Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! Normally we don’t pay much attention to the waning Moon, but this week will be a bit different. Why not enjoy some alternative studies by viewing familiar features in a different light?! Of course, we might just pick up a galaxy or catch a snowball! When you’re ready, just meet me in the back yard…

Monday, October 1 – In 1897, the world’s largest refractor (40?) debuted at the dedication of the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory. The immense telescope was 64 feet long and weighed 6 tons. Also today in 1958, NASA was established by an act of Congress. More? In 1962, the 300 foot radio telescope of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) went live at Green Bank, West Virginia. It held its place as the world’s second largest radio scope until it collapsed in 1988. (It was rebuilt as a 100 meter dish in 2000.) Although first light for the 40? was Jupiter, E. E. Barnard later discovered the third companion star to Vega using the Yerkes refractor and first “light” studies at Green Bank were a radio source galaxy and pulsar for NRAO.

Tonight let’s begin our adventures by talking about Luna 9, also known as Lunik 9. In 1966, the unmanned Soviet lunar probe became the first to achieve a soft landing on the Moon’s surface and successfully transmit photographs back to Earth. The lander weighed in at 99 kg, and the four petals, which formed the spacecraft, opened outward. Within five minutes of landing, antennae sprang to life and the television cameras began broadcasting back the first panoramic images of the surface of another world, proving that a landing would not simply sink into the lunar dust. Last contact with the spacecraft occurred just before midnight on February 6, 1966.

Tonight you can view the area of the first successful landing on the Moon by turning your binoculars or telescopes copes towards the Oceanus Procellarum—the Ocean of Storms. While the area will be brightly lit and it will be difficult to pick out small features, Procellarum is the long, dark expanse that runs from lunar north to south. On its western edge, you can easily identify the dark oval of landmark crater Grimaldi. About one Grimaldi-length northward and on the western shore of Procellarum is where you would find the remains of Luna 9.

Tuesday, October 2 – Tonight before the skies get bright we’ll a have look at an incredible southern galaxy in Sculptor – NGC 253 (Right Ascension: 0 : 47.6 – Declination: -25 : 17).

Located about one third the way between Alpha Sculptor and Beta Ceti, NGC 253 was discovered by Caroline Herschel in 1783 during a comet search. As the brightest member of the “Sculptor Group”, this large and beautiful galaxy is also one of the closest outside our “Local Group” and will be readily apparent in binoculars for southern observers. Mid-to-large telescopes will be delighted with its many bright knots and dark obscured areas. For more northern observers, wait until the constellation is at its highest to catch a glimpse of this awesome 7th magnitude southern study.

Now, let’s wait for the Moon to rise!

For a telescope challenge, continue south to relocate previous study Petavius on the southern terminator. Just beyond its east wall, look for a bright ridge that extends from north to south separated by darkness from Petavius. This is Palitzsch, a very strange, gorge-like formation that looks as if it was caused by a meteor plowing through the Moon’s surface. Palitzsch’s true nature wasn’t known until 1954 when Patrick Moore resolved it as a “crater chain” using the 25″ Newall refractor at Cambridge University Observatory. While you’re admiring Petavius and its branching rima, keep in mind this 80 kilometer long crack is a buckle in the lava flow across the crater floor. Now look along the terminator for the long, dark runnel which is often considered to be the Petavius Wall but is actually the fascinating crater Palitzsch. This 41 kilometer wide crater is confluent with a 110 kilometer long valley that is outstanding at this phase!

Wednesday, October 3 – Tonight let’s go hunting for the “Blue Snowball”. It’s proper name is the NGC 7662 (Right Ascension: 23 : 25.9 – Declination: +42 : 33) and you find it around five degrees due east of Omicron Andromedae. At magnitude 9, this one challenges binocular users and presents the same problems as locating the M57 – low power will show you something – but not what it is. In a telescope, the “Blue Snowball” is almost as large as the “Ring” nebula.

