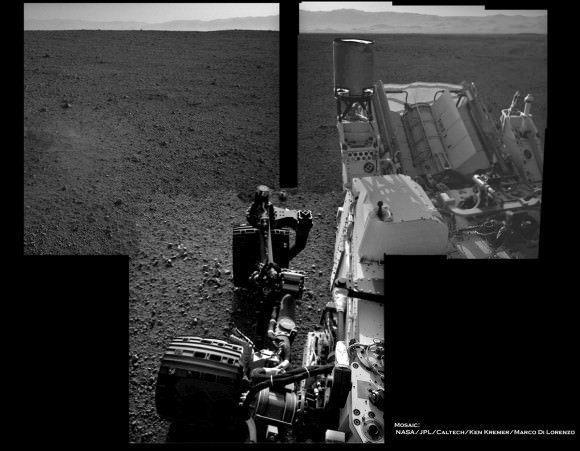

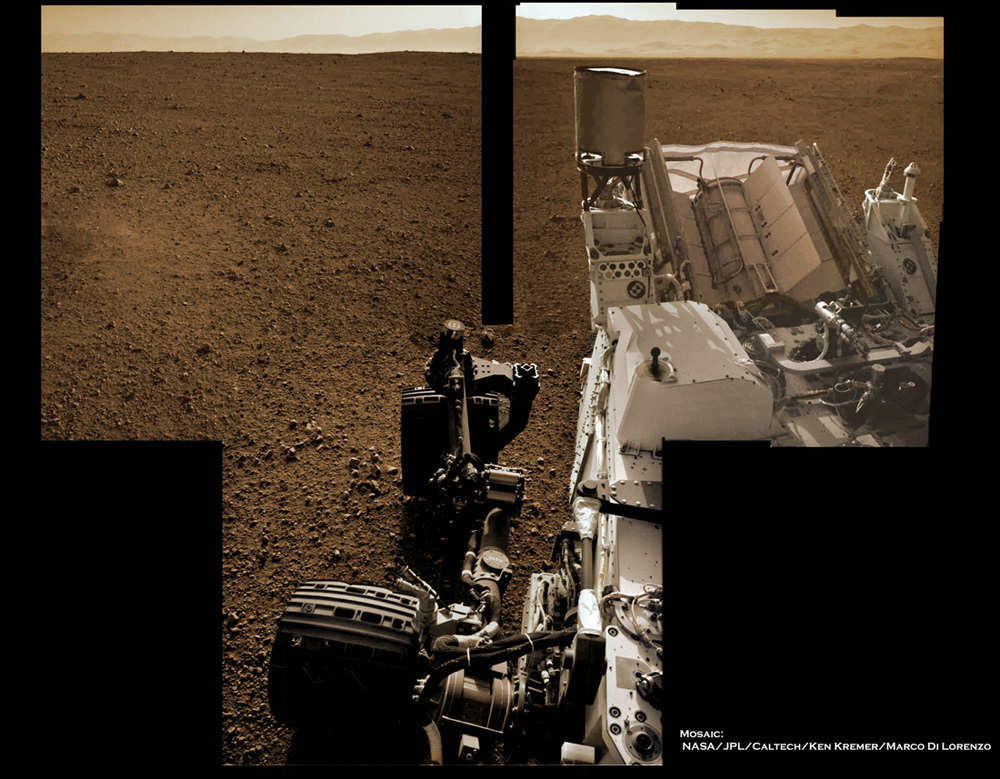

Image Caption: Curiosity’s Wheels Set to Rove soon Mars inside Gale Crater after ‘brain transplant’. This colorized mosaic shows Curiosity wheels, nuclear power source and pointy low gain antennea (LGA) in the foreground looking to the eroded northern rim of Gale Crater in the background. The mosaic was assembled from full resolution Navcam images snapped by Curiosity on Sol 2 on Aug. 8. Image stitching and processing by Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo. see black & white version below. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Ken Kremer/Marco Di Lorenzo

