[/caption]

NASA recently celebrated the anniversary of the historic Apollo 12 lunar landing mission with another history making craft – the long lived Opportunity Mars rover. Opportunity traversed around and photographed ‘Intrepid’ crater on Mars in mid November 2010. The crater is informally named in honor of the ‘Intrepid’ lunar module which landed two humans on the surface of the moon on 19 November 1969, some forty one years ago.

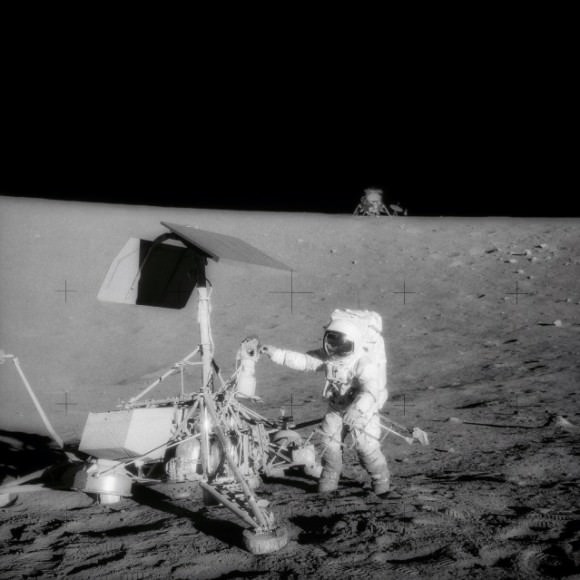

Apollo 12 was only the second of NASA’s Apollo missions to place humans on the Earth’s moon. Apollo astronauts Pete Conrad and Gordon Bean precisely piloted their lunar landing spacecraft nicknamed ‘Intrepid’ to a safe touchdown in the ‘Ocean of Storms’, a mere 180 meters (600 feet) away from the Surveyor 3 robotic lunar probe which had already landed on the moon in April 1967. The unmanned Surveyor landers paved the way for NASA’s manned Apollo landers.

As Conrad and Bean walked on the moon and collected lunar rocks for science, the third member of the Apollo 12 crew, astronaut Dick Gordon, orbited alone in the ‘Yankee Clipper’ command module and collected valuable science data from overhead.

On the anniversary of the lunar landing, the rover science team decided to honor the Apollo 12 mission as Opportunity was driving east and chanced upon a field of small impact craters located in between vast Martian dune fields. Informal crater names are assigned by the team to craters spotted by Opportunity in the Meridiani Planum region based on the names of historic ships of exploration.

Rover science team member James Rice, of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md., suggested using names from Apollo 12 because of the coincidental timing according to NASA. “The Apollo missions were so inspiring when I was young, I remember all the dates. When we were approaching these craters, I realized we were getting close to the Nov. 19 anniversary for Apollo 12,” Rice said. He sent Bean and Gordon photographs that Opportunity took of the two craters named for the two Apollo 12 spaceships.

Bean wrote back the following message to the Mars Exploration Rover team: “I just talked with Dick Gordon about the wonderful honor you have bestowed upon our Apollo 12 spacecraft. Forty-one years ago today, we were approaching the moon in Yankee Clipper with Intrepid in tow. We were excited to have the opportunity to perform some important exploration of a place in the universe other than planet Earth where humans had not gone before. We were anxious to give it our best effort. You and your team have that same opportunity. Give it your best effort.”

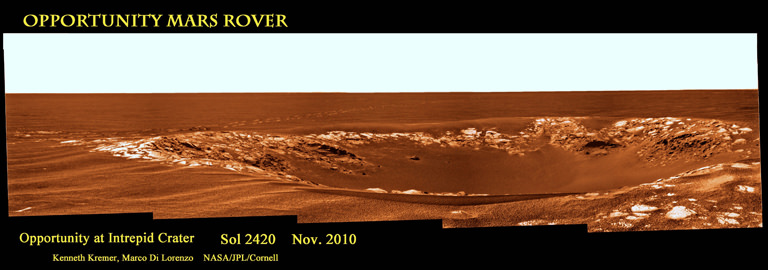

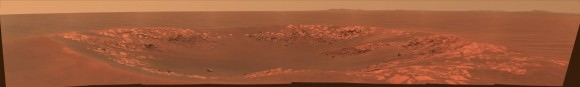

On November 4, Opportunity drove by and imaged ‘Yankee Clipper’ crater. After driving several more days she reached ‘Intrepid’ on November 9. The rover then traversed around the crater rim and photographed the crater interior from different vantage points, collecting two panoramic views along the way.