Are you ready for the Moon to rise? Then let’s continue our waning studies…

As Mare Crisium slowly disappears into the shadows, let’s take a look for a lunar challenge crater – Macrobius. You’ll find it just northwest of the Crisium shore. Spanning 64 kilometers in diameter, this Class I impact crater drops to a depth of nearly 3600 meters – about the same as many of our earthly mines. Its central peak rises back up, and at 1100 meters may be visible as a small speck inside the crater’s interior. Power up and look at how steep its crater slopes are. Can you spot the smaller impact crater Macrobius O to the southeast and conjoining crater Tisserand to the east? Check out how the sunlight highlights the the west and southwest walls. In this particular light you can see how high and terraced they really are! Look for the impact of Macrobius C to the southwest.

In binoculars, look for the junction of Mare Fecunditatis and the edge of Mare Tranquillitatis. Here stands ancient Taruntius. Like a “lighthouse” guarding the shores, it stands on a mountainous peninsula overlooking the mare and shooting its brilliant beams across the desolate landscape nearly 175 kilometers.. Tonight it appears as a bright ring, but watch in the days ahead as it turns into just another crater.

Thursday, October 4 – Today in 1957, the USSR’s Sputnik 1 made space history as it became the first manmade object to orbit the earth. The Earth’s first artificial satellite was tiny, roughly the size of a basketball, and weighed no more than the average man. Every 98 minutes it swung around Earth in its elliptical orbit and changed everything. It was the beginning of the “Space Race.” Many of us old enough to remember Sputnik’s grand passes will also recall just how inspiring it was. Take the time with your children or grandchildren to check heavens-above.com for visible passes of the ISS and think about how much our world has changed in just 50 years!

Tonight we’re headed towards the southwest corner star of the Great Square of Pegasus – Alpha. Our goal will be 11th magnitude NGC 7479 located about 3 degrees south (RA 23:04.9 Dec +12:19).

Discovered by Sir William Herschel in 1784 and cataloged as H I.55, this barred spiral galaxy can be spotted in average telescopes and comes to beautiful life with larger aperture. Also known as Caldwell 44 on Sir Patrick Moore’s observing list, what makes this galaxy special is its delicate “S” shape. Smaller scopes will easily see the central bar structure of this 105 million light-year distant island universe, and as aperture increases, the western arm will become more dominant. This arm itself is a wonderful mystery – containing more mass than it should and a turbulent structure. It is believed that perhaps a minor merger may have at one time occurred, yet no evidence of a companion galaxy can be found.

On July 27, 1990, a supernova occurred near NGC 7479?s nucleus and reached a magnitude of 16. When observed in the radio band, there is a polarized jet near the bright nucleus that is unlike any other structure known. If at first you do not see a great deal of detail, relax… Allow your mind and eye time to look carefully. Even with telescopes as small as 8-10? structure can easily be seen. The central bar becomes “clumpy” and this well-studied Seyfert region is home to an abundance of molecular gas and forming stars.

Enjoy this incredible galaxy…

Friday, October 5 – Today marks the birthdate of Robert Goddard. Born 1882, Goddard is known as the father of modern rocketry – and with good reason.

In 1907, Goddard came into the public eye as a cloud of smoke erupted from the basement of the physics building in Worcester Polytechnic Institute where he had just fired a powder rocket. By 1914, he had patented the use of liquid rocket fuel and two- or three-stage solid fuel rockets. His work continued as he sought methods of putting equipment ever higher, and by 1920 he had envisioned his rockets reaching the Moon. Among his many achievements, he proved that a rocket would work in a vacuum, and by 1926 the first scientific equipment went along for the ride. By 1932, Goddard was guiding those flights and by 1937 had the motors pivoting on gimbals and controlled gyroscopically. His lifetime of work went pretty much unnoticed until the dawn of the Space Age, but in 1959 (14 years after his death) he received his acclaim at last as NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center was established in his memory.

Today in 1923, Edwin Hubble was also busy as he discovered the first Cepheid variable in M31 – the Andromeda Galaxy. Hubble’s discovery was crucial in proving that objects once classed as “spiral nebulae” were actually independent and external stellar systems like our own Milky Way.

