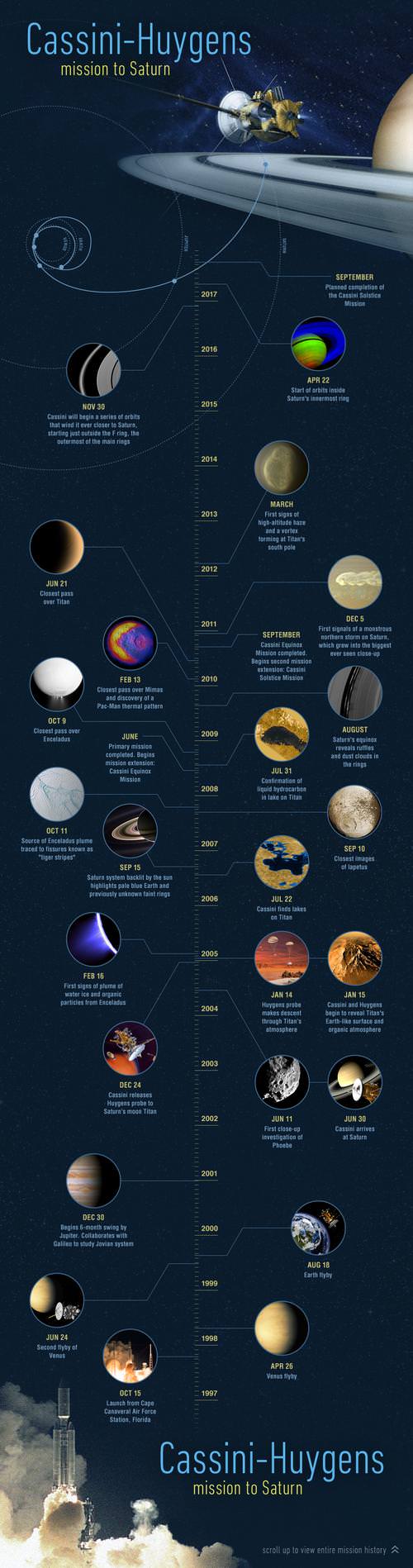

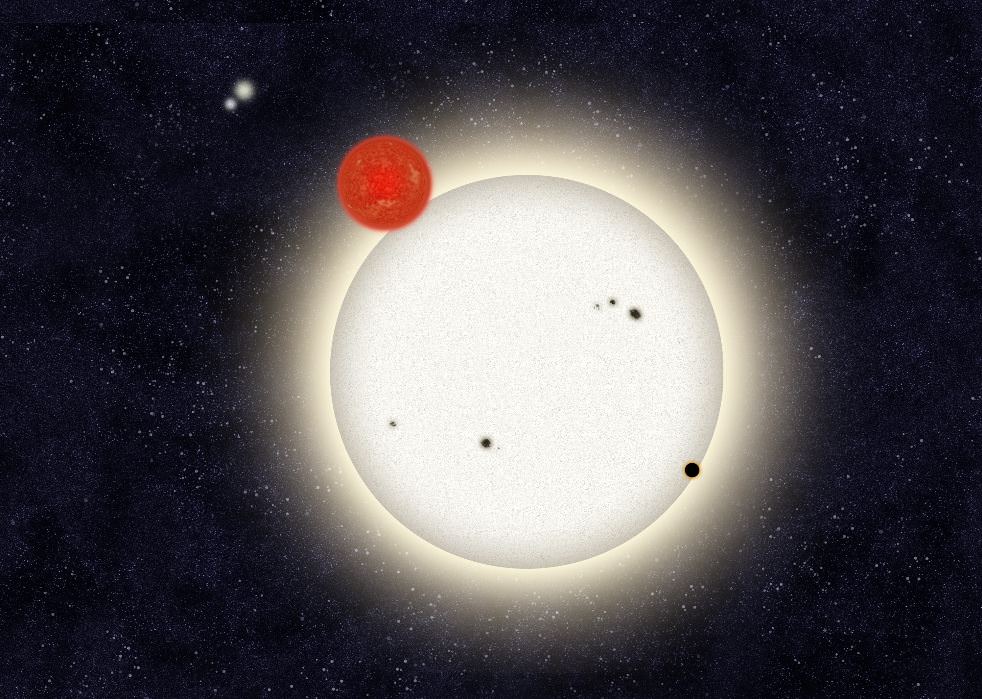

Hubble’s view of massive galaxy cluster MACS J0717.5+3745. The large field of view is a combination of 18 separate Hubble images. Credit:

