Astronomers have known for some time there was one star orbiting fairly close to the black hole at the center of our galaxy. But now another star has been found dipping close and orbiting even faster around the Milky Way’s central black hole. Astronomer Andrea Ghez from UCLA says the ability to watch these two stars in a short-period ‘tango’ around the black hole will help scientist measure the effects of space-time curvature, and they should be able to determine whether Albert Einstein was right in his prediction of how black holes could warp space and time.

“I’m extremely pleased to find two stars that orbit our galaxy’s supermassive black hole in much less than a human lifetime,” said Ghez. “It is the tango of [these stars] that will reveal the true geometry of space and time near a black hole for the first time. This measurement cannot be done with one star alone.”

There are nearly 3,000 stars that orbit somewhat close to the black hole, and most of them have orbits of 60 years or longer.

The previously known close-in star, S0-2, orbits the black hole every 15.5 years. And now, the newly found star, called S0-102, orbits the black hole in a blazing 11.5 years, the shortest known orbit of any star near this black hole.

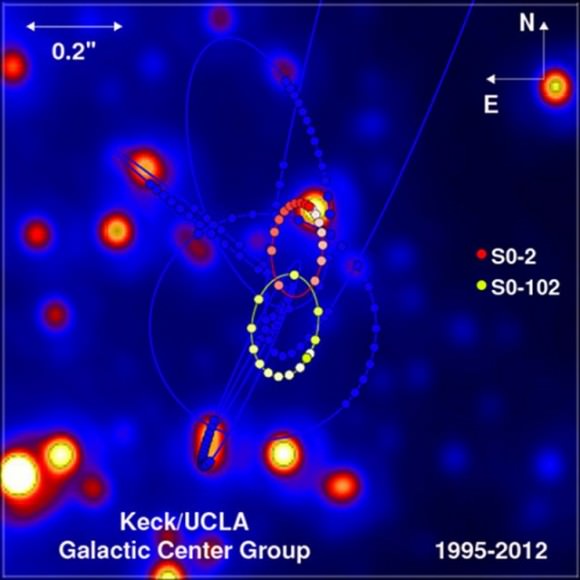

Reconstruction of the orbits of two stars—S0-2 and S0-102—near the black hole at the Milky Way’s center. (Other stars’ orbits are also depicted by fainter lines.) The background is a real high-resolution infrared image of the region. Credit: Andrea Ghez et al./UCLA/Keck

In the same way that planets orbit around the sun, S0-102 and S0-2 are each in an elliptical orbit around the central black hole. Ghez said that the planetary motion in our solar system was the ultimate test for Newton’s gravitational theory 300 years ago, and now the motion of S0-102 and S0-2 will be the ultimate test for Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which describes gravity as a consequence of the curvature of space and time.

“The exciting thing about seeing stars go through their complete orbit is not only that you can prove that a black hole exists but you have the first opportunity to test fundamental physics using the motions of these stars,” Ghez said. “Showing that it goes around in an ellipse provides the mass of the supermassive black hole, but if we can improve the precision of the measurements, we can see deviations from a perfect ellipse — which is the signature of general relativity.”

As the stars come to their closest approach, their motion will be affected by the curvature of spacetime, and the light traveling from the stars to us will be distorted, Ghez said.

S0-2, which is 15 times brighter than S0-102, will go through its closest approach to the black hole in 2018. S0-102 makes its closest approach in 2021, so the team will be keeping an eye on these stars as they get tantalizingly close, but not close enough to get sucked in, Ghez said.

Ghez and her colleagues have been observing S0-2 since 1995. In 2000, she and her team reported — for the first time – that astronomers had seen stars accelerate around the supermassive black hole. Their research demonstrated that three stars had accelerated by more than 250,000 mph a year as they orbited the black hole. The speed of S0-102 and S0-2 should also accelerate by more than 250,000 mph at their closest approach, Ghez said.

