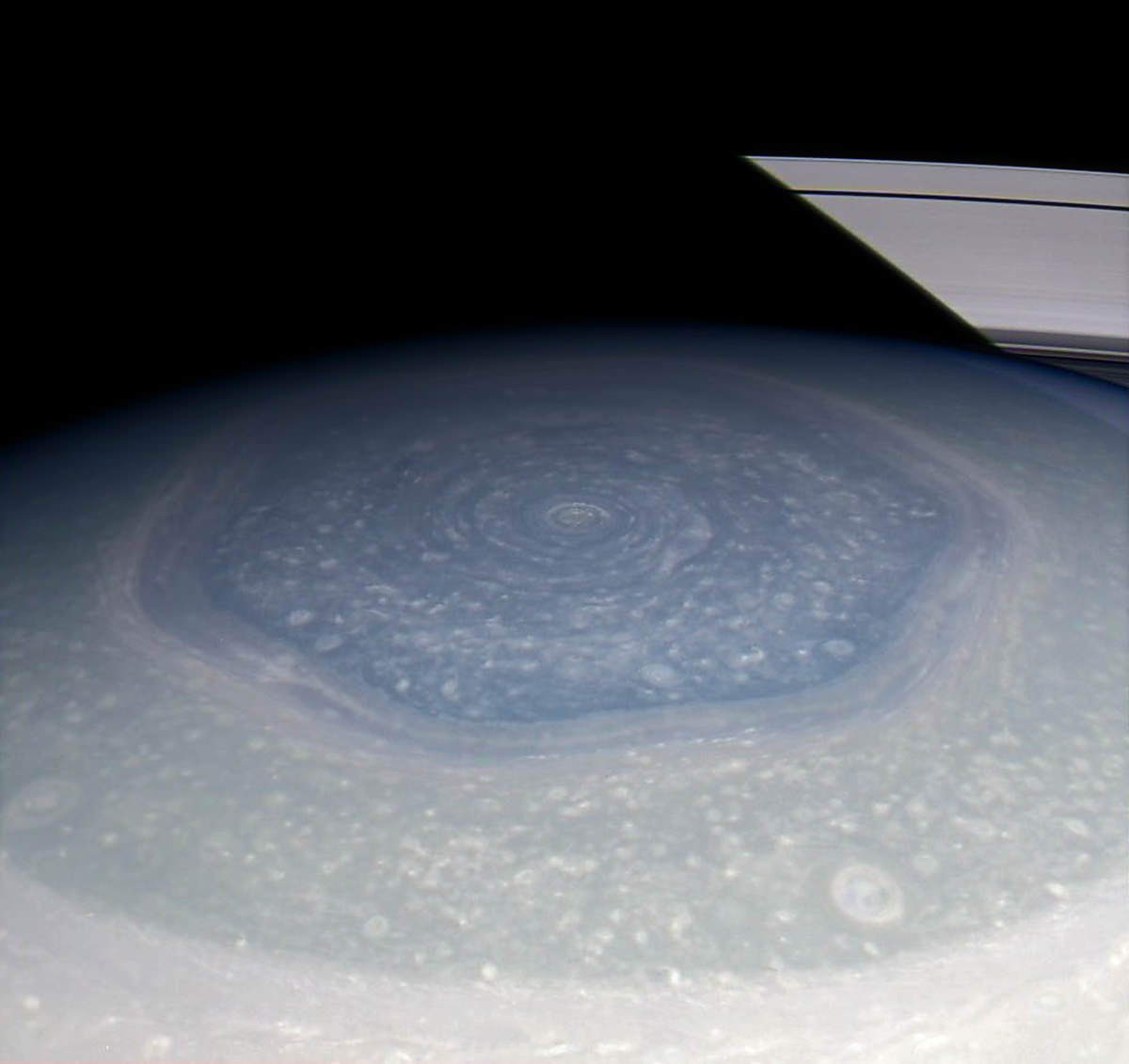

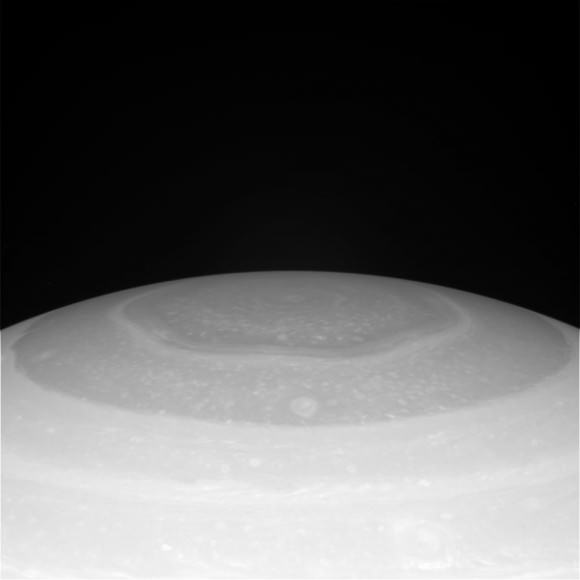

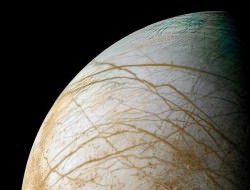

“This system is probably the best analog we have for possible ecosystems in the subsurface waters of Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa.”

