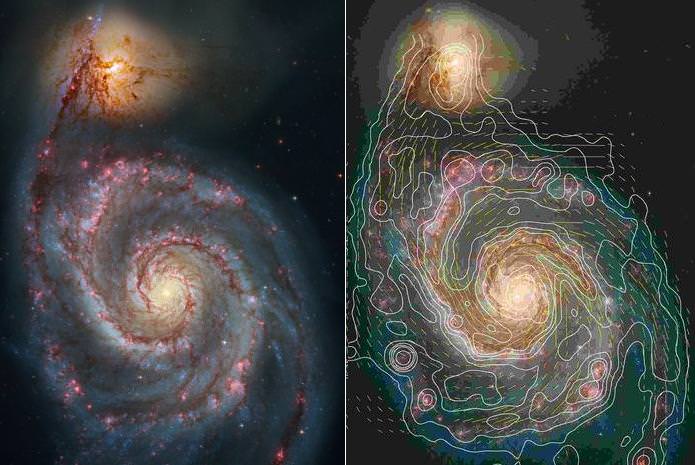

There’s a new concept in the works regarding the evolution of galactic arms and how they move across the structure of spiral galaxies. Robert Grand, a postgraduate student at University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory, used new computer modeling to suggest that these signature features of spiral galaxies – including our own Milky Way – evolve in different ways than previously thought.

The currently accepted theory is as spiral galaxies rotate, the “arms” are actually transient structures that move across the flattened disc of stars surrounding the galactic bulge, yet don’t directly affect the movement of the individual stars themselves. This would work in much the same way as a “wave” goes across a crowd at a stadium event. The wave moves, but the individual people do not move along with it – rather, they stay seated after it has passed.

However when Grand researched this suggested motion using computer models of galaxies, he and his colleagues found that this was not what tended to happen. Instead the stars actually moved along with the arms, rather than maintaining their positions.

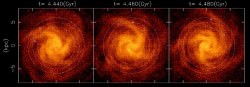

Also it was observed in these models that the arms themselves are not permanent features, but rather break up and reform over the course of 80 to 100 million years. Grand suggests that this may be due to the powerful gravitational shear forces generated by the spinning of the galaxy.

“We simulated the evolution of spiral arms for a galaxy with five million stars over a period of 6 billion years. We found that stars are able to migrate much more efficiently than anyone previously thought. The stars are trapped and move along the arm by their gravitational influence, but we think that eventually the arm breaks up due to the shear forces.”

– Robert Grand

The computer models also showed that the stars along the leading edge of the arms tended to move inwards toward the galactic center while the stars lining the trailing ends were carried to the outer edge of the galaxy.

Since it takes hundreds of millions of years for a spiral galaxy to complete even just one single rotation, observing their evolution and morphology is impossible to do in real time. Researchers like Grand and his simulations are key to our eventual understanding of how these islands of stars formed and continue to shape themselves into the vast, varied structures we see today.

“This research has many potential implications for future observational astronomy, like the European Space Agency’s next corner stone mission, Gaia, which MSSL is also heavily involved in. As well as helping us understand the evolution of our own galaxy, it may have applications for regions of star formation.”

– Robert Grand

The results were presented at the Royal Astronomical Society’s National Astronomy Meeting in Wales on April 20. Read the press release on the Royal Astronomical Society’s website here.

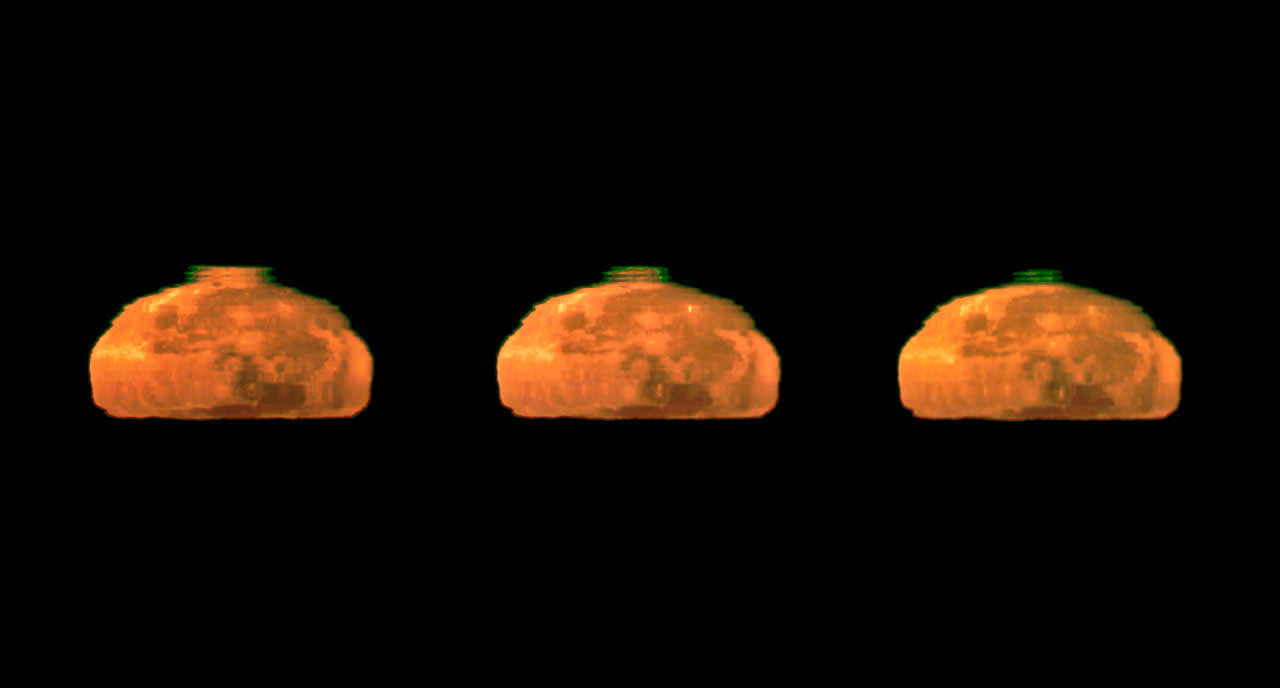

Top image: M81, a spiral galaxy similar to our own Milky Way, is one of the brightest galaxies that can be seen from Earth. The spiral arms wind all the way down into the nucleus and are made up of young, bluish, hot stars formed in the past few million years, while the central bulge contains older, redder stars. Credit: NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)