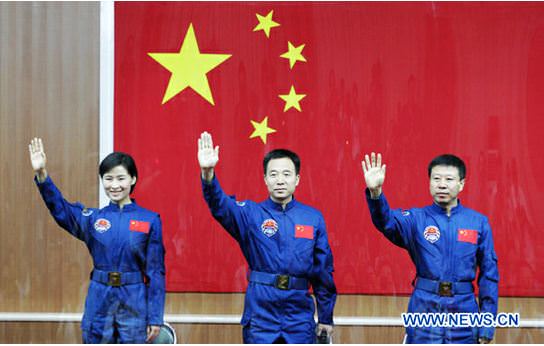

China will launch a three-person crew on Saturday, June 16, 2012 at 10:37 UTC (6:37 a.m. EDT) on board a Shenzhou 9 spacecraft, heading to the Tiangong 1 spacelab. The crew includes Liu Yang, the first female Chinese taikonaut. With her will be Jing Haipeng, the commander and a veteran of two other spaceflights and Liu Wang. This will be the first manned docking to the Tiangong 1 (Heavenly Palace), which was launched in September 2011.

The Shenzhou 9 will launch from the Jiuquan Space Launch Center in the Gobi desert in western China.

Yang is a 33-year-old fighter pilot and said during a broadcast interview, “From day one I have been told I am no different from the male astronauts…I believe in persevering. If you persevere, success lies ahead of you.”

Liu joined the taikonaut training program in May 2010 and was selected as a possible candidate for the docking mission after she excelled in testing, according to the Xinhua news agency.

She initially trained as a cargo pilot and has been praised for her cool handling of an incident when her jet hit a flock of pigeons but she was still able to land the heavily damaged aircraft.

At a press conference, the three taikonauts were behind a glass wall before a small group of hand-picked journalists. They said the manual docking was a “huge test,” but that they had rehearsed the procedure more than 1,500 times.

“The three of us understand each other tacitly. One glance, one facial expression, one movement, we understand each other thoroughly,” said Jing.

Once Shenzhou 9 reaches the vicinity of Tiangong 1, the crew will perform a manual docking, but the Chinese space agency has said future missions will have automated dockings.

Some reports have indicated the Shenzhou spacecraft is designed with a common docking system that would allow it to dock with the International Space Station in the future should China be invited to visit.

Once on board the Taingong 1, the crew will do some medical research and conduct other research including monitoring live butterflies and butterfly eggs and pupae.

China has said they hope to add more modules to their space station, with a final version of it built by 2020. A white paper released last December outlining China’s ambitious space program said the country “will conduct studies on the preliminary plan for a human lunar landing.”

Lead image caption: China’s astronauts Jing Haipeng (C), Liu Wang (R) and Liu Yang meet with media in Jiuquan, China on June 15, 2012. The three astronauts will board Shenzhou-9 spacecraft on Saturday for China’s first manned space docking mission. Credit: Xinhua/Wang Jianmin

Second image caption: An artists rendering of the Tiangong-1 module, the first part of China’s space station. To the right is a Shenzhou spacecraft, preparing to dock with the module. Image Credit: CNSA

Sources: PeopleDaily, AFP, SpaceRef.