[/caption]

In 1937, an ordinary 16th magnitude star in the constellation Orion began to brighten steadily. Thinking it was a nova, astronomers were astounded when the star just kept getting brighter and brighter over the course of a year. Most novae burst forth suddenly and then begin to fade within weeks. But this star, now glowing at 9th magnitude, refused to fade. Adding to the puzzle, astronomers could see there was a gaseous nebula nearby shining from the reflected light of this mysterious star, now named FU Orionis. What was this new kind of star?

FU Ori has remained in this high state, around 10th magnitude ever since. Because this was a form of stellar variability never seen before and there were no other examples of this behavior, astronomers were forced to learn what they could from the only known example, or wait for another event to provide more clues.

Finally, more than 30 years later, FU Ori-like behavior appeared again in 1970 when the star now known as V1057 Cyg increased in brightness by 5.5 magnitudes over 390 days. Then in 1974, a 3rd example was discovered when V1515 Cyg rose from 17th magnitude to 12th magnitude over an interval lasting years. Astronomers began piecing the puzzle together from these clues.

FU Orionis stars, commonly called FUOrs, are pre-main sequence stars in the early stages of stellar development. They have only just formed from clouds of dust and gas in interstellar space, which occur in active star- forming regions. They are all associated with reflection nebulae, which become visible as the star brightens.

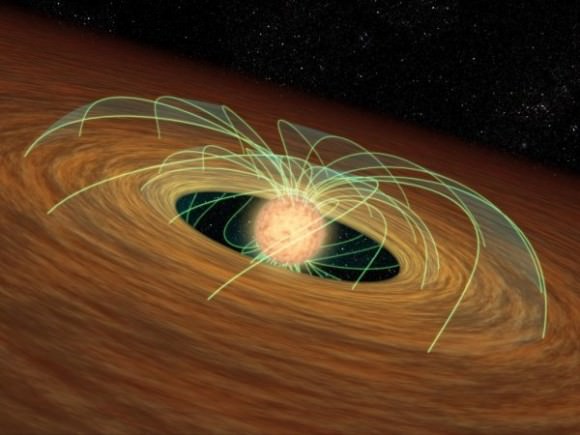

Astronomers are interested in these systems because FUOrs may provide us with clues to the early history of stars and the formation of planetary systems. At this early stage of evolution, a young stellar object (YSO) is surrounded by an accretion disk, and matter is falling onto the outer regions of the disk from the surrounding interstellar cloud. Thermal instabilities, most likely in the inner portions of the accretion disk, initiate an outburst and the young star increases its luminosity. Our Sun probably went through similar events as it was developing.

One of the major challenges in studying FU Orionis stars is the relatively small number of known examples. Although approximately 20 FU Orionis candidates have been identifed, only a handful of these stars have been observed to rise from their pre-outburst state to their eruptive state.

Now, in the last year, several new FUOrs have been discovered. In November 2009, two newly discovered objects were announced. Patrick Wils, John Greaves and the Catalina Real-time Transient Survey (CRTS) collaboration had discovered them in CRTS images.

The first of these objects appeared to coincide with the infrared source IRAS 06068-0641 in Monoceros. Discovered on Nov. 10, it had been continuously brightening from at least early 2005, when it was magnitude 14.8, to its present 12.6 magnitude. A faint cometary reflection nebula was visible to the east. A spectrum taken with the SMARTS 1.5-m telescope at Cerro Tololo, on Nov. 17, confirmed it to be a YSO. The object lies inside a dark nebula to the south of the Monocerotis R2 association, and is likely related to it.

Also inside this dark nebula, a second object, coincident with IRAS 06068-0643, had been varying between mag 15 and 20 over the past few years, much like UX-Ori-type objects with very deep fades. This second object is also associated with a variable cometary reflection nebula, extending to the north.

Light curves, spectra and images can be found here.

Then, in August 2010, two new eruptive, pre-main sequence stars were discovered in Cygnus. The first object was an outburst of the star HBC 722. The object was reported to have risen by 3.3 magnitudes from May 13 to August 16, 2010. Spectroscopy reported by Ulisse Munari on August 23rd, support this object’s classification as an FU Ori star. Munari and his team reported the object at 14.04V on Aug 21, 2010.

The second object, coincident with another infrared source, IRAS 20496+4354, was discovered by K. Itagaki of Yamagata, Japan, on August 23, 2010. The object appears very faint, approximately magnitude 20, in a Digital Sky Survey image taken in 1990. Subsequent spectroscopy and photometry of this object by Munari showed that this object also has the characteristics of an FU Ori star. Munari reported the object at 14.91V on August 26, 2010.

Both these objects are now the subjects of an AAVSO observing campaign announced October 1, 2010 in AAVSO Alert Notice 425. Dr. Colin Aspin, University of Hawai’i, has requested the help of AAVSO observers in performing long-term photometric monitoring of these two new YSOs in Cygnus. AAVSO observations will be used to help calibrate optical and near-infrared spectroscopy to be obtained during the next year.

Since these stars are newly discovered, very little is known about their behavior. Their classification as FU Ori variables is based on spectroscopy, but establishing a good optical light curve and maintaining it, over the next several years, will be crucial to understanding these stars. This kind of long-term monitoring is one of the things at which amateur astronomers excel.

So after a very slow start, discoveries of new YSOs and our understanding of the dusty disk environments around them are starting to heat up. With new tools and new examples to study we are peering into the early stages of stellar and planetary formation and finding some of our models have been pretty close to the truth. We expect to find more and similar objects as new all-sky surveys begin to cover the sky, but these objects will still be relatively rare and therefore interesting, because this period in a star’s evolution is short-lived and only takes place in the active star forming regions of galaxies.