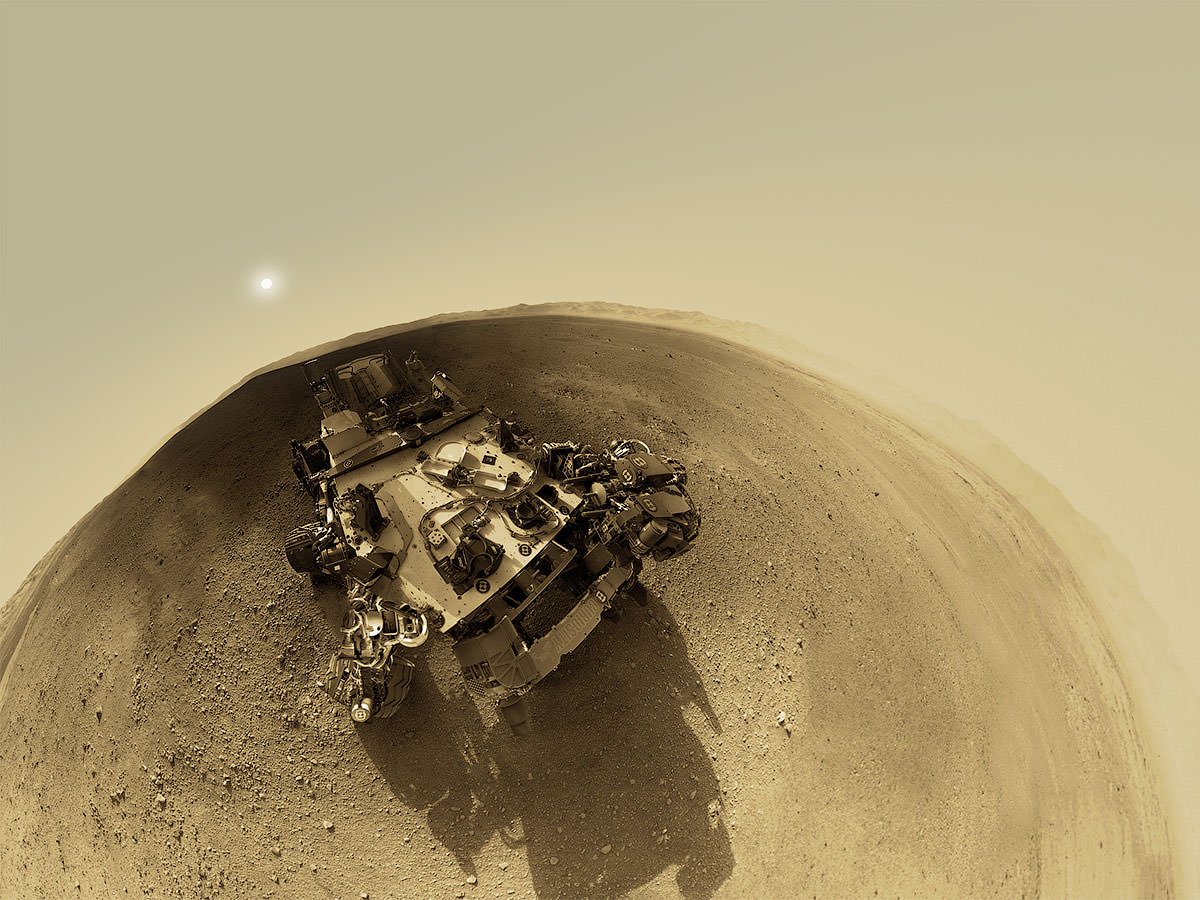

Curiosity’s weekend “Brain transplant” proceeded perfectly and she’ll be ready to drive across the floor of Gale Crater in about a week, said the projects mission managers at a NASA news briefing on Tuesday, Aug. 14. And the team can’t wait to get Curiosity’s 6 wheels mobile on the heels of a plethora of science successes after just a week on Mars.

Over the past 4 sols, or Martian days, engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) successfully uploaded the new “R10” flight software that is required to carry out science operations on the Red Planet’s surface and transform the car-sized Curiosity from a landing vehicle into a fully fledged rover.

The step by step flight software transition onto both the primary and backup computers “went off without a hitch”, said mission manager Mike Watkins of JPL at the news briefing. “We are ‘Go’ to continue our checkout activities on Sol 9 (today).”

Watkins added that the electronic checkouts of all the additional science instruments tested so far, including the APXS, DAN and Chemin, has gone well. Actual use tests are still upcoming.

“With the new flight software, we’re now going to test the steering actuators on Sol 13, and then we are going to take it out for a test drive here probably around Sol 15,” said Watkins . “We’re going to do a short drive of a couple of meters and then maybe turn and back up.”

See our rover wheel mosaic above, backdropped by the rim of Gale Crater some 15 miles away.

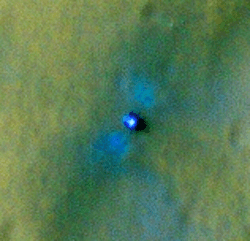

Image Caption: Curiosity landed within Gale Crater near the center of the landing ellipse. The crater is approximately the size of Connecticut and Rhode Island combined. This oblique view of Gale, and Mount Sharp in the center, is derived from a combination of elevation and imaging data from three Mars orbiters. The view is looking toward the southeast. Mount Sharp rises about 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers) above the floor of Gale Crater. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/MSSS

Curiosity made an unprecedented pinpoint landing inside Gale Crater using the rocket powered “Sky Crane” descent stage just a week ago on Aug. 5/6 and the team is now eager to get the huge rover rolling across the Martian plains towards the foothills of Mount Sharp, about 6 miles (10 km) away as the Martian crow flies.

