[/caption]

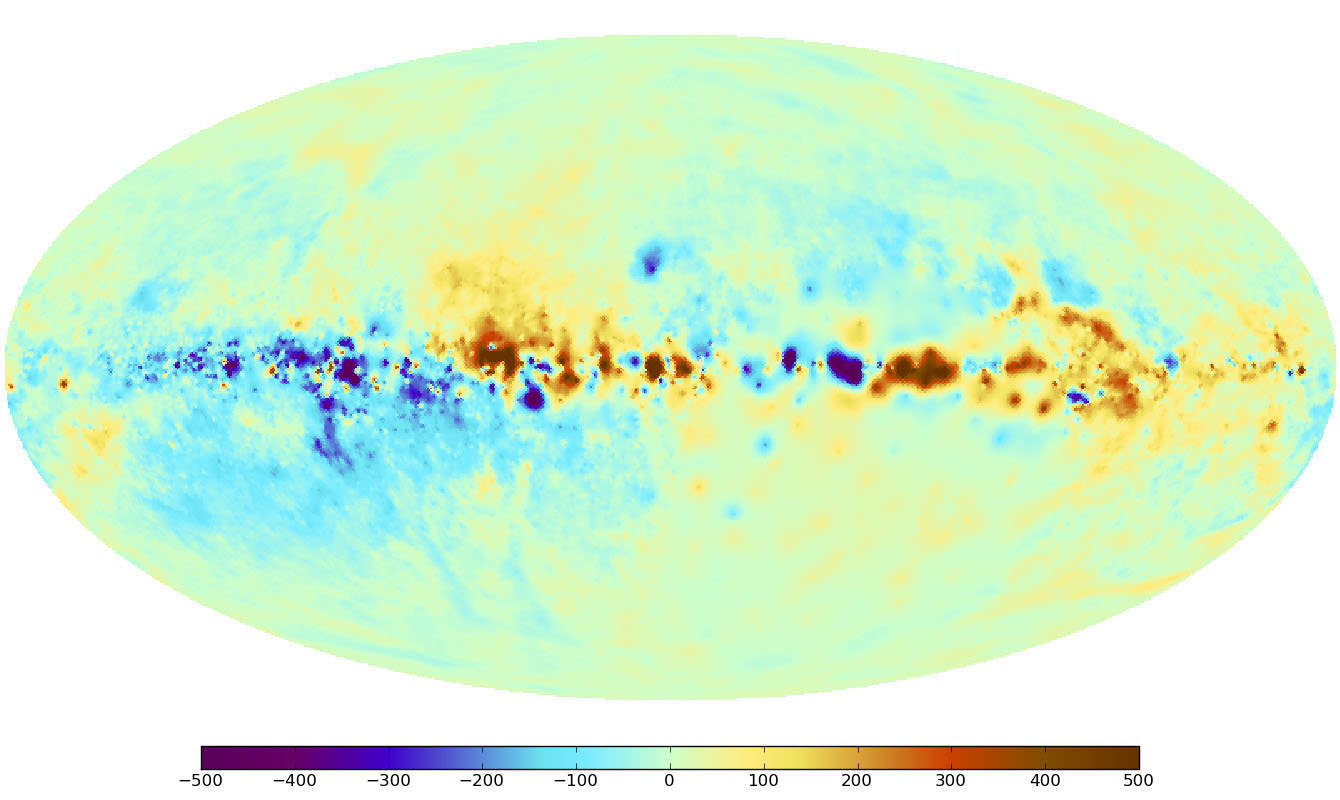

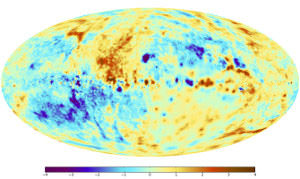

Recently we took a look at a very unusual type of map – the Faraday Sky. Now an international team of scientists, including those at the Naval Research Laboratory, have pooled their information and created one of the most high precision maps to date of the Milky Way’s magnetic fields. Like all galaxies, ours has a magnetic “personality”, but just where these fields come from and how they are created is a genuine mystery. Researchers have always simply assumed they were created by mechanical processes like those which occur in Earth’s interior and the Sun. Now a new study will give scientists an even better understanding about the structure of galactic magnetic fields as seen throughout our galaxy.

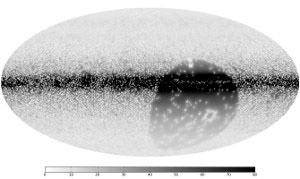

The team, led by the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics (MPA), gathered their information and compiled it with theoretical simulations to create yet another detailed map of the magnetic sky. As NRL’s Dr. Tracy Clarke, a member of the research team explains, “The key to applying these new techniques is that this project brings together over 30 researchers with 26 different projects and more than 41,000 measurements across the sky. The resulting database is equivalent to peppering the entire sky with sources separated by an angular distance of two full moons.” This huge amount of data provides a new “all-sky” look which will enable scientists to measure the magnetic structure of the Milky Way in minute detail.

The concept of the Faraday effect isn’t new. Scientists have been observing and measuring these fields for the last century and a half. Just how is it done? When polarized light passes through a magnetized medium, the plane of the polarization flips… a process known as Faraday rotation. The amount of rotation shows the direction and strength of the field and thereby its properties. Polarized light is also generated from radio sources. By using different frequencies, the Faraday rotation can also be measured in this alternative way. By combining all of these unique measurements, researchers can acquire information about a single path through the Milky Way. To further enhance the “big picture”, information must be gathered from a variety of sources – a need filled by 26 different observing projects that netted a total of 41,330 individual measurements. To give you a clue of the size, that ends up being about one radio source per square degree of sky!

Thanks to an algorithm crafted by the MPA, scientists are able to face these types of difficulties with confidence as they put together the images. The algorithm, called the “extended critical filter,” employs tools from new disciplines known as information field theory – a logical and statistical method applied to fields. So far it has proven to be an effective method of weeding out errors and has even proven itself to be an asset to other scientific fields such as medicine or geography for a range of image and signal-processing applications.

Even though this new map is a great assistant for studying our own galaxy, it will help pave the way for researchers studying extragalactic magnetic fields as well. As the future provides new types of radio telescopes such as LOFAR, eVLA, ASKAP, MeerKAT and the SKA , the map will be a major resource of measurements of the Faraday effect – allowing scientists to update the image and further our understanding of the origin of galactic magnetic fields.

Original Story Source: Naval Research Laboratory News.