The rover team assembled the initial tribute panoramic mosaic taken on Sol 2417 (Nov. 11) and which can be seen here in high resolution along with ‘Yankee Clipper’.

Opportunity soon departed Intrepid on Sol 2420 (Nov. 14) to resume her multi-year trek eastwards and took a series of crater images that day – from a very different direction – which we were inspired to assemble into a panoramic mosaic (in false color) in tribute to the Apollo 12 mission (see above).

Our mosaic tribute clearly shows the rover wheel tracks as Opportunity first approached Intrepid on Nov. 9 – which is fittingly reminiscent of the Apollo 12 astronauts walking on the moon 41 years ago as they explored a lunar crater. By comparison, the arrival mosaic from Sol 2417 shows distant Endeavour crater in the background.

Intrepid crater is about 16 meters in diameter, thus similar in size to ‘Eagle’ crater inside which Opportunity first landed on 24 January 2004 after a 250 million mile ‘hole in one shot’ from Earth. Eagle was named in honor of the Apollo 11 mission.

“Intrepid is fairly eroded with sand filling the interior and ejecta blocks planed off by the saltating sand”, said Matt Golembek, Mars Exploration Program Landing Site Scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena, Calif. Asked about the age of Intrepid crater, Golembek told me; “Based on the erosional state it is at least several million years old, but less than around 20 million years old.”

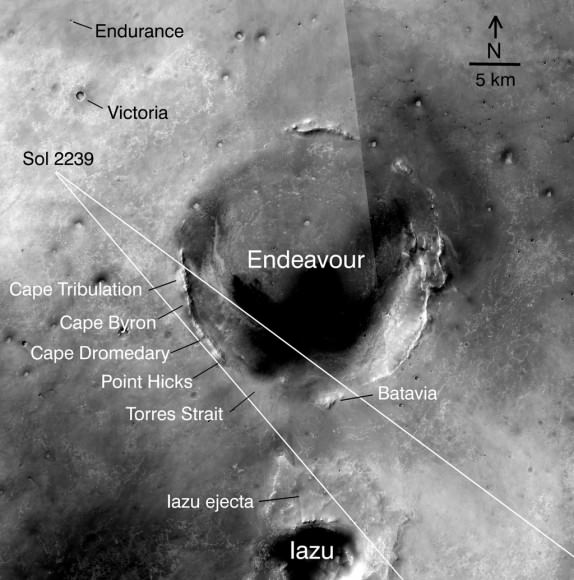

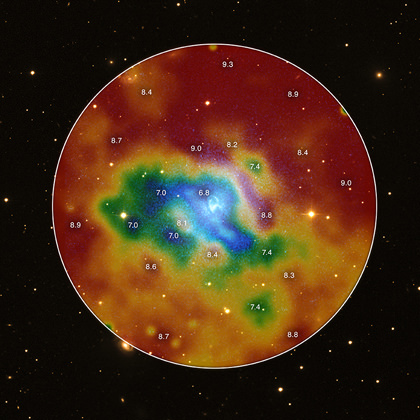

Opportunity is blazing ahead towards a huge 22 km (14 mile) wide crater named ‘Endeavour’, which shows distinct signatures of clays and past wet environments based on orbital imagery thus making the crater a compelling science target.

“Intrepid is 1.5 km from Santa Maria crater and about 7.5 km from Endeavour.”

“We should be at Santa Maria crater next week, where we will spend the holidays and conjunction. Then it will be 6 km to Endeavour,” Golembek said.

The road ahead looks to be alot friendlier to the intrepid rover. “The terrain Opportunity is on is among the smoothest and easiest to traverse since Eagle and Endurance. Should be smooth sailing to Endeavour, averaging about 100 meters per drive sol. We should easily beat MSL to the phyllosilicates,” Golembek explained.

Phyllosilicates are clay minerals that form under wet, warm, non-acidic conditions. They have never before been studied on the Martian surface.

MSL is the Mars Science Lab, NASA’s next Mars lander mission and which is scheduled to blast off towards the end of 2011. Golembek leads the landing site selection team.

The amazing Opportunity rover has spent nearly seven years roving the Martian surface, conducting a crater tour during her very unexpectedly long journey at ‘Meridiani Planum’ on Mars which now exceeds 26 km (16 miles). The rovers were designed with a prime mission “warranty” of just 90 Martian days – or sols – and have vastly exceeded their creators expectations.

“What a ride. This still does not seem real,” Rob Manning told me. Manning headed the Entry, Descent and Landing team at JPL for both the Spirit and Opportunity rovers. “That would be fantastic if Opportunity could get to the phyllosilicates before MSL launches.”

Stay tuned.