NASA, ESA, Harald Ebeling (University of Hawaii at Manoa) & Jean-Paul Kneib (LAM)

Earlier this year, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope were able to identify a slim filament of dark matter that appeared to be binding a pair of distant galaxies together. Now, another filament has been found, and scientists a have been able to produce a 3-D view of the filament, the first time ever that the difficult-to-detect dark matter has been able to be measured in such detail. Their results suggest the filament has a high mass and, the researchers say, that if these measurements are representative of the rest of the Universe, then these structures may contain more than half of all the mass in the Universe.

Dark matter is thought to have been part of the Universe from the very beginning, a leftover from the Big Bang that created the backbone for the large-scale structure of the Universe.

“Filaments of the cosmic web are hugely extended and very diffuse, which makes them extremely difficult to detect, let alone study in 3D,” said Mathilde Jauzac, from Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille in France and University of KwaZulu-Natal, in South Africa, lead author of the study.

The team combined high resolution images of the region around the massive galaxy cluster MACS J0717.5+3745 (or MACS J0717 for short) – one of the most massive galaxy clusters known — and found the filament extends about 60 million light-years out from the cluster.

The team said their observations provide the first direct glimpse of the shape of the scaffolding that gives the Universe its structure. They used Hubble, NAOJ’s Subaru Telescope and the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, with spectroscopic data on the galaxies within it from the WM Keck Observatory and the Gemini Observatory. Analyzing these observations together gives a complete view of the shape of the filament as it extends out from the galaxy cluster almost along our line of sight.

The team detailed their “recipe” for studying the vast but diffuse filament. .

First ingredient: A promising target. Theories of cosmic evolution suggest that galaxy clusters form where filaments of the cosmic web meet, with the filaments slowly funnelling matter into the clusters. “From our earlier work on MACS J0717, we knew that this cluster is actively growing, and thus a prime target for a detailed study of the cosmic web,” explains co-author Harald Ebeling (University of Hawaii at Manoa, USA), who led the team that discovered MACS J0717 almost a decade ago.

Second ingredient: Advanced gravitational lensing techniques. Albert Einstein’s famous theory of general relativity says that the path of light is bent when it passes through or near objects with a large mass. Filaments of the cosmic web are largely made up of dark matter [2] which cannot be seen directly, but their mass is enough to bend the light and distort the images of galaxies in the background, in a process called gravitational lensing. The team has developed new tools to convert the image distortions into a mass map.

Third ingredient: High resolution images. Gravitational lensing is a subtle phenomenon, and studying it needs detailed images. Hubble observations let the team study the precise deformation in the shapes of numerous lensed galaxies. This in turn reveals where the hidden dark matter filament is located. “The challenge,” explains co-author Jean-Paul Kneib (LAM, France), “was to find a model of the cluster’s shape which fitted all the lensing features that we observed.”

Finally: Measurements of distances and motions. Hubble’s observations of the cluster give the best two-dimensional map yet of a filament, but to see its shape in 3D required additional observations. Colour images [3], as well as galaxy velocities measured with spectrometers [4], using data from the Subaru, CFHT, WM Keck, and Gemini North telescopes (all on Mauna Kea, Hawaii), allowed the team to locate thousands of galaxies within the filament and to detect the motions of many of them.

A model that combined positional and velocity information for all these galaxies was constructed and this then revealed the 3D shape and orientation of the filamentary structure. As a result, the team was able to measure the true properties of this elusive filamentary structure without the uncertainties and biases that come from projecting the structure onto two dimensions, as is common in such analyses.

The results obtained push the limits of predictions made by theoretical work and numerical simulations of the cosmic web. With a length of at least 60 million light-years, the MACS J0717 filament is extreme even on astronomical scales. And if its mass content as measured by the team can be taken to be representative of filaments near giant clusters, then these diffuse links between the nodes of the cosmic web may contain even more mass (in the form of dark matter) than theorists predicted.

More info in this ESA HubbleCast video:

Source: ESA Hubble