“The fact that we can find stars that are so close to the black hole is phenomenal,” said Ghez. “Now it’s a whole new ballgame, in terms of the kinds of experiments we can do to understand how black holes grow over time, the role supermassive black holes play in the center of galaxies, and whether Einstein’s theory of general relativity is valid near a black hole, where this theory has never been tested before. It’s exciting to now have a means to open up this window.”

The research was done using the Keck Telescopes. The team’s paper was published Oct. 5 in the journal Science.

Source: UCLA

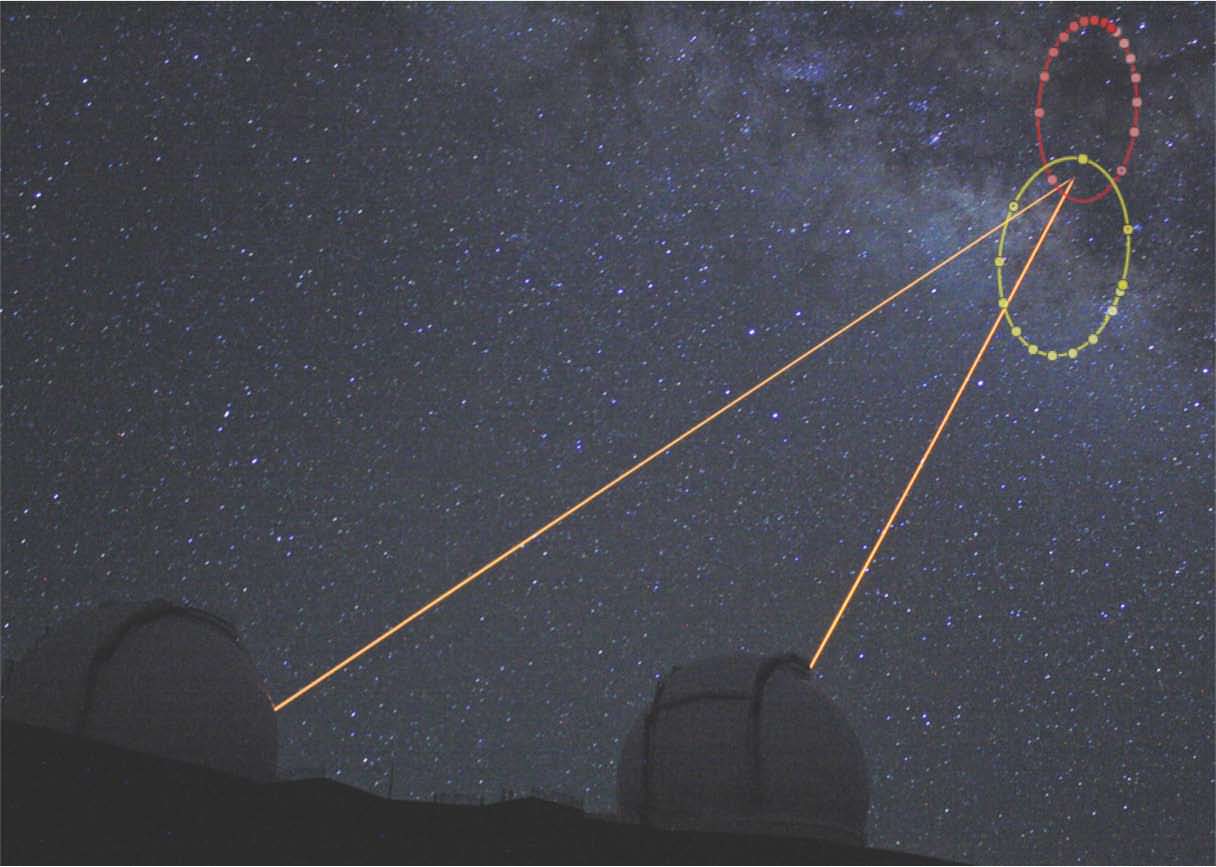

Lead image caption: The Keck I and Keck II telescopes focus on two stars orbiting Milky Way’s black hole. Background photo credit: Dan Birchall/Subaru Telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. Overlay created by Professor Andrea Ghez and her research team at UCLA and are from data sets obtained with the W. M. Keck Telescopes.