This is a great: amateur rocketeers Luke Geissbuhler and his son Max launched their own DIY satellite via a weather balloon from New York, and using an HD video camera captured some amazing video of the contraption’s rise to near the edge of space (closer than a lot of us will ever get, anyway….) and its plummeting fall. You gotta love their enthusiasm and their “flight tests” at the beginning of the video. It might help that the Dad is a photographer that works in Hollywood films, but then again, I think Max’s countdown and lollipop were the real impetus behind the successful mission. They were able to track the device with GPS, and recover the camera. Lucky for us!

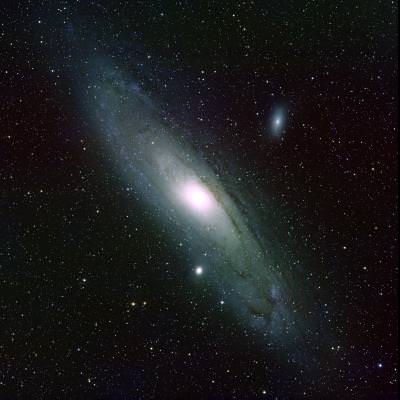

M31’s Odd Rotation Curve

Early on in astronomical history, galactic rotation curves were expected to be simple; they should operate much like the solar system in which inner objects orbit faster and outer objects slower. To the surprise of many astronomers, when rotation curves were eventually worked out, they appeared mostly flat. The conclusion was that the mass we see was only a small fraction of the total mass and that a mysterious Dark Matter must be holding the galaxies together, forcing them to rotate more like a solid body.

Recent observations of the Andromeda Galaxy’s (M31) rotation curve has shown that there may yet be more to learn. In the outermost edges of the galaxy, the rotation rate has been shown to increase. And M31 isn’t alone. According to Noordermeer et al. (2007) “in some cases, such as UGC 2953, UGC 3993 or UGC 11670 there are indications that the rotation curves start to rise again at the outer edges of the HI discs.” A new paper by a team of Spanish astronomers attempts to explain this oddity.

Although many spiral galaxies have been discovered with the odd rising rotational velocities near their outer edges, Andromeda is both one of the most prominent and the closest. Detailed studies from Corbelli et al. (2010) and Chemin et al. (2009), mapped out the rise in HI gas, showing that the velocity increases some 50 km/s in the outer 7 kiloparsecs mapped. This makes up a significant fraction of the total radius given the studies extended to only ~38 kiloparsecs. While conventional models with Dark Matter are able to reproduce the rotational velocities of the inner portions of the galaxy, they have not explained this outer feature and instead predict that it should slowly fall off.

The new study, led by B. Ruiz-Granados and J.A. Rubino-Martin from the Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias, attempts to explain this oddity using a force with which astronomers are very familiar: Magnetic fields. This force has been shown to decrease less rapidly than others over galactic distances and in particular, studies of M31’s magnetic field shows that it slowly changes angle with distance from the center of the galaxy. This slowly changing angle works in such a manner as to decrease the angle between the field and the direction of motion of particles within it. As a result, “the field becomes more tightly wound with increasing galactocentric distance” making the decrease in strength even slower.

Although galactic magnetic fields are weak by most standards, the sheer amount of matter they can affect and the charged nature of many gas clouds means that even weak fields may play an important role. M31’s magnetic field has been estimated to be ~4.6 microGauss. When a magnetic field with this value is added into the modeling equations, the team found that it greatly improved the fit of models to the observed rotation curve, matching the increase in rotational velocity.

The team notes that this finding is still speculative as the understanding of the magnetic fields at such distances is based solely on modeling. Although the magnetic field has been explored for the inner portions of the galaxy (roughly the inner 15 kiloparsecs), no direct measurement has yet been made in the regions in question. However, this model makes strict observational predictions which could be confirmed by future missions LOFAR and SKA.

