Thankful Astronomer

[/caption]

Typically, I’ve been known as the Angry Astronomer. But since it’s Thanksgiving here in the US, I figured I should take a break and remind everyone that there’s a lot to be thankful for.

I’m thankful for our galaxy. Aside from being quite nice to look at, its collective (but weak) magnetic field, and the pressure from all the stars within it, protect us from the shock of plowing through the intergalactic medium as well as intergalactic cosmic rays.

I’m thankful for quantum mechanics. While it wasn’t the most fun course I’ve ever taken the fact that particles often behave as waves, giving rise to atomic orbitals, is what makes up the discreet absorption an emission spectra. Without this astronomers wouldn’t be able to determine the composition of stars from great distances.

I’m thankful for Newton’s third law; that one about equal and opposite forces and all that. It’s what lets the moon create tides. This may have had important effects in stabilizing our axial tilt and making life feasible on the planet in the first place. It’s also what allows us to detect planets around other stars through the “wobble method” and exoplanets are just cool.

I’m thankful for the immensely pristine vacuum that exists just beyond our atmosphere. Its existence allows astronomers to test theories at some of the lowest densities imaginable.

I’m thankful for neutron stars and black holes which allow astronomers to test theories at the highest densities imaginable.

I’m thankful for the supernovae which produce these objects and seed the universe with the heavy elements necessary to make planets, people, pineapples, and platypi.

I’m thankful that we’ve had the relatively close supernova (SN 1987a) to study. While I’d love to have another one in our own galaxy, I’m thankful we haven’t had one too close, or that directed a Gamma Ray Burst our way. With all the other issues we face from the universe, another Ordovician extinction just doesn’t sound too fun.

I’m thankful for dark matter. It may be a huge headache for astronomers trying to figure out what it is, but even if we can’t see it, it’s still like the Force: It binds the galaxies together.

I’m thankful for the Sun. Its nearly 1400 watts per square meter pours energy onto our planet, making all life possible, Creationist claims and ignorance aside.

I’m thankful for our atmosphere. It’s generally pretty breathable and it does a great job of blocking out that cancer causing UV. If only it would lighten up and let some more IR through so we didn’t have to send telescopes to space to study this region of the spectrum.

I’m thankful for this lump of rock, third from the Sun, we’re all riding on. It the grand scheme of things, it’s just a pale blue dot, but that’s home. And it’s not so bad.

So what is everyone else thankful for?

How Will MSL Navigate to Mars? Very Precisely

Getting the Mars Science Laboratory to the Red Planet isn’t as easy as just strapping the rover on an Atlas V rocket and blasting it in the general direction of Mars. Spacecraft navigation is a very precise and constant science, and in simplest terms, it entails determining where the spacecraft is at all times and keeping it on course to the desired destination.

And, says MSL navigation team chief Tomas Martin-Mur, the only way to accurately get the Curiosity rover to Mars is for the spacecraft to constantly be looking in the rearview mirror at Earth.

“What we do is ‘drive’ the spacecraft using data from the Deep Space Network,” Martin–Mur told Universe Today. “If you think about it, we never see Mars. We don’t have an optical navigation camera or any other instruments to be able to see or sense Mars. We are heading to Mars, all the while looking back to Earth, and with measurements from the Earth we are able to get to Mars with a very high accuracy.”

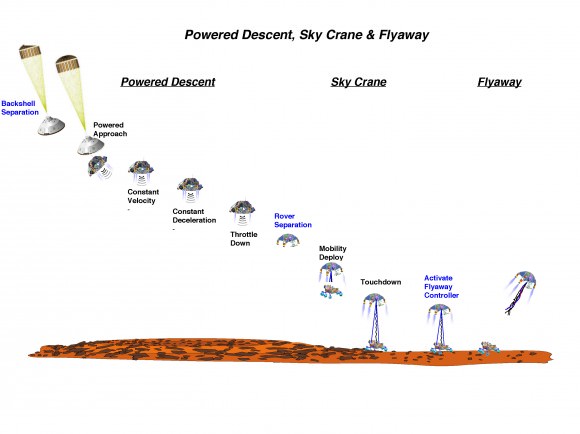

This high accuracy is very important because MSL is using a new entry, descent and landing guidance system which will allow the spacecraft to land more precisely than any previous landers or rovers.

“It is very challenging, and even though it is something similar to what we have done before with the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission, this time it will be done at an even higher level of precision,” Martin-Mur said. “That allows us to get to a very exciting place, Gale Crater.”

On Earth, we constantly can find exactly where we are with GPS – which is on our cell phones and navigation equipment. But there is no GPS at Mars, so the only way the rover will be able to head to –and through — a precise point in the Red Planet’s atmosphere is for the navigation team to know exactly where the spacecraft is and for them to keep telling the spacecraft exactly where it is. They use the Deep Space Network (DSN) for those determinations from launch, all the way to Mars.

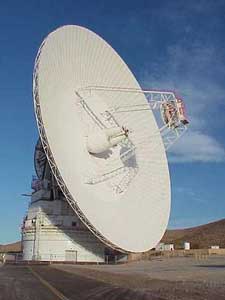

The Deep Space Network consists of a network of extremely sensitive deep space communications antennas at three locations: Goldstone, California; Madrid, Spain; and Canberra, Australia. The strategic placement approximately 120 degrees apart on Earth’s surface allows constant observation of spacecraft as the Earth rotates.

But of course, it’s not as easy as just getting the rocket from Point A to Point B since Earth and Mars are not fixed positions in space. Navigators must meet the challenges of calculating the exact speeds and orientations of a rotating Earth, a rotating Mars, as well as a moving, spinning spacecraft, while all are simultaneously traveling in their own orbits around the Sun.

There are other factors like solar radiation pressure and thruster firings that all have to be precisely calculated.