Tonight let’s look at a Cepheid variable as we head towards Eta Aquilae, almost a fistwidth due south of bright Altair.

Discovered by Edward Pigott in 1784, Eta is a Cepheid variable star around 1200 light-years away, but its beauty can be followed easily with the unaided eye. Ranging almost a full magnitude in a period of slightly over 7 days, this yellow supergiant is 3000 times brighter than our own Sun and around 60 times larger. Watch over the days as it takes about 48 hours to achieve maximum brightness and rivals nearby Beta – then falls slowly over the next 5 days.

If you’re still out when the Moon rises, look for a conjunction with the bright planet, Jupiter! For a handful of viewers in the south-western regions of Australia, this is the universal date of an occultation event, so be sure to check resources for websites like IOTA, which will give you précises times and locations for your area.

Saturday, October 6 – Have you been watching planetary motion? On this universal date, Mars leaves the constellation of Libra and enters Scorpius. For observers in the southern hemisphere, look for a conjunction of Mercury and Saturn at dusk. While time and the stars appear to stand still and astronomical twilight begins earlier each night, let’s take one last look at Antares. It’s a relatively old, massive star – very bright and destined to end brilliantly. Or Markab – an aging blue dwarf soon to become a red giant. Now look at Deneb. It’s a supermassive blue giant shining as brightly as some globular clusters – yet fated to create another supernova remnant in Cygnus within 100 thousand years… Take a look at Enif – a spectral class K orange supergiant radiating with as much light as 7000 suns – yet it burns fast and is cooler than Sol. How about Polaris? Hotter than Sol, it’s another star about to enter a glorious retirement. Thankfully, our Sun is right in the middle of the wonderful H-R diagram!

Now wait for the Moon to rise…

Tonight it is possible to see another landing area – that of Apollo 15. Locate previous northern study crater Plato and look due south past the isolated Spitzbergen Mountains to comparably-sized Archimedes. Spend a few moments enjoying Archimedes’ well-etched terraced walls and textured bright floor. Then look east look for the twin punctuations of Aristillus and the more northern Autolycus. South of Aristillus note the heart-shape of Paulus Putredinus. There you will see Mons Hadley very well highlighted and alone on its northeastern bank. Power up to see that the Mons Hadley area includes a cove known as the Hadley Delta, and there on that plain just north of the brilliant mountain peak is where Apollo 15 touched down. Enjoy it in sunset hues!

Your first challenge for the evening will be a telescopic one known as the Hadley Rille. Using our past knowledge of Mare Serenitatis, look for the break along its western shoreline that divides the Caucasus and Apennine mountain ranges. Just south of this break is the bright peak of Mons Hadley. You’ll find this area of highest interest for several reasons, so power up as much as possible.

Impressive Mons Hadley measures about 24 by 48 kilometers at its base and reaches up an incredible 4572 meters. If this mountain was indeed caused by volcanic activity on the lunar surface, this would make it comparable to some of the very highest volcanically caused peaks on Earth, such as Mount Shasta or Mount Rainer. To its south is the secondary peak Mons Hadley Delta—the home of the Apollo 15 landing site just a breath north of where it extends into the cove created by Palus Putredinus.

Along this ridgeline and smooth floor, look for a major fault line known as the Hadley Rille, winding its way across 120 kilometers of lunar surface. In places, the rille spans 1500 meters in width and drops to a depth of 300 meters below the surface. Believed to have been formed by volcanic activity some 3.3 billion years ago, we can see the impact that lower gravity has had on this type of formation, since earthly lava channels are less than 10 kilometers long and only around 100 meters wide. During the Apollo 15 mission, Hadley Rille was visited at a point where it was only 1.6 kilometers wide—still a considerable distance as seen in respect to astronaut James Irwin and the lunar rover. Over a period of time, its lava may have continued to flow through this area, yet it remains forever buried beneath years of regolith.

Sunday, October 7 – Today celebrates the birthday of Niels Bohr. Born 1885, Bohr was a pioneer Danish atomic physicist. Why not get up early – or stay up late – to enjoy more waning Moon studies?

