[/caption]

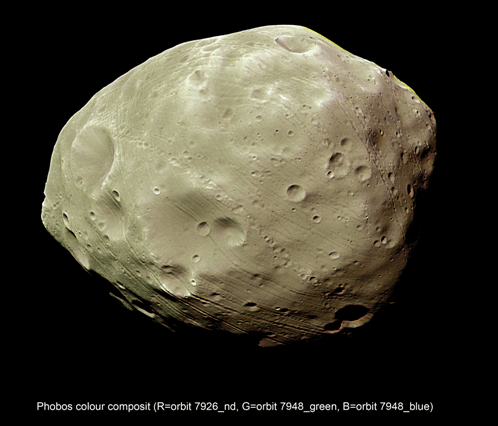

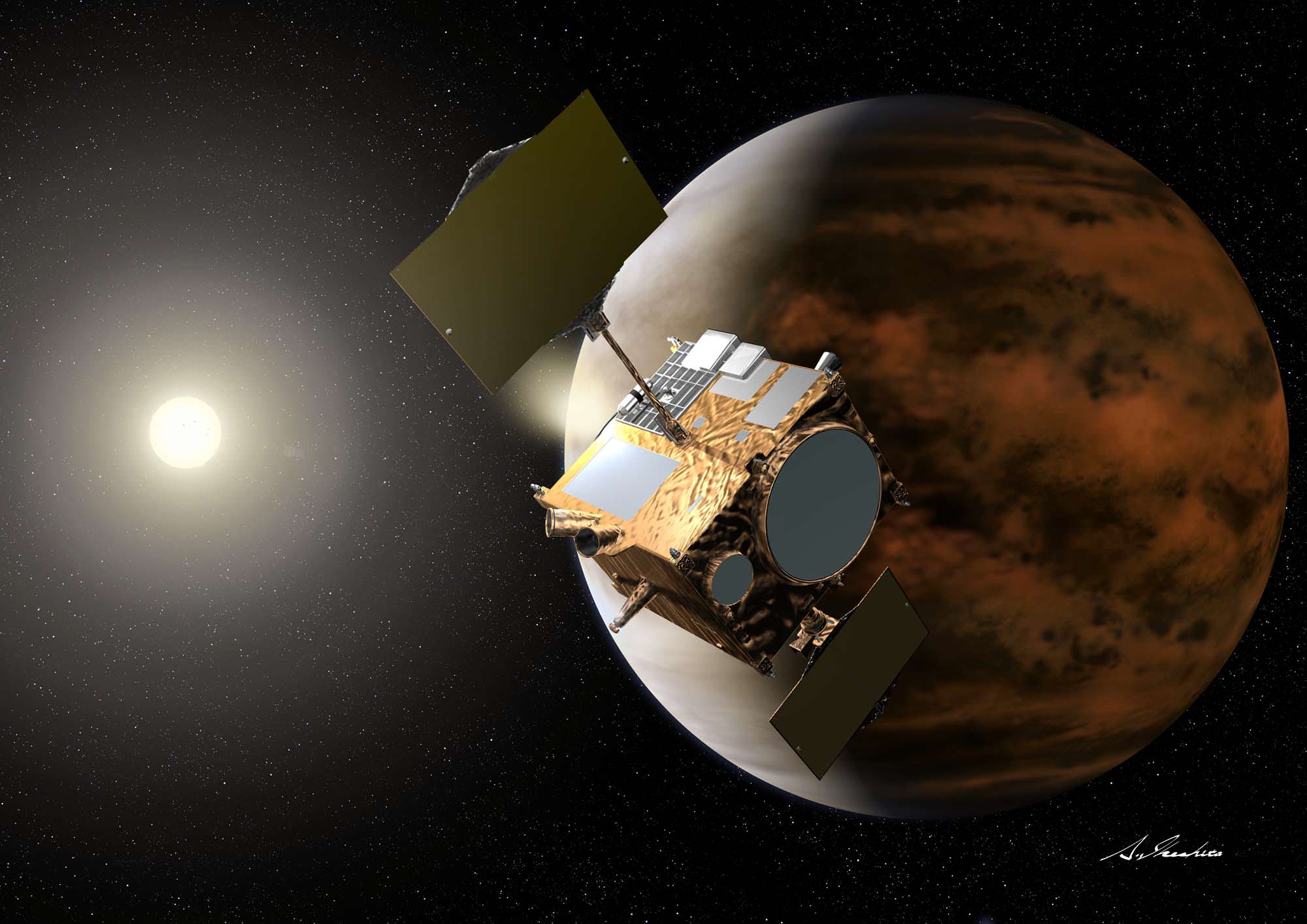

The Mars Express spacecraft will be making a very close flyby of the moon Phobos Sunday, January 9, 2011, at a distance of only 111 km from the center of the moon. The spacecraft actually is having eight different fairly close flybys of Phobos between December 20, 2010 and 16 January 2011, but this is the closest of that group. The Sunday buzz-by will be the third closest that Mars Express has performed during its time in orbit at Mars. The flyby speed will be about 3 km/s.