Martin-Mur said even though MSL is a much bigger rover with a bigger spacecraft and backshell than the MER mission, the navigation tools and calculations aren’t much different. And in some ways, navigating MSL might be easier.

“The Atlas V vehicle provides a much more precise launching and can put us in a more precise path than the MER, which used a Delta II,’ Martin-Mur said. “This allows us to use less propellant, proportionally per pound, to get to Mars than the MER rovers did.”

The MER rovers and spacecraft weighed about 1 ton, while MSL weighs almost 4 tons. MSL is allotted 70 kg of propellant for the cruise stage, while the MER rovers each used about 42 kg of propellant.

Interestingly, for the MSL spacecraft to descend through Mars’ atmosphere and land, the spacecraft will use about 400 kg of propellant.

Additionally, Martin-Mur said more precise planetary ephemeris and Very Long Baseline Interferometry measurements are available, enabling the navigation to be able to deliver the spacecraft to the right place in the atmospheric entry interface, so the vehicle finds itself in the range of parameters that it has been designed to operate.

Navigation at Launch

It all starts with years of preparations and calculations by the navigation team, which must calculate all the possible trajectories to Mars depending on exactly when the Atlas V rocket launches with MSL aboard.

In some cases there are literally thousands of launch opportunities and all the possible trajectories must be calculated precisely. The Juno mission, for example, had two-hour daily launch windows with 3,300 possible launch opportunities. For MSL the daily launch windows contain liftoff opportunities in 5 minutes increments. Across the 24 day launch period the team has calculated 489 different trajectories for all the possible launch opportunities.

But ultimately, they will end up using only one.

“This is not something you do on the fly – you prepare all this well in advance so you have time to sit back and assess it and check it,” said another member of the MSL navigation team, Neil Mottinger, who has worked at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory since 1967. He’s worked on navigation for many missions like Mariner, Voyager, the MER, and several international missions.

“The initial function of navigation at launch is to determine the actual spacecraft trajectory well enough so the spacecraft signal will be well within the beam-width of the DSN antennae,” Mottinger told Universe Today.

The Mars Science Laboratory will separate from the rocket that boosted it toward Mars at about 44 minutes after launch, with the navigator’s tracking the spacecraft’s every move.

Mottinger added that without the DSN’s communication capabilities, there are no planetary missions. “The Navigation team does whatever it can to make sure there aren’t any gaps in communication,” he said. “It’s crunch time during the first 6-8 hours after launch to be able to determine the exact position of the spacecraft.”

From the recent problems with the Phobos-Grunt mission, it is evident how difficult it is to track and communicate with a just-launched spacecraft.

Mid-course Corrections

Again, the navigation team has modeled and calculated all the maneuvers and thruster burns for the mission. Once MSL is on its way to Mars, the navigation team will revisit all their models and design the maneuvers to take the spacecraft to the right entry interface at Mars.

“We’ll keep doing orbit determination and re-designing the maneuvers for the spacecraft,” said Martin-Mur. “MSL has 1 lb thrusters – the same size as the MER spacecraft — but our spacecraft is almost four times heavier so the maneuvers we do take a long time – some will take hours.”

For interplanetary navigation, the engineers use distant quasars as landmarks in space for reference of where the spacecraft is. Quasars are incredibly bright, but are at such colossal distances that they don’t move in the sky like nearer background stars do. Martin-Mur provided a list of nearly 100 different quasars that could be used for this purpose, depending on where the spacecraft is.

“It is interesting,” Martin-Mur mused, “with quasars we are using something that is billions of light years away from us, from the very early universe, which are so old that they might not even be there anymore. It is really cool that we are using an object that currently may not exist anymore, but using them for very precise navigation.”

The navigation team also needs to model the solar radiation pressure – the effect the Sun’s radiation has on the spacecraft.

“We know very well, thanks to our friends from the Solar Systems Dynamics group, where Mars is going to be and where the Earth and Sun are,” said Martin-Mur. “But since this spacecraft has not been in space before, what is not known precisely is how solar radiation pressure will affect the surface properties of the spacecraft, and how it will perturb the spacecraft. If we don’t have a good model for that, we could be hundreds of kilometers off as the spacecraft goes from Earth to Mars.”

Arriving at Mars

As the spacecraft approaches Mars, it is very important to know precisely where the spacecraft is. “We need to target the spacecraft to the right entry point,” said Martin-Mur, “and tell the spacecraft where it will enter, so it will be able to find its way to the landing site.”

The MSL Entry Descent and Landing Instrumentation, or MEDLI, will stream information back to Earth as the probe enters the atmosphere, letting the navigators — and the science team – know precisely where the rover has landed.

Only then will the navigation team be able — maybe — to breathe a sigh of relief.

Does Pluto Have a Hidden Ocean?

[/caption]

In recent years, it has become surprisingly apparent that, contrary to previous belief, Earth is not the only place in the solar system with liquid water. Jupiter’s moon Europa, and possibly others, are now thought to have a deep ocean below the icy crust and even subsurface lakes within the crust itself, between the ocean below and the surface. Saturn’s moon Titan may also have a subsurface ocean of ammonia-enriched water in addition to its surface lakes and seas of liquid methane. Then of course there is another Saturnian moon, Enceladus, which seems to not only have liquid water below its surface, but huge geysers of water vapour and ice particles erupting from long fissures at its south pole, which have been sampled directly by the Cassini spacecraft. Even some asteroids may have liquid water layers beneath their surfaces. There is also still a chance that Mars might have subsurface aquifers.