Journey south of landmark Eratosthenes for an area known as Sinus Aestuum – the “Bay of Billows”. Its very smooth floor is curiously riddled to the north and east by dark stains. At one time Sinus Aestuum may have been completely submerged in basaltic lava across its 290 kilometer expanse. Later the molten rock sank to the Moon’s interior before it could do much more than melt away outer layers and older surface features. However, recent studies have shown mixing in the dark mantle terrain, as well as some areas which are spectrally different – dominated by what could be crystallized beads.

While at lower powers Sinus Aestuum seems to have very little to keep your interest, try magnifying and really take a look. Just to the southwest of Eratosthenes are the wonderful ruins of crater Stadius. This one is a real ghost! Stadius was form in the lower Imbrian period, so it’s not really that old, but the lava flow of Mare Insularum has pretty much taken it over. Very little remains that can be measured of its wall, but there are enough to throw some shadows to the northeast, and you can see the vague outline of companion crater Stadius A to the west. Look for all kinds of little craterlets dotting the floor; especially resolvable is Stadius K to the south and Stadius L, which appears lengthened to the southwest.

While you travel across the plains of Sinus Aestuum, look for the Rimae Bode and area which may be lighter because it contains a mixing of volcanic glasses and black beads. Crater Bode is nothing more than the tiny dark well along the eastern shore! The long rille in the center has no name, but if the shadows allow you to follow it south, you will end in several lava dome regions that belong to crater Gambart. This is just north of the Fra Mauro region and also home to the Surveyor 2 landing area! Just a bit more south will bring you to Fra Mauro and – as craters go – 3.9 billion year old Fra Mauro is on the shallow side and spans 95 kilometers. At some 730 meters deep, standing at the foot of one of its walls would be like standing at the bottom of the Grand Canyon… Yet, time has so eroded this crater that its west wall is completely missing and its floor is covered with fissures. Even though ruined Fra Mauro seems like a forbidding place to land a manned mission, it remained high on the priority list because it is geologically rich. Ill-fated Apollo 13 was to land in a formation north of the crater which was formed by ejecta belonging to the Imbrium Basin – material which had already been mapped telescopically. By returning samples of this material from deep within the Moon’s crust, scientists would have been able to determine the exact time these changes came about. As you view Fra Mauro tonight, picture yourself in a lunar rover traversing this barren landscape and viewing the rocks thrown out from a long-ago impact. How willing would you be to take on the vision of others and travel to another world?

Until next week? Ask for the Moon, but keep on reaching for the stars!

Lunar Image Courtesy of Mike Romine.

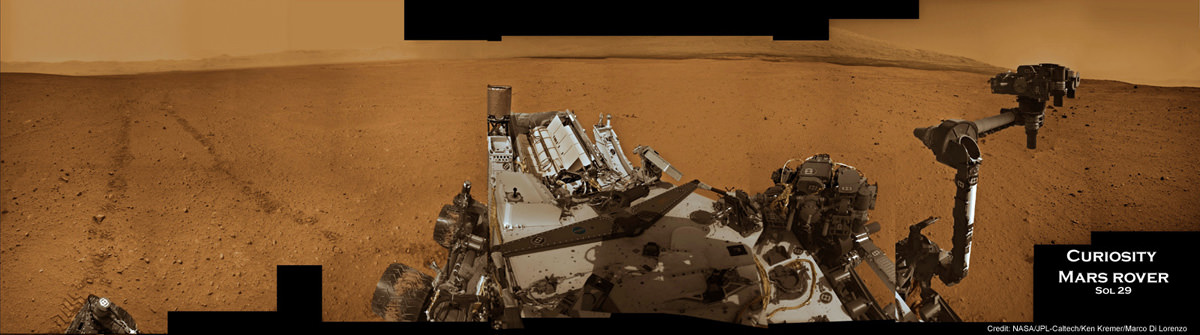

![692089main_Grotzinger-1-pia16156-43_800-600[1]](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/692089main_Grotzinger-1-pia16156-43_800-6001-580x435.jpg)