Where In The Universe Challenge #121

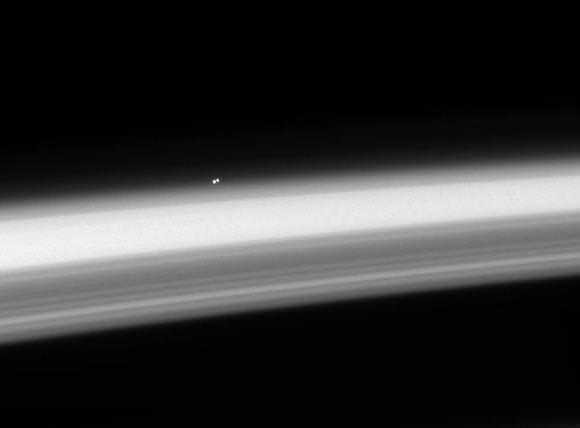

It’s time once again for another Where In The Universe Challenge. This awesome image was sent in by UT reader Paul Nadolny. Name where in the Universe this image was taken and give yourself extra points if you can name exactly what all the different objects are in the image, as well as what instrument is responsible. Post your guesses in the comments section, and check back on later at this same post to find the answer. To make this challenge fun for everyone, please don’t include links or extensive explanations with your answer. Good luck!

UPDATE: The answer has now been posted below.

You all are pretty sharp! Paul and I both thought looked like a star hovering over Earth’s limb. But actually, this is Saturn’s limb, with the nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, hanging above the horizon. Both Alpha Centauri A and B—stars very similar to our own—are clearly distinguishable in this image, which was taken by the Cassini spacecraft.

This image is part of a stellar occultation sequence, during which Cassini watches as a star (or stars) as it passes behind Saturn. Light from the stars is attenuated by the uppermost reaches of Saturn’s gaseous envelope, revealing information about the structure and composition of the planet’s atmosphere.

The view was captured from about 66 degrees above the ringplane and faces southward on Saturn. Ring shadows mask the planet’s northern latitudes at bottom.

Thanks again to Paul Nadolny for submitting this image. If you have an image you’d like to submit to try and stump everyone, send an email to Nancy.

Astronomy Cast Ep. 201: Titan

Titan is Saturn’s largest moon, and the second largest moon in the Solar System. It’s unique in the Solar System as the only moon with an atmosphere. In fact, scientists think that Titan’s thick atmosphere – rich in hydrocarbons – is similar to the early Earth, and could give us clues about how life got started on our planet.

Click here to download the episode

Titan – Show notes and transcript

Or subscribe to: astronomycast.com/podcast.xml with your podcatching software.

Viewing Alert: Bad Universe Episode 2

He’s back!!! Our pal Phil Plait the Bad Astronomer is back again on the Discovery Channel with the second episode of his new series, “Bad Universe.” It is on TONIGHT (October 6), so check your local listings here, and you can also find when it will be replayed in case you miss it. Above is a teaser/trailer of the second episode where Phil flies in an F-16 — it’s awesome! Just how much punishment can Phil’s frail, pale, scientist body take? Find out!

Can’t get enough? More videos are available on the Discovery Channel’s main Bad Universe video list. And by the way, Bad Universe will be shown immediately following Mythbusters this evening.

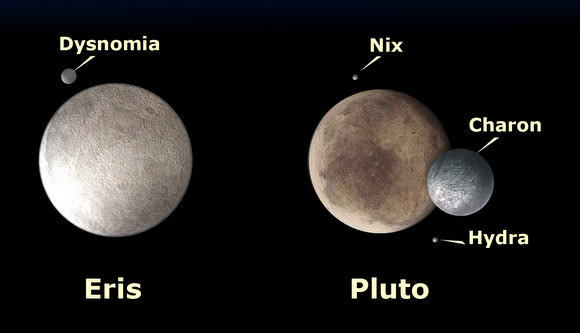

Eris and Pluto: Two Peas in a Pod

[/caption]

Or two dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt…

Eris — that pesky big dwarf planet that caused all the brouhaha about planets, dwarf planets, plutoids and the like — has gotten a closer look by a team of astronomers from several different universities, and guess what? Eris and Pluto have a lot in common. Eris appears to have a frozen surface, predominantly covered in nitrogen ice and methane, just like Pluto.

The scientists integrated two years of work conducted in Northern Arizona University’s new ice research laboratory, in addition to astronomical observations of Eris from the Multiple Mirror Telescope Observatory from Mount Hopkins, Ariz., and of Pluto from Steward Observatory from Kitt Peak, Ariz.