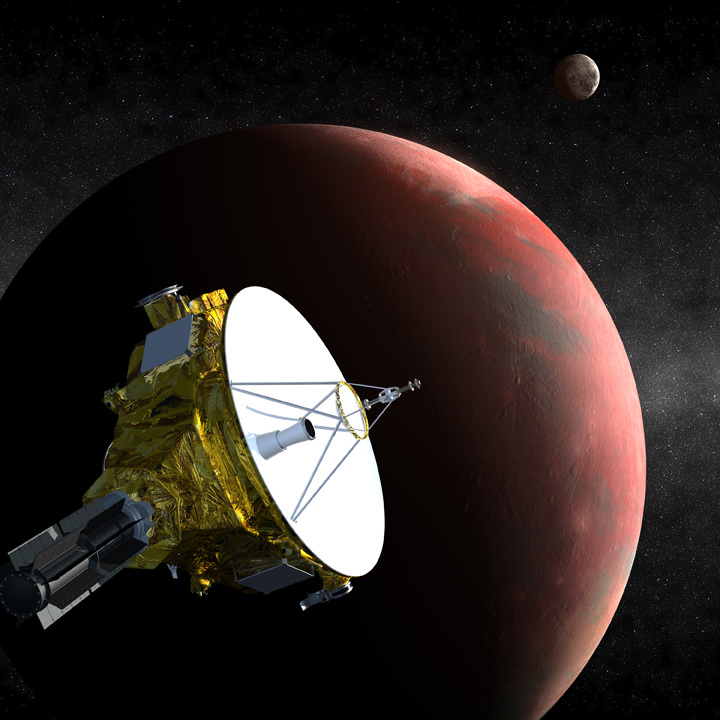

But now there is another contender which at first thought might seem to be the most unlikely place to find water – Pluto.

Inhabiting the bitterly cold, lonely outer reaches of the solar system, this dwarf planet would hardly seem to be a good place to look for liquid water, but new research is indicating that, like the other moons already mentioned, it may yet surprise us. It is now being suggested that a subsurface ocean is not only possible, but likely.

The New Horizons spacecraft is scheduled to fly by Pluto in 2015, and it may be able to confirm the existence of the ocean if it is actually there. As it is understood right now, Pluto has a thin shell of nitrogen ice covering a thicker shell of water ice. But is there a layer of liquid water below that? The way for New Horizons to help to determine that is to study the surface features and shape of Pluto as it passes. If there is a noticeable bulge toward the equator, then that means that any primordial ocean or liquid layer probably froze a long time ago, since a liquid layer would tend to cause the surface ice to flow, reducing any bulge. This is based on the fact that a spherical body, as it rotates, will push material toward the equator by angular momentum. If there is no bulge, then any liquid layer is probably still liquid today.

The surface itself can also provide clues about what lies beneath. If there are large fractures, as there are on Europa and Enceladus, their characteristics can be an indication of whether there is an ocean down below. The fractures are caused by surface stresses; tensional stresses would result from icy water beneath the outer ice shell while compressional stresses would indicate a solid layer instead. The long fractures on Europa are particularly reminiscent of the cracked ice floes in Antarctica on Earth where an ice layer covers the sea water beneath it. If geysers similar to those on Enceladus were to be seen on Pluto, that would also of course be good evidence for an ocean.

There is also, inevitably, the question of life. If Pluto’s rocky interior contains radioactive isotopes such as potassium, as seems likely, they could provide enough heat to maintain an ocean. “I think there is a good chance that Pluto has enough potassium to maintain an ocean,” said planetary scientist Francis Nimmo from the University of California at Santa Cruz, who is involved with the new studies. And if you have liquid water and heat… Pluto, however, is thought to lack organics, which would be necessary as a starting point for life.

A Plutonian ocean? Who would have ever thought? When New Horizons finally reaches Pluto in 2015, we should hopefully have a better idea one way or the other regarding this intriguing possibility.

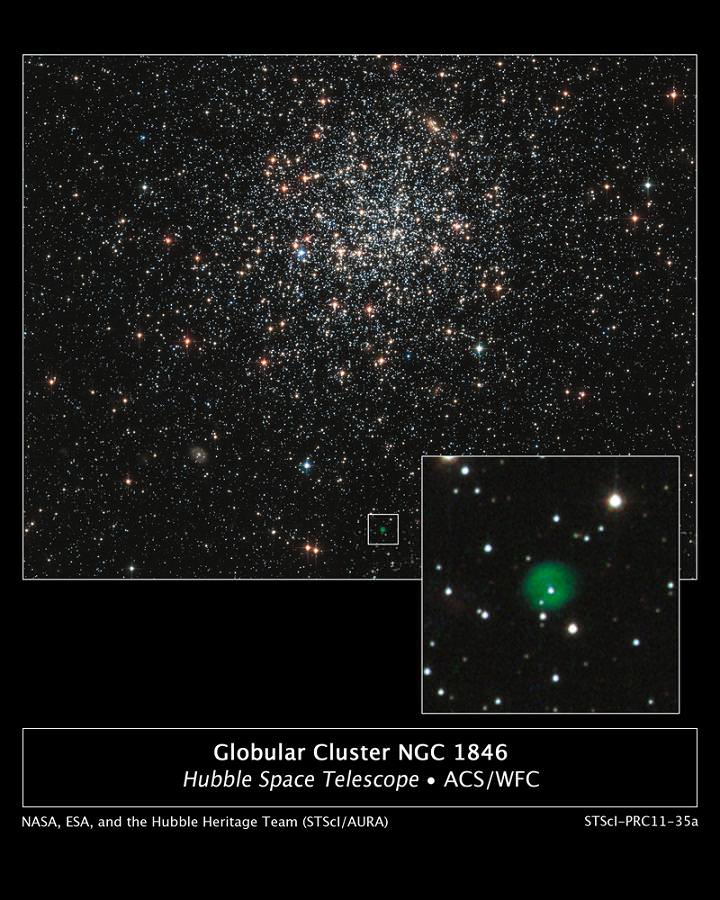

NGC 1846 – Hubble Reveals Peculiar Life And Death Of A Stellar Population

[/caption]

