[/caption]

Over the past 21 years, the Hubble Space Telescope has gathered boatloads of data, with the Hubble archive center filling about 18 DVDs for every week of the telescope’s life. Now, with improved data mining techniques, an intense re-analysis of HST images from 1998 has revealed some hidden treasures: previously undetected extrasolar planets.

Scientists say this discovery helps prove a new method for planet hunting by using archived Hubble data. Also, discovering the additional exoplanets in the Hubble data helps them compare earlier orbital motion data to more recent observations.

How did astronomers detect the previously unseen exoplanets, and can the methods used be applied to other HST data sets?

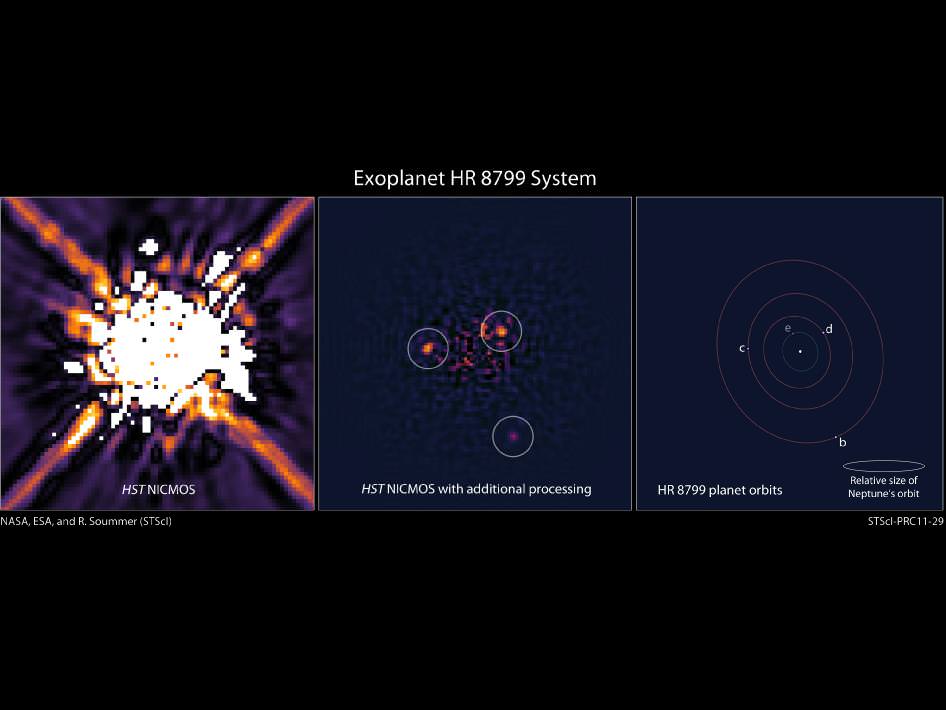

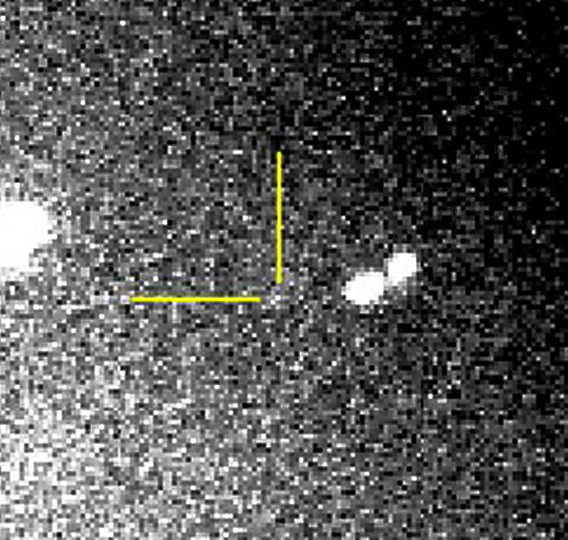

This isn’t the first time hidden exoplanets have been revealed in HST data – In 2009 David Lafreniere of the University of Montreal recovered hidden exoplanet data in Hubble images of HR 8799. The HST images Lafreniere studied were taken in 1998 with the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS). The outermost planet orbiting HR 8799 was identified and demonstrated the power of a new data-processing technique which could tease out faint planets from the glow of their central star.