“There are only a handful of such labs doing this kind of work in the world,” said Stephen Tegler, from NAU and lead author of “Methane and Nitrogen Abundances on Eris and Pluto,” which was presented this week at the American Astronomical Society’s Divison of Planetary Science meeting. “By studying surfaces of icy dwarf planets, we hope to get a better understanding of the processes that affect their surfaces.”

NAU’s ice lab grew optically clear ice samples of methane, nitrogen, argon, methane-nitrogen mixtures, and methane-argon mixtures in a vacuum chamber at temperatures as low as minus 390 degrees Fahrenheit to simulate the planets’ cold surfaces. Light passed through the samples revealed the “chemical fingerprints” of molecules and atoms, which were compared to telescopic observations of sunlight reflected from the surfaces of Eris and Pluto.

“By combining the astronomical data and laboratory data, we found about 90 percent of Eris’s icy surface is made up of nitrogen ice and about 10 percent is made up of methane ice, which is not all that different from Pluto,” said David Cornelison, coauthor and physicist at Missouri State University.

The scientists say the recent findings will directly enhance NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft mission, currently scheduled to fly by Pluto in 2015, by lending greater value to the continued research of Eris and Pluto.

Source: Northern Arizona University, DPS

New VISTA Within the Unicorn

[/caption]

What a gorgeous new infrared image of the region within the Monoceros (Unicorn) constellation taken from ESO’s Paranal Observatory in northern Chile with the amazing VISTA: the Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy. This telescope has a huge field of view, a large mirror and a very sensitive camera and has been churning out image after fantastic image. In this one, VISTA is able to penetrates the dark curtain of cosmic dust and reveals in astonishing detail the folds, loops and filaments sculpted from the dusty interstellar matter by intense particle winds and the radiation emitted by hot young stars.

“When I first saw this image I just said ‘Wow!’” said Jim Emerson, of Queen Mary, University of London and leader of the VISTA consortium. “I was amazed to see all the dust streamers so clearly around the Monoceros R2 cluster, as well as the jets from highly embedded young stellar objects. There is such a great wealth of exciting detail revealed in these VISTA images.”

It shows an active stellar nursery hidden inside a massive dark cloud rich in molecules and dust. Although the Unicorn appears close in the sky to the more familiar Orion Nebula it is actually almost twice as far from Earth, at a distance of about 2,700 light-years.

The width of VISTA’s field of view is equivalent to about 80 light-years at this distance. Since the dust is largely transparent at infrared wavelengths, many young stars that cannot be seen in visible-light images become apparent. The most massive of these stars are less than ten million years old.

In visible light a grouping of massive hot stars creates a beautiful collection of reflection nebulae where the bluish starlight is scattered from parts of the dark, foggy outer layers of the molecular cloud. However, most of the new-born massive stars remain hidden as the thick interstellar dust strongly absorbs their ultraviolet and visible light.

This new image was created from exposures taken in three different parts of the near-infrared spectrum. In molecular clouds like Monoceros R2, the low temperatures and relatively high densities allow molecules to form, such as hydrogen, which under certain conditions emit strongly in the near infrared. Many of the pink and red structures that appear in the VISTA image are probably the glows from molecular hydrogen in outflows from young stars.

Read more about this image at the ESO website.