About 160,000 light years away in the direction of southern constellation Doradus, sits a globular cluster. It’s not a new target for the Hubble Space Telescope, but it has had a lot to say for itself over the last twelve years. It’s actually part of the Large Magellanic Cloud, but it’s no ordinary ball of stars. When it comes to age, this particular region is mighty complex…

In a 34 minute exposure taken almost a half dozen years ago, the Hubble snapped both life and death combined in an area where all stars were once assumed to be the same age. Globular clusters, as we know, are spherical collections of stars bound by gravity which orbit the halo of many galaxies. At one time, astronomers assumed their member stars were all the same age – forming into their own groups at around the same time the parent galaxy formed. But now, evidence points toward these balls of stars as having their own agenda – and may have evolved independently over the course of several hundreds of million years. What’s more, we’re beginning to learn that globular cluster formation may differ from galaxy to galaxy, too. Why? Chances are they may have encountered additional molecular clouds during their travels which may have triggered another round of star formation.

“An increasing number of photometric observations of multiple stellar populations in Galactic globular clusters is seriously challenging the paradigm of GCs hosting single, simple stellar populations.” says Giampaolo Piotto of the University of Padova, Italy. “These multiple populations manifest themselves in a split of different evolutionary sequences as observed in the cluster color-magnitude diagrams. Multiple stellar populations have been identified in Galactic and Magellanic Cloud clusters.”

However, it’s not the individual stars which make this Hubble image such a curiosity, it’s the revelation of a planetary nebula. This means a huge disparity in the member star’s ages…. one of up to 300 million years. Is it possible that the shell and remains of this dead star is a line-of-sight phenomenon, or is it truly a cluster member?

“We report on Hubble Space Telescope/ACS photometry of the rich intermediate-age star cluster NGC 1846 in the Large Magellanic Cloud, which clearly reveals the presence of a double main-sequence turn-off in this object. Despite this, the main-sequence, subgiant branch and red giant branch are all narrow and well defined, and the red clump is compact.” says A. D. Mackey and P. Broby Nielsen. ” We examine the spatial distribution of turn-off stars and demonstrate that all belong to NGC 1846 rather than to any field star population. In addition, the spatial distributions of the two sets of turn-off stars may exhibit different central concentrations and some asymmetries. By fitting isochrones, we show that the properties of the colour–magnitude diagram can be explained if there are two stellar populations of equivalent metal abundance in NGC 1846, differing in age by around 300 million years.”

So what’s wrong with the picture? Apparently nothing. The findings have been studied and studied again for errors and even “contamination” by field stars in relation to NGC1846’s main sequence turn off. It’s simply a bit of a cosmic riddle just waiting for an explanation.

“We propose that the observed properties of NGC 1846 can be explained if this object originated via the tidal capture of two star clusters formed separately in a star cluster group in a single giant molecular cloud.” concludes Mackey and Nielson. “This scenario accounts naturally for the age difference and uniform metallicity of the two member populations, as well as the differences in their spatial distributions.”

Original Story Source: NASA’s Hubble Finds Stellar Life and Death in a Globular Cluster. For Further Reading: A double main-sequence turn-off in the rich star cluster NGC 1846 in the Large Magellanic Cloud, Population Parameters of Intermediate-Age Star Clusters in the Large Magellanic Cloud. I. NGC 1846 and its Wide Main-Sequence Turnoff and Multiple stellar populations in three rich Large Magellanic Cloud star clusters.

Contact Established with Phobos-Grunt Spacecraft — Can the Mission Go On?

[/caption]

Editor’s note: Dr. David Warmflash, principal science lead for the US team from the LIFE experiment on board the Phobos-Grunt spacecraft, provides an update on the mission for Universe Today.

In an exciting development in the ongoing story of the Phobos-Grunt mission, a tracking station at Perth, Australia established contact with the Russian spacecraft on November 22 at 20:25 UT. This was the first signal received on Earth since the mission to Mars’ moon was launched on November 8, 2011.

Teams from ESA, who made the initial contact, are now working closely with engineers in Russia to determine how best to maintain communications with the spacecraft. As controllers begin the task of figuring out how to use this achievement to enable sending the spacecraft new commands, discussion is ongoing on whether the launch window will still be open for the craft to complete the mission.

The hopes are now is that at the very least engineers can prevent the spacecraft from plummeting back to Earth – and with guarded optimism that the mission could proceed in some manner.

Before contact was made, some reports said that if contact was made by November 24, the mission could proceed as planned, while other experts were saying that the launch window to complete the sample return mission closed on November 21.

But yet, a mission leaving from Earth orbit well into December might still succeed.

Built to travel to Phobos, the larger of Mars’ two moons, the centerpiece of the unmanned spacecraft is a small capsule in which 200 grams of regolith (surface material consisting of dust and crushed rock) is to make a return flight to Earth. To launch the capsule on a flight that would return it to Earth in 2014, the spacecraft was scheduled to land on Phobos in February 2013 after entering orbit around Mars in October 2012.

A launch window is a period during which travel from one celestial body to another is possible, given a spacecraft’s propulsion capabilities and the alignment of the celestial bodies as they move through space. In the future, advanced propulsion technologies could allow for trips between Earth and Mars to depart at any time, but for now spacecraft must wait for the optimal moment. For trajectories from Earth to Mars, launch windows occur roughly every 26 months, as do launch windows for inbound flights to Earth from Mars.

The launch window for an Earth-to-Mars trajectory actually would allow Grunt to reach Mars and Phobos, if the spacecraft is readied for departure within two or three weeks from today. In such a case, however, the collection of regolith on the Phobosian surface would take place after that window has closed for the capsule to launch back to Earth. This is why people are saying that the window for Phobos-Grunt will close this Thursday.

