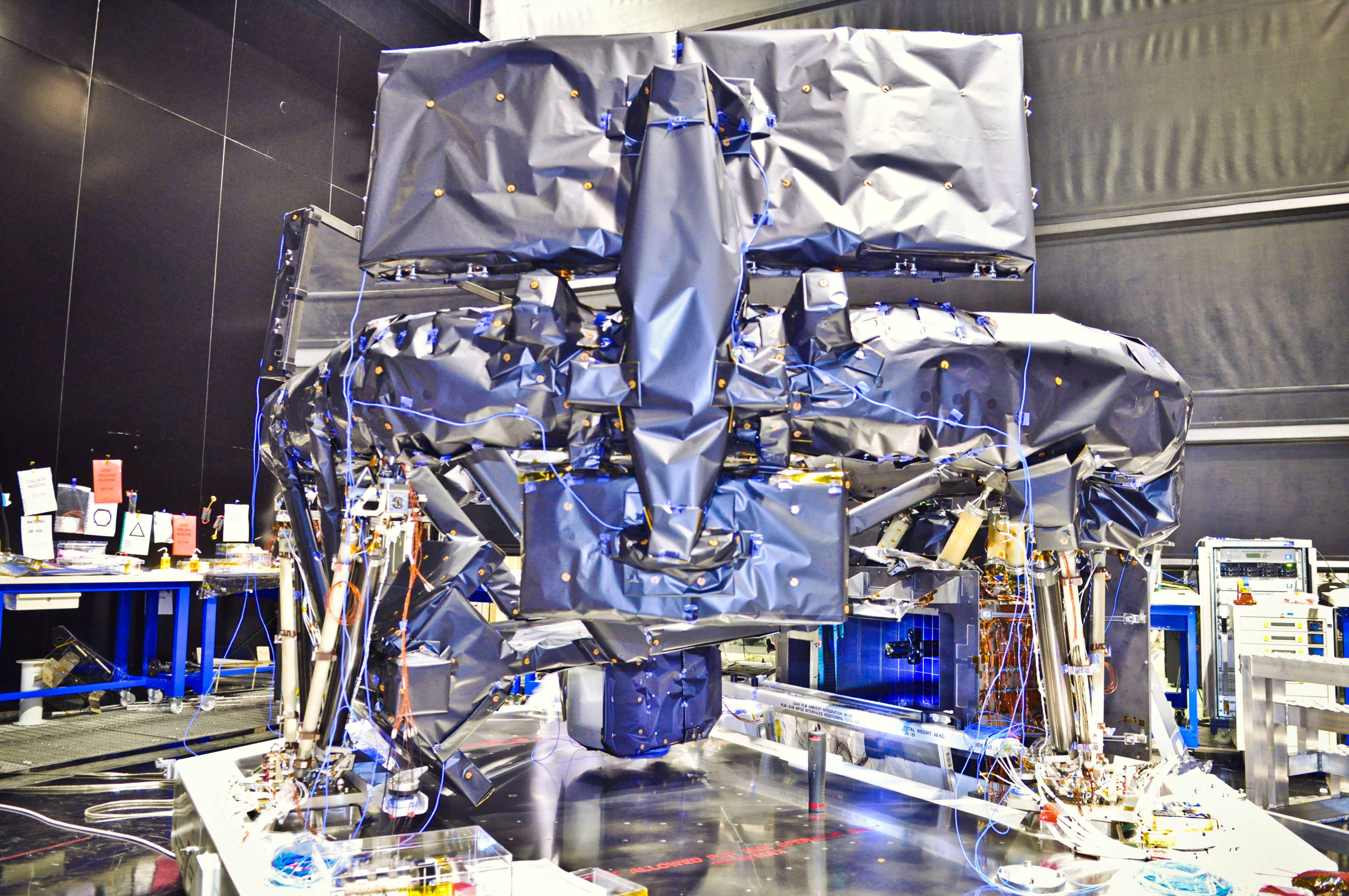

Caption: Fully integrated Gaia payload module with nearly all of the multilayer insulation fabric installed. Credit: Astrium SAS

Earlier this month ESA’s Gaia mission passed vital tests to ensure it can withstand the extreme temperatures of space. This week in the Astrium cleanroom at Intespace in Toulouse, France, had it’s payload module integrated, ready for further testing before it finally launches next year. This is a good opportunity to get to know the nuts and bolts of this exciting mission that will survey a billion stars in the Milky Way and create a 3D map to reveal its composition, formation and evolution.

Gaia will be operating at a distance of 1.5 million km from Earth (at L2 Lagrangian point, which keeps pace with Earth as we orbit the Sun) and at a temperature of -110°C. It will monitor each of its target stars about 70 times over a five-year period, repeatedly measuring the positions, to an accuracy of 24 microarcseconds, of all objects down to magnitude 20 (about 400,000 times fainter than can be seen with the naked eye) This will provide detailed maps of each star’s motion, to reveal their origins and evolution, as well as the physical properties of each star, including luminosity, temperature, gravity and composition.

The service module houses the electronics for the science instruments and the spacecraft resources, such as thermal control, propulsion, communication, and attitude and orbit control. During the 19-day tests earlier this month, Gaia endured the thermal balance and thermal-vacuum cycle tests, held under vacuum conditions and subjected to a range of temperatures. Temperatures inside Gaia during the test period were recorded between -20°C and +70°C.

“The thermal tests went very well; all measurements were close to predictions and the spacecraft proved to be robust with stable behavior,” reports Gaia Project Manager Giuseppe Sarri.

For the next two months the same thermal tests will be carried out on Gaia’s payload module, which contains the scientific instruments. The module is covered in multilayer insulation fabric to protect the spacecraft’s optics and mirrors from the cold of space, called the ‘thermal tent.’

Gaia contains two optical telescopes that can precisely determine the location of stars and analyze their spectra. The largest mirror in each telescope is 1.45 m by 0.5 m. The Focal Plane Assembly features three different zones associated with the science instruments: Astro, the astrometric instrument that detects and pinpoints celestial objects; the Blue and Red Photometers (BP/RP), that determines stellar properties like temperature, mass, age, elemental composition; and the Radial-Velocity Spectrometer (RVS),that measures the velocity of celestial objects along the line of sight.

The focal plane array will also carry the largest digital camera ever built with, the most sensitive set of light detectors ever assembled for a space mission, using 106 CCDs with nearly 1 billion pixels covering an area of 2.8 square metres

After launch, Gaia will always point away from the Sun. L2 offers a stable thermal environment, a clear view of the Universe as the Sun, Earth and Moon are always outside the instruments’ fields of view, and a moderate radiation environment. However Gaia must still be shielded from the heat of the Sun by a giant shade to keep its instruments in permanent shadow. A ‘skirt’ will unfold consisting of a dozen separate panels. These will deploy to form a circular disc about 10 m across. This acts as both a sunshade, to keep the telescopes stable at below –100°C, and its surface will be partially covered with solar panels to generate electricity.

Once testing is completed the payload module will be mated to the service module at the beginning of next year and Gaia will be launched from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana at the end of 2013.

Find out more about the mission here