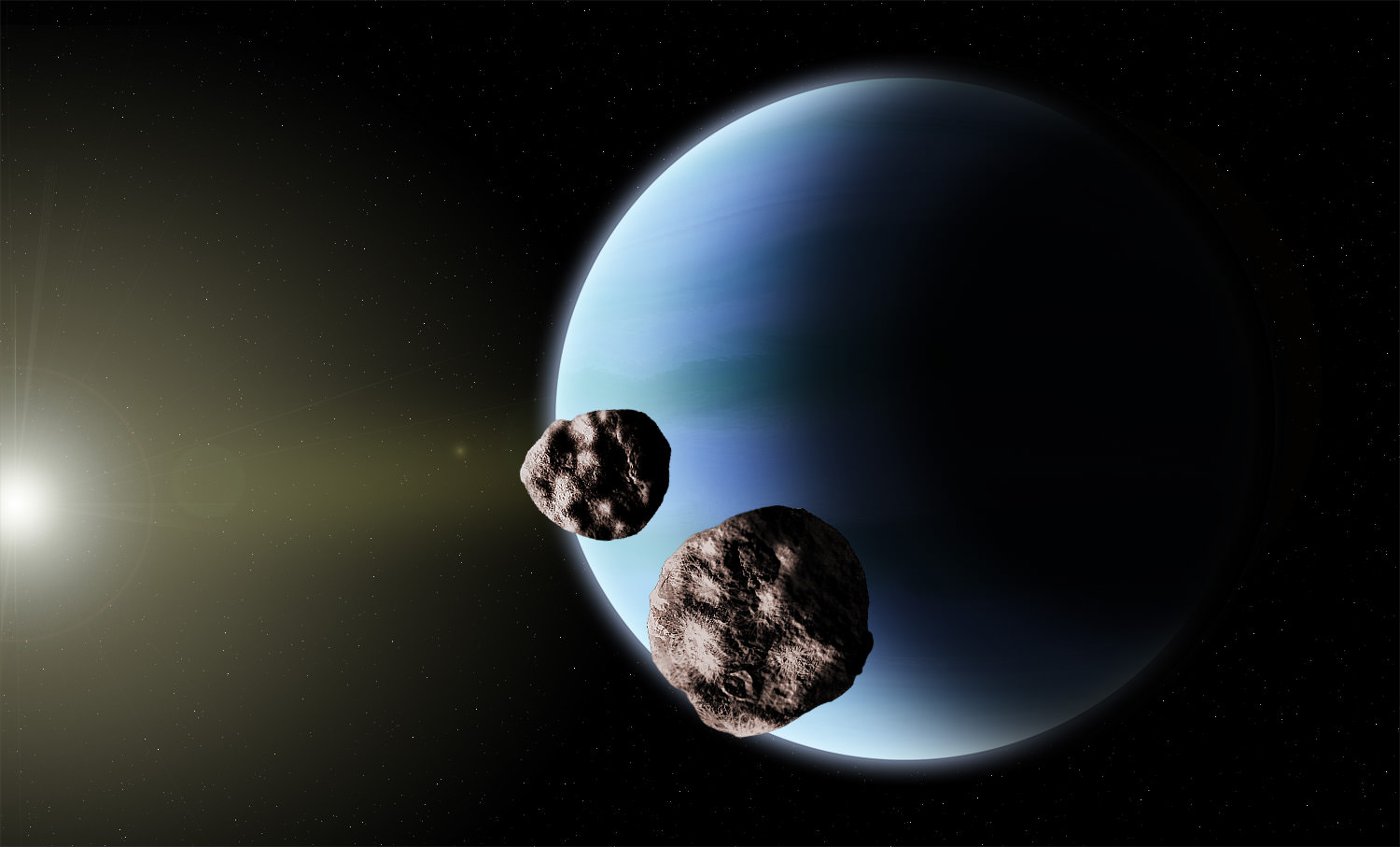

Neptune Acquitted on One Count of Harassment

[/caption]

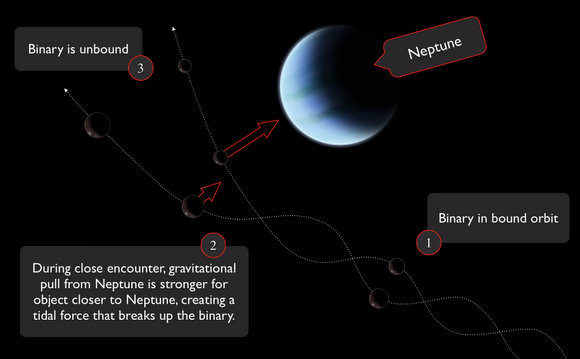

A very popular explanation for the dynamical evolution of our solar system is being challenged by a new model that takes the blame away from Neptune for knocking a collection of planetoids known as the Cold Classical Kuiper Belt out to their current, distant home. PhD student Alex Parker from the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada presented evidence showing that the large population of binary objects in the Kuiper Belt gives witness to a different series of events than the Nice Model – which says Neptune’s migrations were responsible for a sending KBO’s into chaotic orbits. “Kuiper binaries paint a different picture,” Parker said during a press briefing at the American Astronomical Society’s Division of Planetary Sciences meeting this week. “I should title my talk as ‘Neptune not guilty of harassment’ or perhaps more accurately, “Planet Neptune acquitted of one count of harassment.’”

