[/caption]

Editor’s note: Dr. David Warmflash, principal science lead for the US team from the LIFE experiment on board the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft, provides an update on the mission for Universe Today.

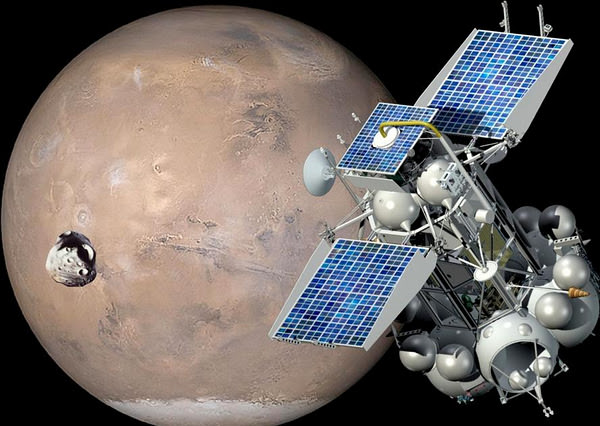

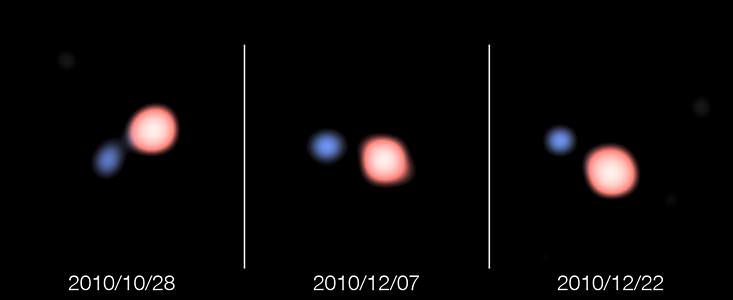

Russia’s Phobos-Grunt spacecraft is in no better position than it was a month ago, when it reached low Earth orbit on November 9 yet failed to ignite the upper stage engine that was to propel it to Phobos, the larger of Mars’ two small moons. Indeed, with an orbit measuring 204.823 kilometers at perigee (the low point) and 294.567 kilometers at apogee as of today, the spacecraft is well on its well to a fiery reentry through Earth’s atmosphere in early January if it cannot be rescued in the intervening time. But the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, is not ready to give up on the probe yet, and have asked ESA to resume trying to contact Phobos-Grunt.

Despite success in contacting Grunt and getting it to send telemetry two weeks ago using a modified antenna in Perth Australia, subsequent attempts to command the spacecraft to boost her orbit failed.

Then last week, after modifying another antenna, this one in Maspalomas on the Canary Islands, the European Space Agency (ESA) announced that efforts to track and communicate with the spacecraft would end. As a result, any remaining hope that the craft might at least be boosted to a more stable orbit to allow for diagnoses and eventual repair faded away.

But, in response to requests from the Russian Space Agency (Roscosmos), ESA now has decided to renew tracking and communications efforts from the Maspalomas station. Located off of the northwest coast of Africa, Maspalomas is well-situated with respect to Phobos-Grunt’s course around Earth. Since fewer communication attempts have been made from Maspalomas as compared with Perth, ESA and Roscosmos may be thinking that not all potential tricks to get the geometry right have been exhausted. Thus, new attempts to hail the unpiloted science probe began on Monday and will continue through Friday, December 9th. Presumably, ESA would continue to support the mission beyond Friday, if anything happens suggesting that Phobos-Grunt has received the instructions and is capable of responding, even in part.

