[/caption]

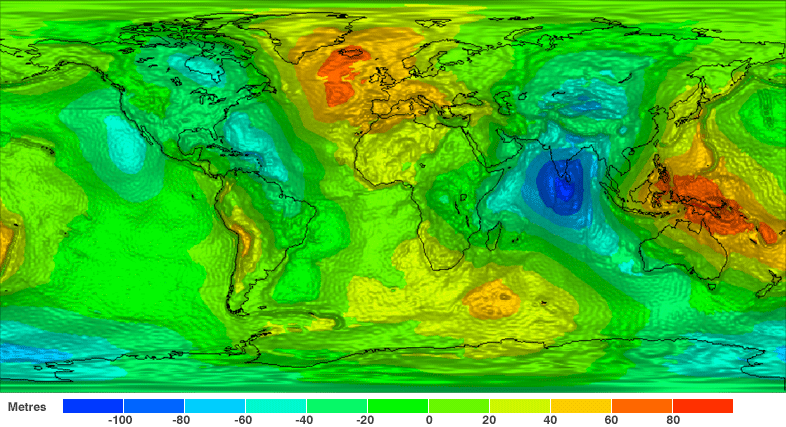

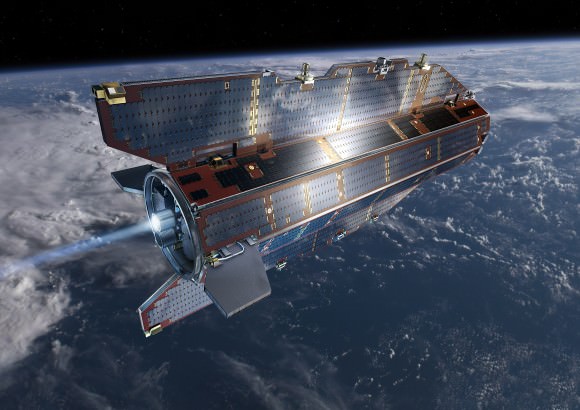

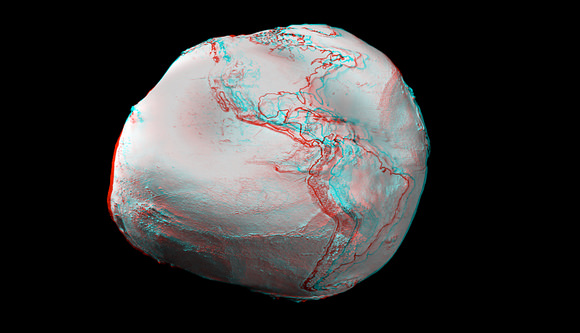

The sleek and sexy-looking GOCE satellite has provided a new, finely detailed look at Earth’s gravity – in high definition. This is the first-ever global gravity model and is based on just two months of data from the low-flying GOCE. “GOCE is delivering where it promised: in the fine spatial scales,” GOCE Mission Manager Rune Floberghagen said. “We have already been able to identify significant improvements in the high-resolution ‘geoid’, and the gravity model will improve as more data become available.”

GOCE stands for Gravity field and steady-state Ocean Circulation Explorer.

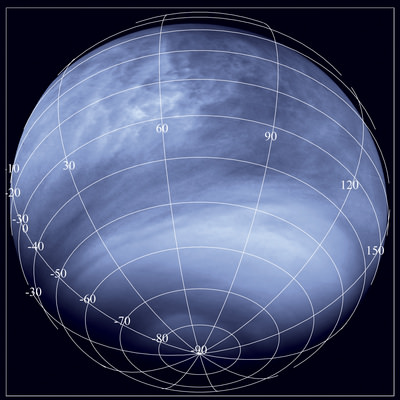

The geoid is a measure of the lumps and bumps in Earth’s gravity, and shows how the surface would look if an ocean covered the earth, also known as surface of equal gravitational attraction and mean sea level.

Scientists say it is a crucial reference for accurately measuring ocean circulation, sea-level change and ice dynamics – all affected by climate change.

The GOCE team presented their initial data at ESA’s Living Planet Symposium. ESA launched GOCE in March 2009, and the data is from November and December 2009.

“Over continents, and in particular in regions poorly mapped with terrestrial or airborne techniques, we can already conclude that GOCE is changing our understanding of the gravity field,” said Floberghagen. Over major parts of the oceans, the situation is even clearer, as the marine gravity field at high spatial resolution is for the first time independently determined by an instrument of such quality.”

This will greatly improve our knowledge and understanding of the Earth’s internal structure, and will be used as a much-improved reference for ocean and climate studies, including sea-level changes, oceanic circulation and ice caps dynamics survey. Numerous applications are expected in climatology, oceanography and geophysics.

“The computed global gravity field looks very promising. We can already see that important new information will be obtained for large areas of South America, Africa, Himalaya, South-East Asia and Antarctica,” said Prof. Reiner Rummel from Technische Universität München, Chairman of the GOCE Mission Advisory Group. “With each two-month cycle of data, the gravity model will become more detailed and accurate. I am convinced that the data will be of great interest to various disciplines of Earth sciences.”

The spacecraft can measure accelerations as small as 1 part in 10,000,000,000,000 of the gravity experienced on Earth.

GOCE flies in orbit at just 254.9 km (158 miles) mean altitude – the lowest orbit sustained over a long period by any Earth observation satellite, but the lower the altitude, the better the data.

The residual air at this low altitude causes the orbit of a standard satellite to decay very rapidly. So, to counteract the drag, the satellite fires an ion thruster using xenon gas, maintaining its orbit. This ensures the gravity sensors are flying as though they are in pure freefall, so they pick up only gravity readings and not the disturbing effects from other forces.

To obtain clean gravity readings, there can be no disturbances from moving parts, so the entire satellite is a single extremely sensitive measuring device.

The new map is just from the first data, and more information will be forthcoming. In May, ESA made available the first set of gravity gradients and ‘high-low satellite-to-satellite tracking’ to scientific and non-commercial users – and much more will come in the following months.