The Nice Model holds that the objects in the scattered Kuiper Belt were placed in their current positions by interactions with Neptune’s migrating resonances. Originally, the Model says, the Kuiper belt was much denser and closer to the Sun, with an outer edge at approximately 30 AU. Its inner edge would have been just beyond the orbits of Uranus and Neptune, which were in turn far closer to the Sun when they formed. As Neptune migrated outward, it approached the objects in the proto-Kuiper belt, capturing some of them into resonances and sending others into chaotic orbits.

But the survey of the Kuiper Belt being done by Parker and his thesis supervisor Dr. J. J Kavelaars (Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics), which has been running for a decade, tells a different story. “Thirty per cent of Kuiper Belt Objects are binaries, some in very wide orbits around each other in a slow waltz, weakly bound to their partners,” Parker said. “These binaries should have been destroyed if the Kuiper Belt Objects were thrown out of solar system.”

Since binaries are extremely common in the Kuiper Belt, they are useful tools for astronomers, said Parker. “Pluto and Charon are the most famous of these binaries and since their orbits can be affected by their environment, we can use them to test what the interplanetary environment is like and what it was like in the past.”

Using computer simulations, the researchers determined that many binary systems in part of the Belt would have been destroyed by the manhandling they would have experienced if Neptune did indeed move the Kuiper Belt to its current location.

The survey characterizes the orbits of these binaries and found that many are extremely wide – the widest one is about 100,000 km – and they are very delicate. “Because they are so weakly bound they can be upset by collisions from small objects peppering the KBOs,” said Parker, “and they would not be there today if the members of this part of the Kuiper Belt were ever hassled by Neptune in the past.”

Additionally, the current environment of the Kuiper Belt does not lend itself to the creation of these binaries, so they have been interacting with each other for a very long time. The research done by Parker and his colleagues suggest that the Kuiper Belt formed near its present location and has remained undisturbed over the age of the solar system.

The new model also solves the missing mass problem for the Kuiper Belt, Parker said. “The Nice Model – as well as all the other models of the formation of the Kuiper Belt — suggests its density was much higher so the binaries could be generated, but we don’t see that density today.”

The Cold Classical Kuiper Belt lies in a very flat ring between 6 and 7 billion kilometers from the Sun, and contains thousands of bodies larger than 100 kilometers across. The Kuiper Belt is of special interest to astrophysicists because it is a fossil remnant of the primordial debris that formed the planets, said Parker. “Understanding the structure and history of the Kuiper Belt helps us better understand how the planets in our solar system formed, and how planets around other stars may be forming today.”

Read the team’s paper: “Destruction of Binary Minor Planets During Neptune Scattering,” Alex H. Parker, JJ Kavelaars

Sources: DPS meeting press briefing, DPS abstract, University of Victoria press release.