But, as stated earlier, the window could still be open through mid-December. To see why, let’s take a glimpse of the Grunt’s science payload and other components . Sitting in front of what the Russian Space Agency is calling the sustainer engine, whose job is to propel the spacecraft from Earth to Mars, is a 110 kilogram probe called Yinhuo-1. China’s first Mars probe, Yinhuo-1 is to orbit the Red Planet for two years, performing various scientific studies. Moving forward from Yinhuo-1, brings us to the interplanetary module, Grunt’s descent stage.

Costing 5 billion rubles, or about 160 million US dollars, the interplanetary module is equipped with a descent engine and legs for landing on the Martian moon, machinery for scooping the regolith sample, and about 50 kilograms of extremely advanced scientific equipment whose value to the mission does not depend on whether the regolith sample makes it back to Earth.

Finally, there is the ascent stage and the return capsule that will lift off with it for the flight to Earth. In addition to accommodating the regolith that will be deposited inside, the capsule holds the Planetary Society’s LIFE biomodule, a study of the effects of the interplanetary space environment on organisms during a long-term voyage through space.

Before and after the departure of the return capsule, the instruments of the interplanetary module will be at work, performing celestial measurements, studying solar wind, and conducting geophysical studies -experiments whose results will help planetary scientists to understand the origin of our Solar System. The science package also will perform elemental, chemical, mineralogical, and thermal analysis of the regolith, look for traces of gases from Mars, and search for organic matter, the stuff of life.

If Grunt were to make a one-way trip to Phobos, all of these studies could be performed, while Yinghuo-1 could be deployed around Mars, as is supposed to happen during a round-trip voyage. If it were determined that the capsule really had no chance of making it from Phobos back to Earth, the capsule might even be jettisoned in high Earth orbit before the sustainer stage completes the final burn to escape Earth’s gravitational pull. This might return the LIFE biomodule to Earth after a long trajectory through deep space that would satisfy the objectives of the experiment. Then, we could recover our biomodule and study the organisms as planned.

On the other hand, controllers might consider sending the return capsule to Phobos despite the closure of the launch window for a return flight. After landing on the Martian moon atop the interplanetary module, the ascent stage need only wait until the next launch window opens 26 months later for arrival on Earth in 2016.

The contact now made with the spacecraft may open up even more possibilities for saving the mission. ESA said in a press release that the signals sent to Phoboos-Grunt commanded the spacecraft’s transmitter to switch on, sending a signal down to the station’s 15 m dish antenna.

Data received from Phobos-Grunt were then transmitted from Perth to Russian mission controllers via ESA’s Space Operations Centre, Darmstadt, Germany, for analysis.

Additional communication slots are available on November 23 at 20:21–20:28 GMT and 21:53–22:03 GMT, and ESA teams are working closely with Russian controllers to determine how best to maintain communication with their spacecraft.

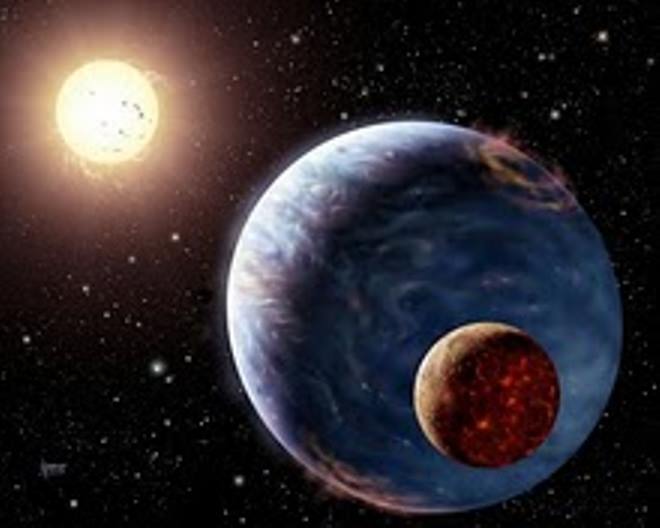

Planetary Habitability Index Proposes A Less “Earth-Centric” View In Search Of Life

[/caption]

It’s a given. It won’t be long until human technology will expand our repertoire of cataloged exoplanets to astronomical levels. Of these, a huge number will be considered within the “habitable zone”. However, isn’t it a bit egotistical of mankind to assume that life should be “as we know it”? Now astrobiologists/scientists like Dirk Schulze-Makuch with the Washington State University School of Earth and Environmental Sciences and Abel Mendez from the University of Puerto Rico at Aricebo are suggesting we take a less limited point of view.

“In the next few years, the number of catalogued exoplanets will be counted in the thousands. This will vastly expand the number of potentially habitable worlds and lead to a systematic assessment of their astrobiological potential. Here, we suggest a two-tiered classification scheme of exoplanet habitability.” says Schulze-Makuch (et al). “The first tier consists of an Earth Similarity Index (ESI), which allows worlds to be screened with regard to their similarity to Earth, the only known inhabited planet at this time.”

Right now, an international science team representing NASA, SETI,the German Aerospace Center, and four universities are ready to propose two major questions dealing with our quest for life – both as we assume and and alternate. According to the WSU news release:

“The first question is whether Earth-like conditions can be found on other worlds, since we know empirically that those conditions could harbor life,” Schulze-Makuch said. “The second question is whether conditions exist on exoplanets that suggest the possibility of other forms of life, whether known to us or not.”

Within the next couple of weeks, Schulze-Makuch and his nine co-authors will publish a paper in the Astrobiology journal outlining their future plans for exoplanet classification. The double approach will consist of an Earth Similarity Index (ESI), which will place these newly found worlds within our known parameters – and a Planetary Habitability Index (PHI), that will account for more extreme conditions which could support surrogate subsistence.

