In some respects, the field of astronomy has been a rapidly changing one. New advances in technology have allowed for exploration of new spectral regimes, new methods of image acquisition, new methods of simulation, and more. But in other respects, we’re still doing the same thing we were 100 years ago. We take images, look to see how they’ve changed. We break light into its different colors, looking for emission and absorption. The fact that we can do it faster and to further distances has revolutionized our understanding, but not the basal methodology.

But recently, the field has begun to change. The days of the lone astronomer at the eyepiece are already gone. Data is being taken faster than it can be processed, stored in easily accessible ways, and massive international teams of astronomers work together. At the recent International Astronomers Meeting in Rio de Janeiro, astronomer Ray Norris of Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) discussed these changes, how far they can go, what we might learn, and what we might lose.

Observatories

One of the ways astronomers have long changed the field is by collecting more light, allowing them to peer deeper into space. This has required telescopes with greater light gathering power and subsequently, larger diameters. These larger telescopes also offer the benefit of improved resolution so the benefits are clear. As such, telescopes in the planning stages have names indicative of immense sizes. The ESO’s “Over Whelmingly Large Telescope” (OWL), the “Extremely Large Array” (ELA), and “Square Kilometer Array” (SKA) are all massive telescopes costing billions of dollars and involving resources from numerous nations.

But as sizes soar, so too does the cost. Already, observatories are straining budgets, especially in the wake of a global recession. Norris states, “To build even bigger telescopes in twenty years time will cost a significant fraction of a nation’s wealth, and it is unlikely that any nation, or group of nations, will set a sufficiently high priority on astronomy to fund such an instrument. So astronomy may be reaching the maximum size of telescope that can reasonably be built.”

Thus, instead of the fixation on light gathering power and resolution, Norris suggests that astronomers will need to explore new areas of potential discovery. Historically, major discoveries have been made in this manner. The discovery of Gamma-Ray Bursts occurred when our observational regime was expanded into the high energy range. However, the spectral range is pretty well covered currently, but other domains still have a large potential for exploration. For instance, as CCDs were developed, the exposure time for images were shortened and new classes of variable stars were discovered. Even shorter duration exposures have created the field of asteroseismology. With advances in detector technology, this lower boundary could be pushed even further. On the other end, the stockpiling of images over long times can allow astronomers to explore the history of single objects in greater detail than ever before.