– Chris McKay, co-author, NASA’s Ames Research Center

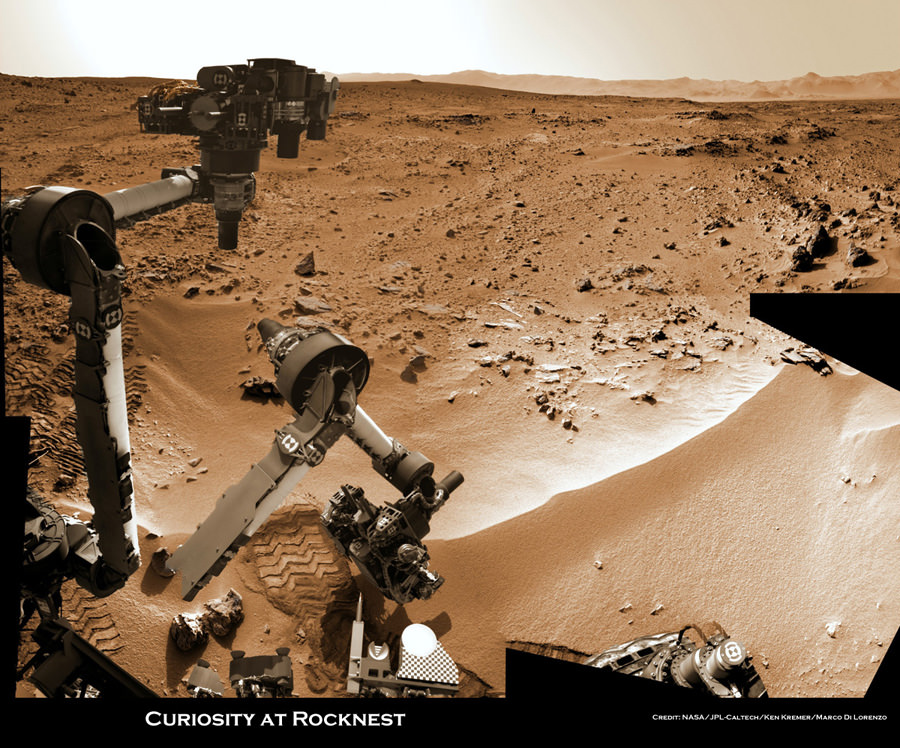

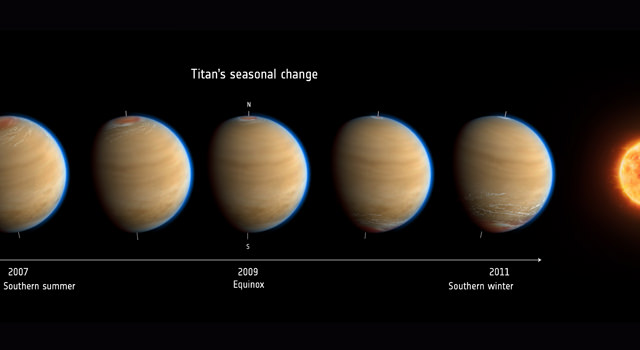

What’s particularly exciting is the similarity between conditions found in ice-covered Antarctic lakes and those that could be found on other worlds in our Solar System. If life could survive in Lake Vida, as harsh and isolated as it is, could it also be found beneath the icy surface of Europa, or within the (hypothesized) subsurface oceans of Enceladus? And what about the ice caps of Mars? Might there be similar channels of super-salty liquid water running through Mars’ ice, with microbes eking out an existence on iron sediments?

What’s particularly exciting is the similarity between conditions found in ice-covered Antarctic lakes and those that could be found on other worlds in our Solar System. If life could survive in Lake Vida, as harsh and isolated as it is, could it also be found beneath the icy surface of Europa, or within the (hypothesized) subsurface oceans of Enceladus? And what about the ice caps of Mars? Might there be similar channels of super-salty liquid water running through Mars’ ice, with microbes eking out an existence on iron sediments?

“It’s plausible that a life-supporting energy source exists solely from the chemical reaction between anoxic salt water and the rock,” explained Dr. Christian Fritsen, a systems microbial ecologist and Research Professor in DRI’s Division of Earth and Ecosystem Sciences and co-author of the study.

“If that’s the case,” Murray added, “this gives us an entirely new framework for thinking of how life can be supported in cryoecosystems on earth and in other icy worlds of the universe.”

Read more: Europa’s Hidden Great Lakes May Harbor Life

More research is planned to study the chemical interactions between the sediment and the brine as well as the genetic makeup of the microbial communities themselves.

The research was published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS). Read more on the DRI press release here, and watch a video below showing highlights from the field research.

Funding for the research was supported jointly by NSF and NASA. Images courtesy the Desert Research Institute. Dry valley image credit: NASA/Landsat. Europa image: NASA/Ted Stryk.)