“The ESI is based on data available or potentially available for most exoplanets such as mass, radius, and temperature.” explains the team. “For the second tier of the classification scheme we propose a Planetary Habitability Index (PHI) based on the presence of a stable substrate, available energy, appropriate chemistry, and the potential for holding a liquid solvent. The PHI has been designed to minimize the biased search for life as we know it and to take into account life that might exist under more exotic conditions.”

Assuming that life could only exist on Earth-like planets is simply narrow-minded thinking, and the team’s proposal and modeling efforts will allow them to judiciously filter new discoveries with speed and high level of probability. It will allow science to take a broader look at what’s out there – without being confined to assumptions.

“Habitability in a wider sense is not necessarily restricted to water as a solvent or to a planet circling a star,” the paper’s authors write. “For example, the hydrocarbon lakes on Titan could host a different form of life. Analog studies in hydrocarbon environments on Earth, in fact, clearly indicate that these environments are habitable in principle. Orphan planets wandering free of any central star could likewise conceivably feature conditions suitable for some form of life.”

Of course, the team admits an alien diversity is surely a questionable endeavor – but why risk the chance of discovery simply on the basis that it might not happen? Why put a choke-hold on creative thinking?

“Our proposed PHI is informed by chemical and physical parameters that are conducive to life in general,” they write. “It relies on factors that, in principle, could be detected at the distance of exoplanets from Earth, given currently planned future (space) instrumentation.”

Original News Source: WSU News. For Further Reading: A Two-Tiered Approach to Assessing the Habitability of Exoplanets.

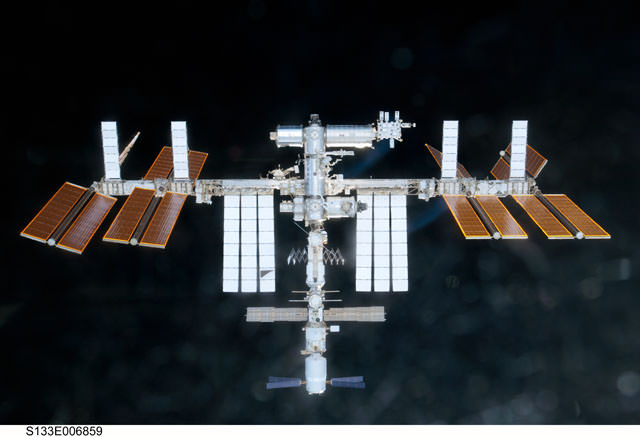

ISS Crew May Be Forced to Take Shelter from Space Debris

[/caption]

Nov. 23 update: NASA reports that flight controllers have downgraded conjunction threat, and there is now no need for the crew to shelter in place on the space station.

What a fine welcome for the new crew on board the ISS: The three astronauts/cosmonauts on the space station may have to take shelter in their Soyuz spacecraft early Wednesday morning (Nov. 23), due to a close flyby or even a possible collision with a piece of space debris. Mission Control called up to the Expedition 30 at 2:06 pm EST today (Nov. 22), saying it was too late to do a debris avoidance maneuver with the entire station, and the crew should be ready to “shelter in place” in the Soyuz vehicle.

Reports are that the object is a piece of debris about 4 inches (10 centimeters) in diameter from the Chinese Fengyun 1C weather satellite that was destroyed in 2007. Current tracking indicates the object may come within 850 meters (2,800 feet) of the station.

An approach of debris is considered close only when it enters an imaginary “pizza box” shaped region around the station, measuring 0.75 kilometers above and below the station and 25 kilometers on each side (2,460 feet above and below and 15.6 by 15.6 miles). The undocking of the Expedition 29 crew yesterday altered the orbit of the ISS enough so that this object –which had previously not been a threat – is now on its way for a very close pass with the station.

Commander Dan Burbank and Flight Engineers Anton Shkaplerov and Anatoly Ivanishin will awake early and confer with Mission Control on the latest tracking data of the object, and decide by 4:30 a.m. EST (0930 UTC) on Nov. 23 if they should take shelter in the Soyuz.

NASA’s Chief Scientist for Orbital Debris Nicholas Johnson told Universe Today during a previous close conjunction of space debris and the ISS that on average, close approaches to ISS occur about three times a month.

Johnson said that small pieces of debris have already collided with ISS on many occasions, but these debris to date have not affected the safety of the crew or the operation of the mission. “The dedicated debris shields on ISS can withstand particles as large as 1 cm in diameter,” he said.

The crew has taken shelter in the Soyuz vehicles only twice during the 11 years of continual human presence on the ISS.

