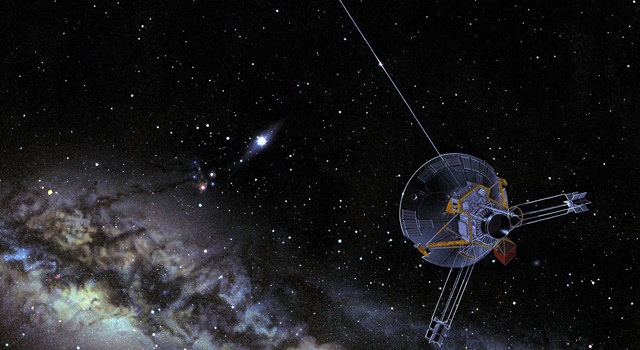

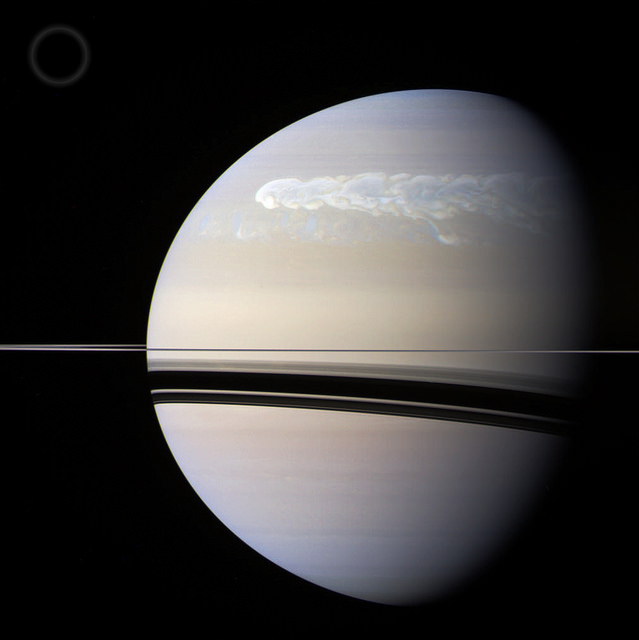

Caption: An artist’s view of a Pioneer spacecraft heading into interstellar space. Both Pioneer 10 and 11 are on trajectories that will eventually take them out of our solar system. Image credit: NASA

The case of the Pioneer Anomaly has intrigued and perplexed scientists, engineers and the space-savvy public since 1980, when analysis of tracking data from the twin Pioneer spacecraft showed a small, unexplained slowing of the duo. The answer to this puzzle — now firmly found — lies not in weird physics or mysterious dark matter, but simply the effect of heat pushing back on the spacecraft – heat from the spacecraft itself, emanating from electrical current flowing through instruments and the thermoelectric power supply.

If you’re thinking, “hasn’t this mystery been solved before?” – you’d be right.

Slava Turyshev from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory has laboriously worked on the project since 2004, recovering files from back corners of NASA closets and boxes that were on their way to the trash, converting 1970s punch card data to today’s digital format, and poring over all the data that the spacecraft have beamed back to Earth from billions of miles away.

Along the way, Turyshev has published a couple of papers on his work (here’s one from 2011), and in April of this year, The Planetary Society – who was supporting in part Turyshev’s research – claimed victory that the Pioneer Anomaly was solved.

But now, Turyshev has officially published his findings in the journal Physical Review Letters, and JPL saw fit to put out a press release.

However, over the years other scientists figured out that the culprit might be the heat coming from the spacecraft’s components. In 2001, for example, a scientist named Louis K. Sheffer published a paper, “Conventional Forces can Explain the Anomalous Acceleration of Pioneer 10” and with some good number crunching, determined that “non-isotropic radiation of spacecraft heat” could account for the slowing and “that the entire effect can be explained without the need for new physics.”

Why Sheffer’s paper wasn’t considered more seriously is uncertain, but perhaps at that time the “new physics” idea – that we may have to revise our understanding of gravitational physics — was more intriguing than a mundane effect like heat from the spacecraft’s systems.

But nonetheless, it appears everyone is satisfied with the explanation dutifully resolved by Turyshev and his team of mostly volunteer helpers. And Turyshev’s description of the effect is beautiful in its simplicity:

“The effect is something like when you’re driving a car and the photons from your headlights are pushing you backward,” he said. “It is very subtle.”

Launched in 1972 and 1973 respectively, Pioneer 10 and 11 are still heading on an outward trajectory from our Sun. In the early 1980s, navigators saw a deceleration on the two spacecraft, in the direction back toward the Sun, as the spacecraft were approaching Saturn. They dismissed it as the effect of small amounts of leftover propellant still in the fuel lines. But by 1998, as the spacecraft kept traveling on their journey and were over 13 billion kilometers (8 billion miles) away from the Sun, a group of scientists led by John Anderson of JPL realized there was an actual deceleration of about 300 inches per day squared (0.9 nanometers per second squared). They were the ones who raised the possibility that this could be some new type of physics that contradicted Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

After that, all sorts of theories surfaced, some fairly wacky, some more serious.

In 2004, Turyshev decided to really dig into the matter and started gathering records stored all over the country to analyze the data to see if he could definitively figure out the source of the deceleration. In part, according to JPL, Turyshev and his colleagues were contemplating a deep space physics mission to investigate the anomaly, and he wanted to be sure there was one before asking NASA for a spacecraft.

And so they went searching for Doppler data, telemetry data, and anything they could find about the spacecraft, including picking the brains of navigators who worked with the spacecraft over the years.

They collected more than 43 gigabytes of data, which may not seem like a lot now, but is quite a lot of data for the 1970s. He also managed to save a vintage tape machine that was about to be discarded, so he could play the magnetic tapes. Viktor Toth from Canada, heard about the effort and helped create a program that could read the telemetry tapes and clean up the old data.

They saw that what was happening to Pioneer wasn’t happening to other spacecraft, mostly because of the way the spacecraft were built. For example, the Voyager spacecraft are less sensitive to the effect seen on Pioneer, because its thrusters align it along three axes, whereas the Pioneer spacecraft rely on spinning to stay stable.

Turyshev and his colleagues were able to calculate the heat put out by the electrical subsystems and the decay of plutonium in the Pioneer power sources, which matched the anomalous acceleration seen on both Pioneers.

“The story is finding its conclusion because it turns out that standard physics prevail,” Turyshev said. “While of course it would’ve been exciting to discover a new kind of physics, we did solve a mystery.”

Turyshev’s paper: Finding the Origin of the Pioneer Anomaly.

Source: JPL

As we can see today, that wasn’t the case.

As we can see today, that wasn’t the case.