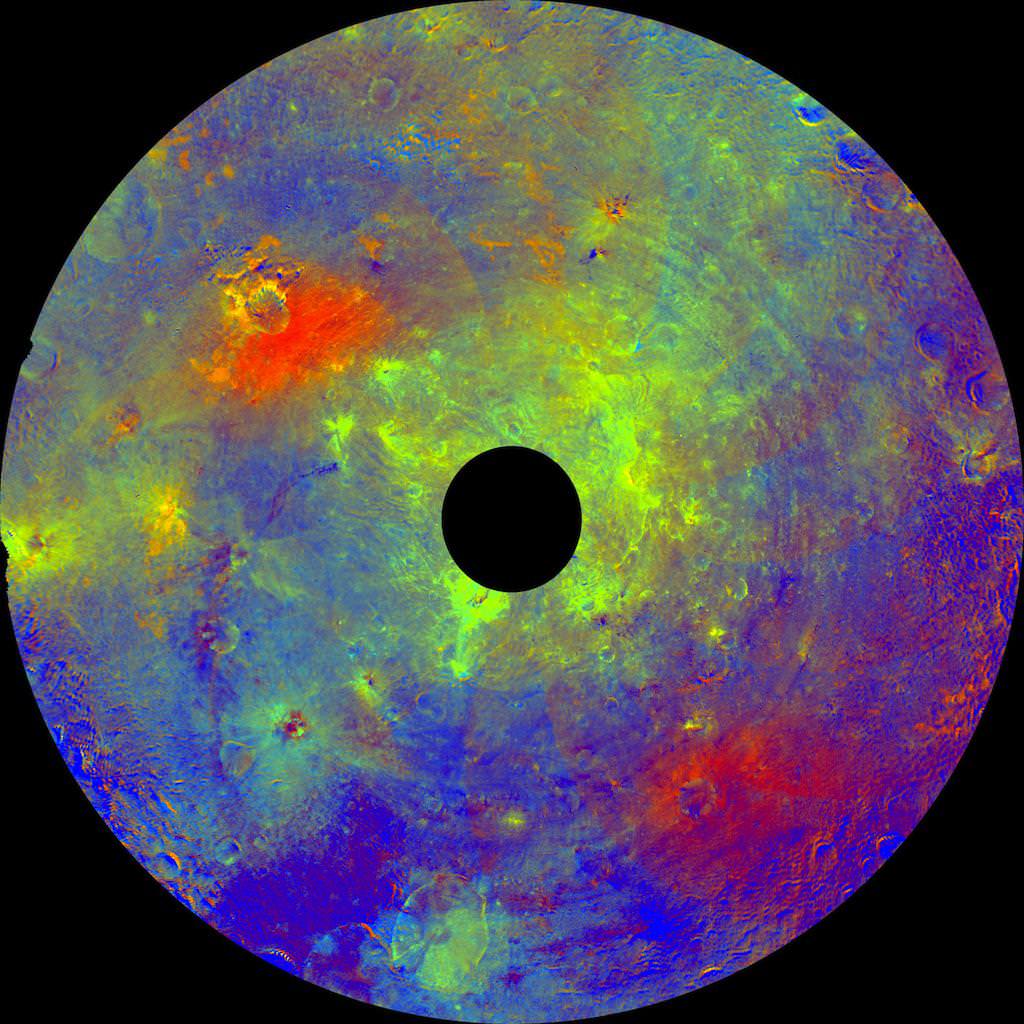

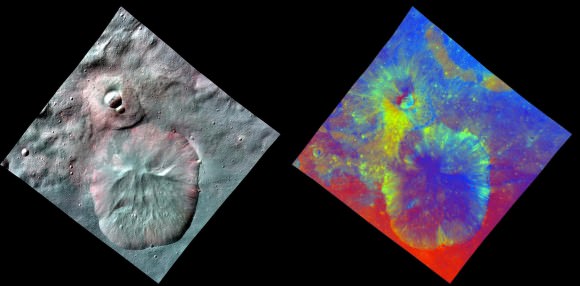

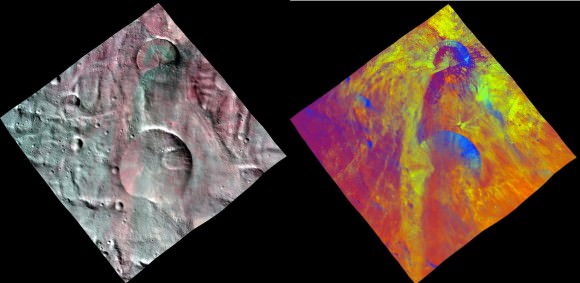

Designed to land on the surface of Phobos, the Grunt spacecraft carries about 50 kilograms of scientific equipment built to make celestial and geophysical measurements, and to conduct mineralogical and chemical analysis of the regolith (crushed rock and dust) of the tiny moon. The chemical analysis that is to be conducted includes a search for organic matter, the building material for life. Studies to be conducted on the Phobosian surface potentially could elucidate the origins of Phobos and the other Martian moon, Deimos. Additionally, the presence of organic matter on Phobos would suggest that the surface of Mars itself contains organics. Despite findings by NASA’s Viking landing crafts in the 1970s suggesting that the surface of Mars lacks organic material, studies by more recent probes suggest that compounds known as perchlorates –detected by Viking but dismissed as contaminants from Earth– may have been native to Mars. This issue will be investigated further when NASA’s Curiosity rover arrives on the Red Planet several months from now.

Grunt also carries Yinhou-1, a Chinese probe that is to orbit Mars for 2 years. After releasing Yinhou-1 into Mars orbit and landing on Phobos, Grunt is designed to launch a return capsule, carrying a 200 gram sample of regolith back to Earth. Also traveling within the return capsule is the Planetary Society’s Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment (LIFE), designed to investigate how readily living forms could spread between neighboring planets.

Although prospects for this ambitious mission still look bleak, Alexander Zakharov of Russia’s Space Research Institute, who was instrumental in getting the LIFE experiment onto the Grunt mission, has suggested that a new Grunt mission might be launched, presumably on time for the next launch window to Mars, which opens in approximately 26 months.

Meanwhile, today, NASA’s space debris chief said that Phobos-Grunt would pose no threat to Earth when it reenters the atmosphere.

Although the window for a trip to Mars is about to close, should control over Phobos-Grunt be restored, it might be kept in a higher orbit for two years, or sent to an alternate destination, such as Earth’s own Moon, or an asteroid.