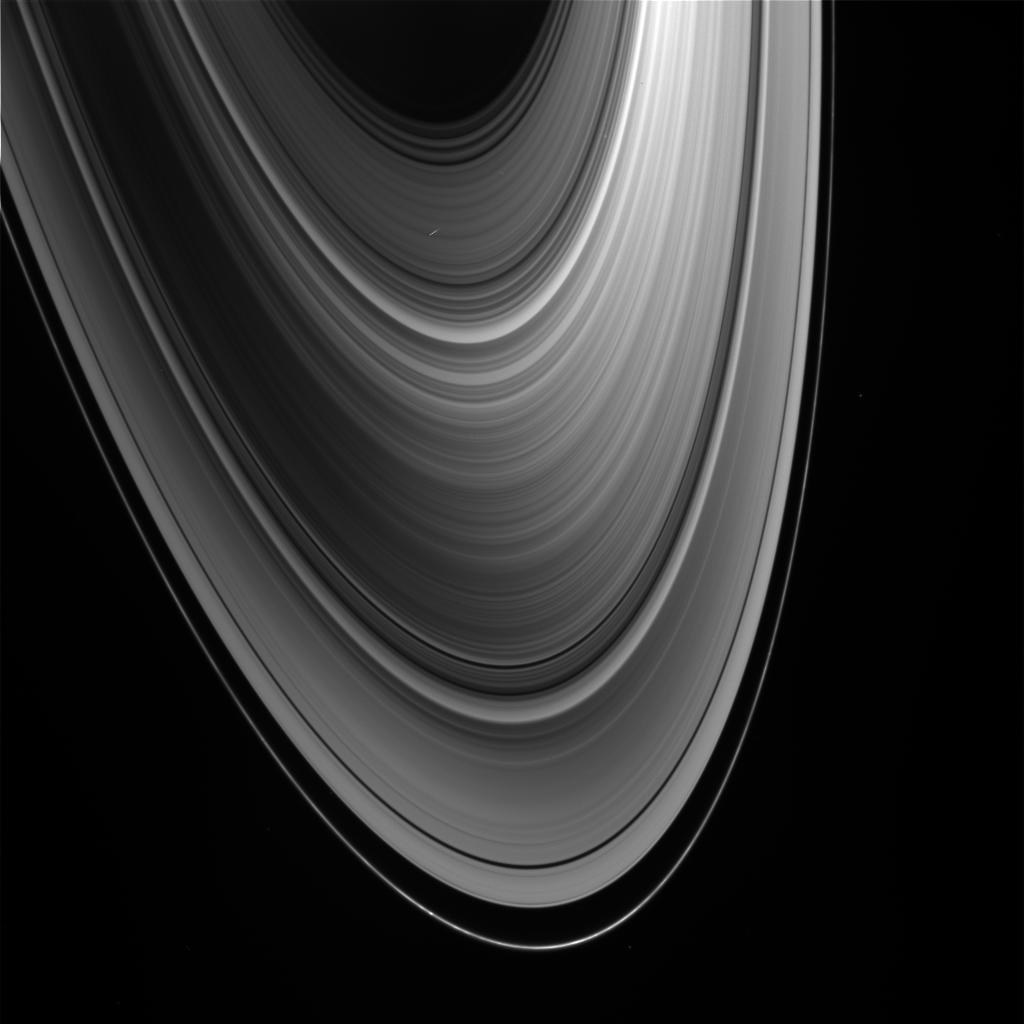

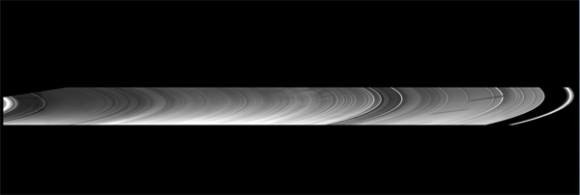

Saturn’s Rings Formed from Large Moon’s Destruction

[/caption]

The formation of Saturn’s rings has been one of the classical if not eternal questions in astronomy. But one researcher has provided a provocative new theory to answer that question. Robin Canup from the Southwest Research Institute has uncovered evidence that the rings came from a large, Titan-sized moon that was destroyed as it spiraled into a young Saturn.

Over the years, different theories have evolved on how the rings formed around Saturn. The two leading theories involve a small moon that was shattered by meteor impacts, or the tidal disruption of a comet coming too close to Saturn.

But Saturn’s main rings are about 90% water ice by mass, and because bombardment of the rings by micrometeoroids increases their rock content over time, Canup said the rings’ current composition implies that they were essentially pure ice when they formed.

However, disruption of a small moon would generally lead to a mixed rock-ice ring, while tidal disruptions of comets would occur much more often at Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune than at Saturn.

Additionally, neither of these theories would explain Saturn’s inner moons, which have low enough densities that they too must be comprised of nearly pure ice.

Canup’s new alternative theory is that Titan-sized moon with a rocky core and an icy mantle spiraled into Saturn early in solar system history. Tidal forces ripped off part of the icy mantle, distributing it into what would become the rings. But the rocky core was made of more durable material that held together until it hit Saturn’s surface. “The end result is a pure ice ring,” Canup said in an article in Nature.