Mars Rover Finds a Turkey Haven for the Holiday

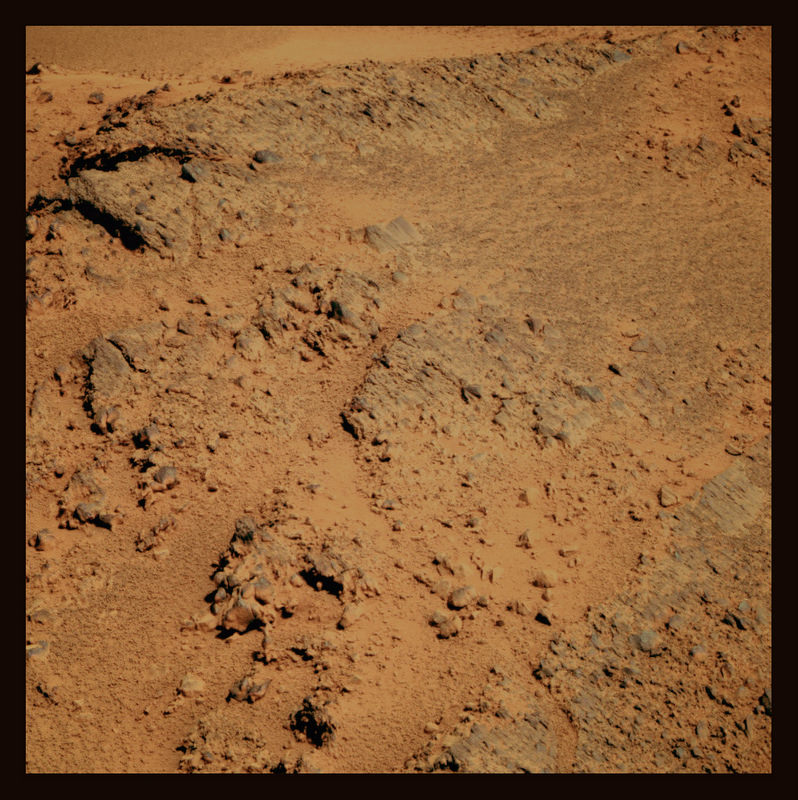

[/caption]

What does a Mars Rover do for the Thanksgiving holiday? While one rover will be sitting on the launchpad, preparing to head to the Red Planet (MSL/ Curiosity) the Opportunity rover has now trekked to an enticing outcrop near the summit of Cape York on the rim of Endeavour Crater. This summit or ridge has been named “Turkey Haven” by the MER science team, as this is where Oppy will conduct scientific studies over the four-day-long US holiday. The image above was taken a few days ago, showing the Turkey Haven ridge. Our pal Stu Atkinson has provided a beautiful color rendering, and you can see all the rocks that the rover will be looking at more closely with its suite of instruments and cameras. You can see more images of this area, including 3-D versions on Stu’s site, Road to Endeavour.

Oppy is now sitting among these rocks studying the outcrop region seen on the left.

And there’s other enticing regions ahead to study as well.

A dagger-shaped gorge or geological fault, as seen from above by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter may well be a future destination, but likely after Oppy finds another haven – a winter haven – a good place and location for soaking up as much sunshine as possible for the upcoming long winter on Mars.

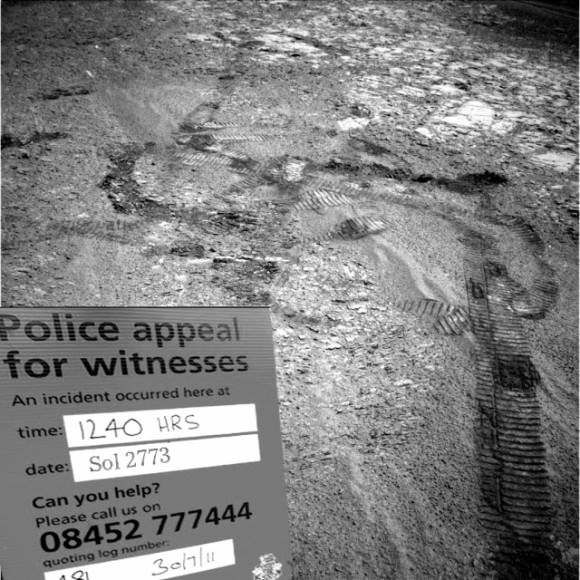

But behind Oppy was a most intriguing light-colored rock outcropping – this one was named “Homestake.” The rover spent several days studying the rock – even doing what could be termed a cruel drive-by (or driver-over). You can see in this image below, how Oppy really created havoc and a mess with her studies of this region:

…leading Stu Atkinson to create this:

But seriously, many Mars rover fans are anxiously waiting to hear from the science team about what they found during Oppy’s close-up studies of this unusual rock outcropping.

Opportunity’s odometer reading is now over 21.33 miles (34,328.09 meters, or 34.33 kilometers).

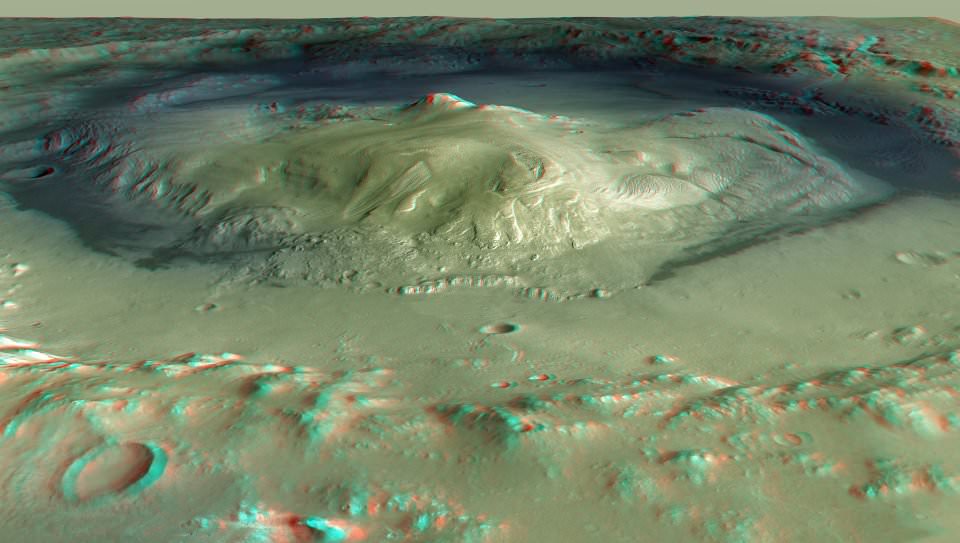

Science Rich Gale Crater and NASA’s Curiosity Mars Rover in Glorious 3-D – Touchdown in a Habitable Zone

[/caption]