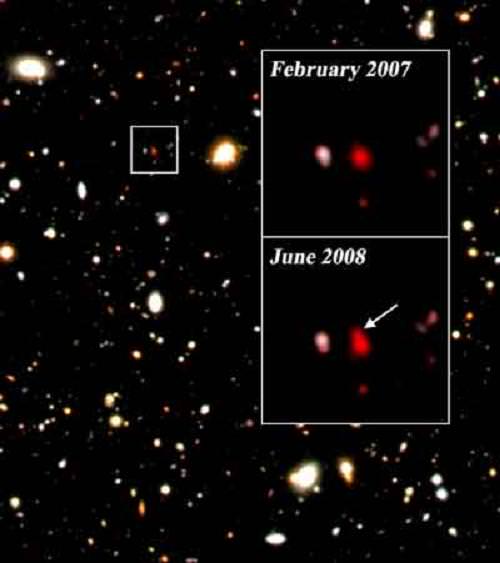

Four giant planets are now known to orbit HR 8799, the first three of which were discovered in 2007/2008 in near-infrared images taken with instruments at the W.M. Keck Observatory and the Gemini North telescope by Christian Marois of the National Research Council in Canada. In 2010 Marois and his team uncovered a fourth, innermost, planet. What makes the HR 8799 system so unique is that it is the only multi-exoplanet star system that has been directly imaged.

The new analysis by Remi Soummer of the Space Telescope Science Institute has found all three of the outer planets. Unfortunately, the fourth, innermost planet is close to HR 8799 and cannot be imaged due obscuration by the the NICMOS coronagraph that blocks the central star’s light.

When astronomers study exoplanets by directly imaging them, they study images taken several years apart – not unlike methods used to find Pluto and other dwarf planets in our solar system like Eris. Understanding the orbits in a multi-planet system is critical since massive planets can affect the orbits of their neighboring planets in the system. “From the Hubble images we can determine the shape of their orbits, which brings insight into the system stability, planet masses and eccentricities, and also the inclination of the system,” says Soummer.

Making the study difficult is the extremely long orbits of the three outer planets, which are approximately 100, 200, and 400 years, respectively. The long orbital periods require considerable time to produce enough motion for astronomers to study. In this case however, the added time span from the Hubble data helps considerably. “The archive got us 10 years of science right now,” Soummer says. “Without this data we would have had to wait another decade. It’s 10 years of science for free.”

Given its 400 year orbital period, in the past ten years, the outermost planet has barely changed position. “But if we go to the next inner planet we see a little bit of an orbit, and the third inner planet we actually see a lot of motion,” Soummer added.

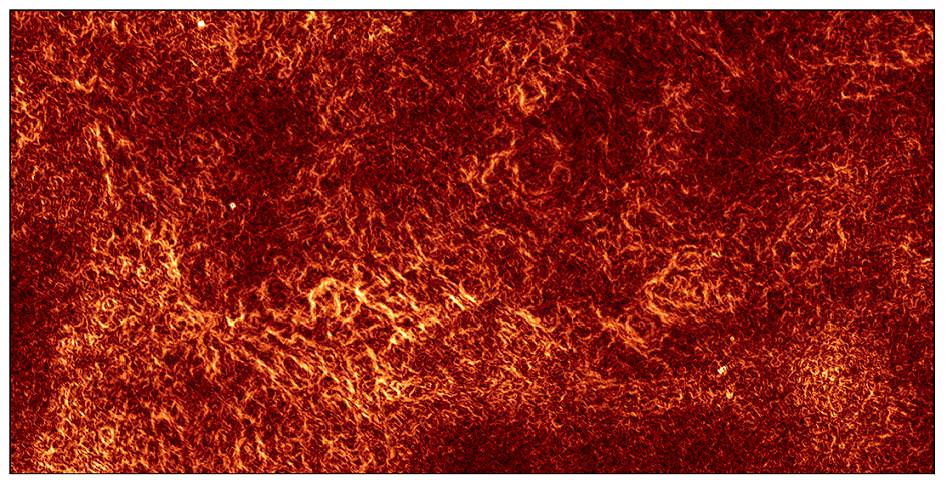

When the original HST data was analyzed, the methods used to detect exoplanets such as those orbiting HR 8799 were not available. Techniques to subtract the light from a host star still left residual light that drowned out the faint exoplanets. Soummer and his team improved on the previous methods and used over four hundred images from over 10 years of NICMOS observations.

The improvements on the previous technique included increasing contrast and minimizing residual starlight. Soummer and his team also successfully removed the diffraction spikes, a phenomenon that amateur and professional telescope imaging systems suffer from. With the improved techniques, Soummer and his team were able to see two of HR 8799’s faint inner planets, which are about 1/100,000th the brightness of the host star in infra-red.

Soummer has made plans to next analyze 400 more stars in the NICMOS archive with the same technique, which demonstrates the power of the Hubble Space Telescope data archive. How many more exoplanets are uncovered is anyone’s guess.

Finding these new exoplanets proves that even after the HST is no longer functioning, Hubble’s data will live on, and scientists will rely on Hubble’s revelations for years as they continue in their quest to understand the cosmos.

Source: Hubble Space Telescope Mission Updates