Data Access

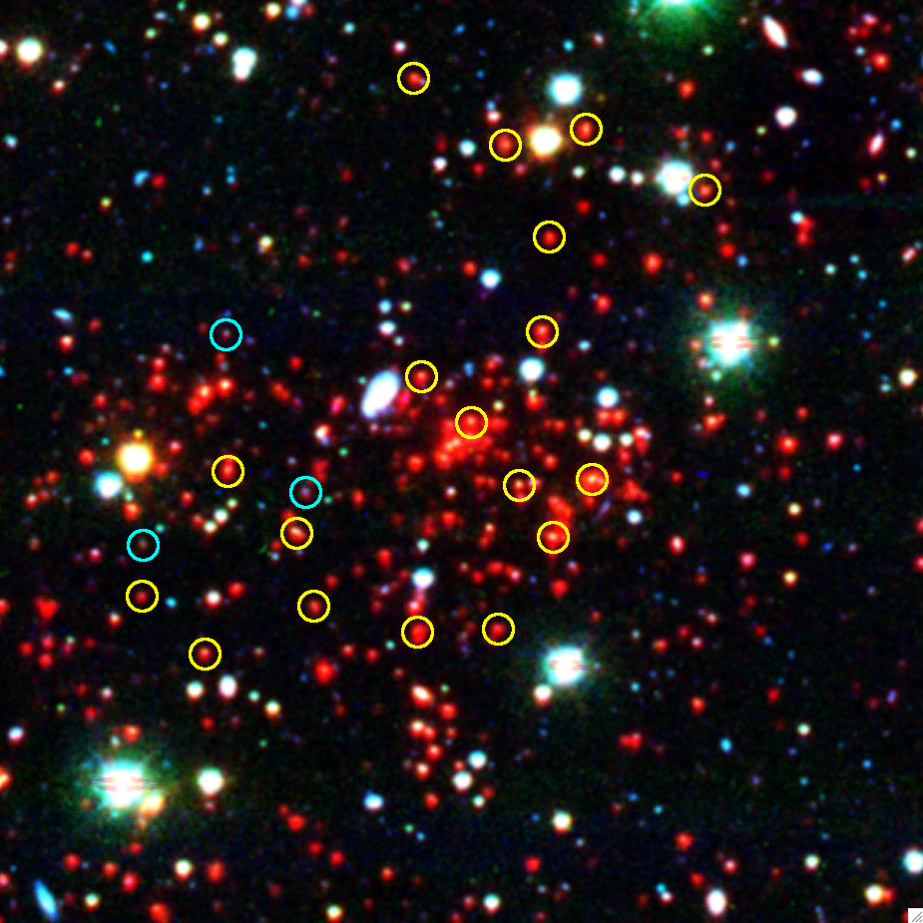

In recent years, many of these changes have been pushed forward by large survey programs like the 2 Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS) and the All Sky Automated Survey (ASAS) (just to name two of the numerous large scale surveys). With these large stores of pre-collected data, astronomers are able to access astronomical data in a new way. Instead of proposing telescope time and then hoping their project is approved, astronomers are having increased and unfettered access to data. Norris proposes that, should this trend continue, the next generation of astronomers may do vast amounts of work without even directly visiting an observatory or planning an observing run. Instead, data will be culled from sources like the Virtual Observatory.

Of course, there will still be a need for deeper and more specialized data. In this respect, physical observatories will still see use. Already, much of the data taken from even targeted observing runs is making it into the astronomical public domain. While the teams that design projects still get first pass on data, many observatories release the data for free use after an allotted time. In many cases, this has led to another team picking up the data and discovering something the original team had missed. As Norris puts it, “much astronomical discovery occurs after the data are released to other groups, who are able to add value to the data by combining it with data, models, or ideas which may not have been accessible to the instrument designers.”

As such, Nelson recommends encouraging astronomers to contribute data to this way. Often a research career is built on numbers of publications. However, this runs the risk of punishing those that spend large amounts of time on a single project which only produces a small amount of publication. Instead, Nelson suggests a system by which astronomers would also earn recognition by the amount of data they’ve helped release into the community as this also increases the collective knowledge.

Data Processing

Since there is a clear trend towards automated data taking, it is quite natural that much of the initial data processing can be as well. Before images are suitable for astronomical research, the images must be cleaned for noise and calibrated. Many techniques require further processing that is often tedious. I myself have experienced this as much of a ten week summer internship I attended, involved the repetitive task of fitting profiles to the point-spread function of stars for dozens of images, and then manually rejecting stars that were flawed in some way (such as being too near the edge of the frame and partially chopped off).

While this is often a valuable experience that teaches budding astronomers the reasoning behind processes, it can certainly be expedited by automated routines. Indeed, many techniques astronomers use for these tasks are ones they learned early in their careers and may well be out of date. As such, automated processing routines could be programmed to employ the current best practices to allow for the best possible data.

But this method is not without its own perils. In such an instance, new discoveries may be passed up. Significantly unusual results may be interpreted by an algorithm as a flaw in the instrumentation or a gamma ray strike and rejected instead of identified as a novel event that warrants further consideration. Additionally, image processing techniques can still contain artifacts from the techniques themselves. Should astronomers not be at least somewhat familiar with the techniques and their pitfalls, they may interpret artificial results as a discovery.

Data Mining

With the vast increase in data being generated, astronomers will need new tools to explore it. Already, there has been efforts to tag data with appropriate identifiers with programs like Galaxy Zoo. Once such data is processed and sorted, astronomers will quickly be able to compare objects of interest at their computers whereas previously observing runs would be planned. As Norris explains, “The expertise that now goes into planning an observation will instead be devoted to planning a foray into the databases.” During my undergraduate coursework (ending 2008, so still recent), astronomy majors were only required to take a single course in computer programming. If Norris’ predictions are correct, the courses students like me took in observational techniques (which still contained some work involving film photography), will likely be replaced with more programming as well as database administration.

Once organized, astronomers will be able to quickly compare populations of objects on scales never before seen. Additionally, by easily accessing observations from multiple wavelength regimes they will be able to get a more comprehensive understanding of objects. Currently, astronomers tend to concentrate in one or two ranges of spectra. But with access to so much more data, this will force astronomers to diversify further or work collaboratively.

Conclusions

With all the potential for advancement, Norris concludes that we may be entering a new Golden Age of astronomy. Discoveries will come faster than ever since data is so readily available. He speculates that PhD candidates will be doing cutting edge research shortly after beginning their programs. I question why advanced undergraduates and informed laymen wouldn’t as well.

Yet for all the possibilities, the easy access to data will attract the crackpots too. Already, incompetent frauds swarm journals looking for quotes to mine. How much worse will it be when they can point to the source material and their bizarre analysis to justify their nonsense? To combat this, astronomers (as all scientists) will need to improve their public outreach programs and prepare the public for the discoveries to come.