“We have a fully healthy rover and payload,” said Ashwin Vasavada, Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) deputy project scientist. “We couldn’t be happier with the success of the mission so far. We’ve never had a vista like this on another planet before.”

“In just a week we’ve done a lot. We’ve taken our 1st stunning panorama of Gale crater with focusable cameras, 1st ever high energy radiation measurement from the surface, the 1st ever movie of a spacecraft landing on another planet and the 1st ground images of an ancient Martian river channel.”

A high priority is to snap high resolution images of all of Mount Sharp, beyond just the base of the 3.4 mile (5.5 km) tall mountain photographed so far and to decide on the best traverse route to get there.

“We will target Mount Sharp directly with the mastcam cameras in the next few days,” said Watkins.

Climbing the layered mountain and exploring the embedded water related clays and sulfate minerals is the ultimate goal of Curiosity’s mission. Scientists are searching for evidence of habitats that could have supported microbial life.

Curiosity will search for the signs of life in the form of organic molecules by scooping up soil and rock samples and sifting them into analytical chemistry labs on the mobile rovers’ deck.

Vasavada said the team is exhaustively discussing which terrain to visit and analyze along the way that will deliver key science results. He expects it will take about a year or so before Curiosity arrives at the base of Mount Sharp and begins the ascent in between the breathtaking mesas and buttes lining the path upwards to the sedimentary materials.

Watkins and Vasavada told me they are confident they will find a safe path though the dunes and multistory tall buttes and mesas that line the approach to and base of Mount Sharp.

“Curiosity can traverse slopes of 20 degrees and drive over 1 meter sized rocks. The team has already mapped out 6 potential paths uphill from orbital imagery.”

“The science team and our rover drivers and really everybody are kind of itching to move at this point,” said Vasavada. “The science and operations teams are working together to evaluate a few different routes that will take us eventually to Mount Sharp, maybe with a few waypoints in between to look at some of this diversity that we see in these images. We’ll take 2 or 3 samples along the way. That’s a few weeks work each time.”

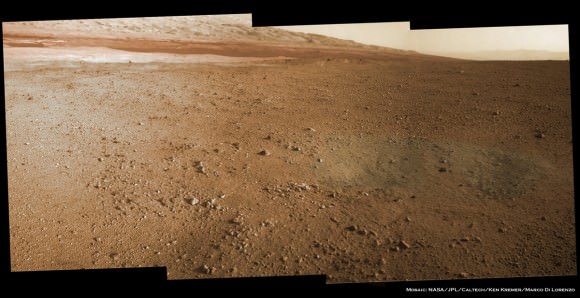

Caption: Destination Mount Sharp. This image from NASA’s Curiosity rover looks south of the rover’s landing site on Mars towards Mount Sharp. Colors have been modified as if the scene were transported to Earth and illuminated by terrestrial sunlight. This processing, called “white balancing,” is useful for scientists to be able to recognize and distinguish rocks by color in more familiar lighting. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

“We estimate we can drive something like a football field a day once we get going and test out all our driving capabilities. And if we’re talking about a hundred football fields away, in terms of 10 kilometers or so, to those lower slopes of Mount Sharp, that already is a hundred days plus.”

“It’s going to take a good part of a year to finally make it to these sediments on Mount Sharp and do science along the way,” Vasavada estimated.

The 1 ton mega rover Curiosity is the biggest and most complex robot ever dispatched to the surface of another planet and is outfitted with a payload of 10 state of the art science instruments weighing 15 times more than any prior roving vehicle.

Image Caption: Curiosity’s Wheels Set to Rove soon Mars inside Gale Crater. This mosaic shows Curiosity wheels, nuclear power source and pointy low gain antennea (LGA) in the foreground looking to the eroded northern rim of Gale Crater in the background. The mosaic was assembled from full resolution Navcam images snapped by Curiosity on Sol 2 on Aug. 8. Image stitching and processing by Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Ken Kremer/Marco Di Lorenzo – www.kenkremer.com

Image Caption: Mosaic of Mount Sharp inside Curiosity’s Gale Crater landing site. Gravelly rocks are strewn in the foreground, dark dune field lies beyond and then the first detailed view of the layered buttes and mesas of the sedimentary rock of Mount Sharp. Topsoil at right was excavated by the ‘sky crane’ landing thrusters. Gale Crater in the hazy distance. This mosaic was stitched from three full resolution Navcam images returned by Curiosity on Sol 2 (Aug 8) and colorized based on Mastcam images from the 34 millimeter camera. Processing by Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Ken Kremer/Marco Di Lorenzo

![658680main_pia15686-43_1024-768[1]](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/658680main_pia15686-43_1024-7681-580x435.jpg)