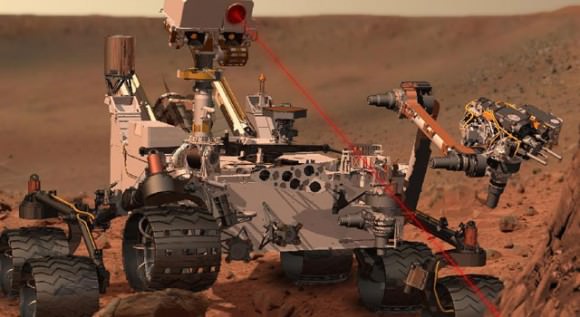

Curiosity, NASA’s next Mars rover is on target to launch this Saturday, Nov 26 from the Florida Space Coast in less than four days at 10:02 a.m. NASA is utilizing a first-of- its- kind pinpoint landing system for targeting Curiosity to touchdown inside Gale Crater – one of the most scientifically interesting locations on the Red Planet because it exhibits exposures of clay minerals that formed in the presence of neutral liquid water that could be conducive to the genesis of life.

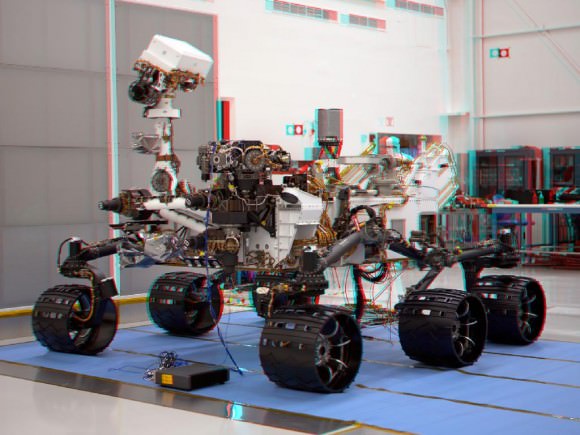

For a dramatic glimpse of the ragged and richly varied terrain of the 154 kilometer (96 mile) wide Gale Crater check out the glorious 3 D stereo image above. Another 3 D image, below, shows Curiosity being tested at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena. Calif., earlier this year.

“From NASA’s prior missions we’ve learned that Mars is a dynamic planet,” said Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA’s Mars exploration program, at a pre-launch briefing for reporters at the Kennedy Space Center.

“We’ve learned that it has a history where it was warm and wet at the same time that life started here on Earth. And we know it’s undergone a massive transition from that more benign time to what it is today.”

“Mars is worth exploring because of the potential for its having been habitable, at least in its past,” said Meyer.

Gale crater is dominated by a layered mountain rising some 5 km (3 mi) above the crater floor, readily apparent in the images above and below.

Color coding in this image of Gale Crater on Mars represents differences in elevation. The vertical difference from a low point inside the landing ellipse for NASA's Curiosity Mars Science Laboratory (yellow dot) to a high point on the mountain inside the crater (red dot) is about 3 miles (5 kilometers). Credit: NASA

“Liquid water was not short term in the past on ancient Mars. It has a role in carving out channels and depositing sediments in the past within craters that were carried by the water,” said Bethany Ehlmann of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif, at the briefing.

“Clays and carbonates are minerals that form in the presence of liquid water. The presence of clays in particular indicate the long-term presence of water interacting with the rocks and causing alteration of minerals. Clays also have water in their chemical structure as hydrates.”

NASA is targeting a landing ellipse – 20 by 25 kilometers (12.4 miles by 15.5 miles) – located in the northern portion of Gale and visible in the foreground.

The landing site was selected from some 60 candidates by the science team and NASA because it features an alluvial fan likely formed by water-carried sediments containing the clay minerals and is highlighted in another image below.

The lower layers of the nearby mountain — within driving distance for Curiosity — contain clay minerals and sulfates indicating a wet history on ancient Mars.

“Gale Crater is about as big as the Los Angeles basin,” said MSL project scientist John Grotzinger of JPL and Caltech, at the briefing. The mountain in the middle is as high as Mt Whitney, the tallest mountain in the lower 48 US states.”

“Over the course of the mission me might be about to go to the top of the nearby mound. At the base of the mound we see strata that are composed of clays.

“In one location, we can drive the rover through all these successive different environments and sample these different periods in Martian history,” explained Grotzinger.

All systems are “GO” at this time and the weather outlook currently looks favorable for an on time liftoff of Curiosity atop an Atlas V rocket from Space Launch Complex 41.

This stereoscopic anaglyph image was created from a left and right stereo pair of images of the Mars Science Laboratory mission's rover, Curiosity. The scene appears three dimensional when viewed through red-blue glasses with the red lens on the left. The image was taken May 26, 2011, in Spacecraft Assembly Facility at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. The mission is scheduled to launch during the period Nov. 26 to Dec. 18, 2011, and land the rover Curiosity on Mars in August 2012. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Complete Coverage of Curiosity – NASA’s Next Mars Rover launching 26 Nov. 2011

Read continuing features about Curiosity by Ken Kremer starting here:

Curiosity Powered Up for Martian Voyage on Nov. 26 – Exclusive Message from Chief Engineer Rob Manning

NASA’s Curiosity Set to Search for Signs of Martian Life

Curiosity Rover Bolted to Atlas Rocket – In Search of Martian Microbial Habitats

Closing the Clamshell on a Martian Curiosity

Curiosity Buttoned Up for Martian Voyage in Search of Life’s Ingredients

Assembling Curiosity’s Rocket to Mars

Encapsulating Curiosity for Martian Flight Test

Dramatic New NASA Animation Depicts Next Mars Rover in Action

Packing a Mars Rover for the Trip to Florida; Time Lapse Video

Test Roving NASA’s Curiosity on Earth