Over time the ring spreads out and its mass decreases, and icy moons are created. Due to changes in the evolving Saturn system, these “spawned” moons then spiraled outward rather than inward. In this way, ice rings and ice-enhanced inner moons originate as a primordial byproduct of the same process that produces Saturn’s regular satellite system, making the whole process simpler than if there were several events.

Canup studies formation events with detailed computer simulations, including studying how our own Moon formed.

She presented her findings at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Science meeting this week, in Pasadena, California, and her presentation was detailed in an article in Nature.

Sources: Canup’s abstract, Nature

Trojans May Yet Rain Down

It would be an interesting survey to catalog the initial reactions readers have to “Trojans”. Do you think first of wooden horses, or do asteroids spring to mind? Given the context of this website, I’d hope it’s the latter. If so, you’re thinking along the right lines. But how much do you really know about astronomical Trojans?

While most frequently used to discuss the set of objects in Jupiter’s orbital path that lie 60º ahead and behind the planet, orbiting the L4 and L5 Lagrange points, the term can be expanded to include any family of objects orbiting these points of relative stability around any other object. While Jupiter’s Trojan family is known to include over 3,000 objects, other solar system objects have been discovered with families of their own. Even one of Saturn’s moons, Tethys, has objects in its Lagrange points (although in this case, the objects are full moons in their own right: Calypso and Telesto).

In the past decade Neptunian Trojans have been discovered. By the end of this summer, six have been confirmed. Yet despite this small sample, these objects have some unexpected properties and may outnumber the number of asteroids in the main belt by an order of magnitude. However, they aren’t permanent and a paper published in the July issue of the International Journal of Astrobiology suggests that these reservoirs may produce many of the short period comets we see and “contribute a significant fraction of the impact hazard to the Earth.”

The origin of short period comets is an unusual one. While the sources of near Earth asteroids and long period comets have been well established, short period comets parent locations have been harder to pin down. Many have orbits with aphelions in the outer solar system, well past Neptune. This led to the independent prediction of a source of bodies in the far reaches by Edgeworth (1943) and Kuiper (1951). Yet others have aphelions well within the solar system. While some of this could be attributed to loss of energy from close passes to planets, it did not sufficiently account for the full number and astronomers began searching for other sources.

In 2006, J. Horner and N. Evans demonstrated the potential for objects from the outer solar system to be captured by the Jovian planets. In that paper, Horner and Evans considered the longevity of the stability of such captures for Jupiter Trojans. The two found that these objects were stable for billions of years but could eventually leak out. This would provide a storing of potential comets to help account for some of the oddities.

However, the Jupiter population is dynamically “cold” and does not contain a large distribution of velocities that would lead to more rapid shedding. Similarly, Saturn’s Trojan family was not found to be excited and was estimated to have a half life of ~2.5 billion years. One of the oddities of the Neptunian Trojans is that those few discovered thus far have tended to have high inclinations. This indicates that this family may be more dynamically excited, or “hotter” than that of other families, leading to a faster rate of shedding. Even with this realization, the full picture may not yet be clear given that searches for Trojans concentrate on the ecliptic and would likely miss additional members at higher inclinations, thus biasing surveys towards lower inclinations.

To assess the dangers of this excited population, Horner teamed with Patryk Lykawka to simulate the Neptunian Trojan system. From it, they estimated the family had a half life of ~550 million years. Objects leaving this population would then undergo several possible fates. In many cases, they resembled the Centaur class of objects with low eccentricities and with perihelion near Jupiter and aphelion near Neptune. Others picked up energy from other gas giants and were ejected from the solar system, and yet others became short period comets with aphelions near Jupiter.

Given the ability for this the Neptunian Trojans to eject members frequently, the two examined how many of the of short period comets we see may be from these reservoirs. Given the unknown nature of how large these stores are, the authors estimated that they could contribute as little as 3%. But if the populations are as large as some estimates have indicated, they would be sufficient to supply the entire collection of short period comets. Undoubtedly, the truth lies somewhere in between, but should it lie towards the upper end, the Neptunian Trojans could supply us with a new comet every 100 years on average.