Olivier Witasse, ESA Project Scientist for Mars Express did a Q&A about the flyby with the Mars Express blog, which we’ll post below.

Q: What is the prime objective of this fly-by?

Witasse: The prime objective is to obtain high-resolution data from all remote sensing instruments, and especially to acquire what we hope will be spectacular images using the High Resoultion Stereo Camera (HRSC).

Q: What do the camera team hope to achieve?

Witasse: The HRSC camera will cover the southern hemisphere, which has not been well imaged during previous encounters. It should achieve a ground resolution of about a few metres per pixel. The emphasis will be on stereo imaging. These new data will improve the Phobos elevation model. This time, no colour data will be taken.

Q: Will any other instruments be working?

Witasse: The OMEGA, PFS and SPICAM experiments will acquire new data in the ultraviolet, visible and infrared ranges. This will significantly improve a data set used to map the surface temperatures. Also, and this is very important, the data are being used to find out the composition of Phobos. This is a very difficult exercise, because the spectra lack the obvious signatures of known components such as minerals.

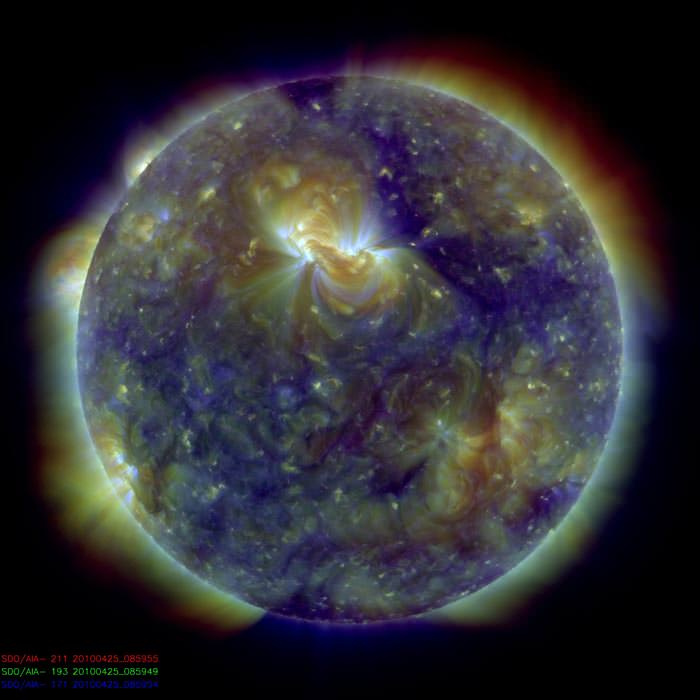

The MARSIS radar will also be working, attempting to obtain echoes from beneath the surface. To complete the picture, the ASPERA experiment will record signatures of the interaction between the solar wind and Phobos, by detecting solar wind particles bouncing off the surface.

All these new data can help unlock the origin of the Martian moons, and will certainly support the Russian sample return mission, Phobos-Grunt, expected to be launched later this year. Unfortunately, the Phobos-Grunt landing site will be at the fringes of view this time and so poorly illuminated.

Q: Why no radio science this time?

Witasse: Given the design of the Mars Express spacecraft, we always have to make a choice between radio-science and remote sensing. In other words, we cannot point the camera towards the target and the high-gain antenna towards Earth at the same time.

For this particular flyby, at 111 km, we decided to give priority to remote sensing for many reasons. Flybys over the illuminated side of Phobos obviously favour the operations of the imagers and spectrometers. Also, the altitude of this flyby is not ideal for radio-science. To improve the gravity data set, we would need to fly below 60 km. Furthermore, at the moment Mars is far from Earth and close to the Sun (as seen from Earth), making the quality of radio-signal unsuitable for a detailed scientific analysis.

——————

In another blog post, the Mars Express team said to expect no pictures from the flyby until January 21, because the whole Phobos data set won’t be downloaded to Earth until January 18. The HRSC team will then process the data, and we can expect a release of images (including a 3D view) on Friday, 21 January.

Source: Mars Express Blog