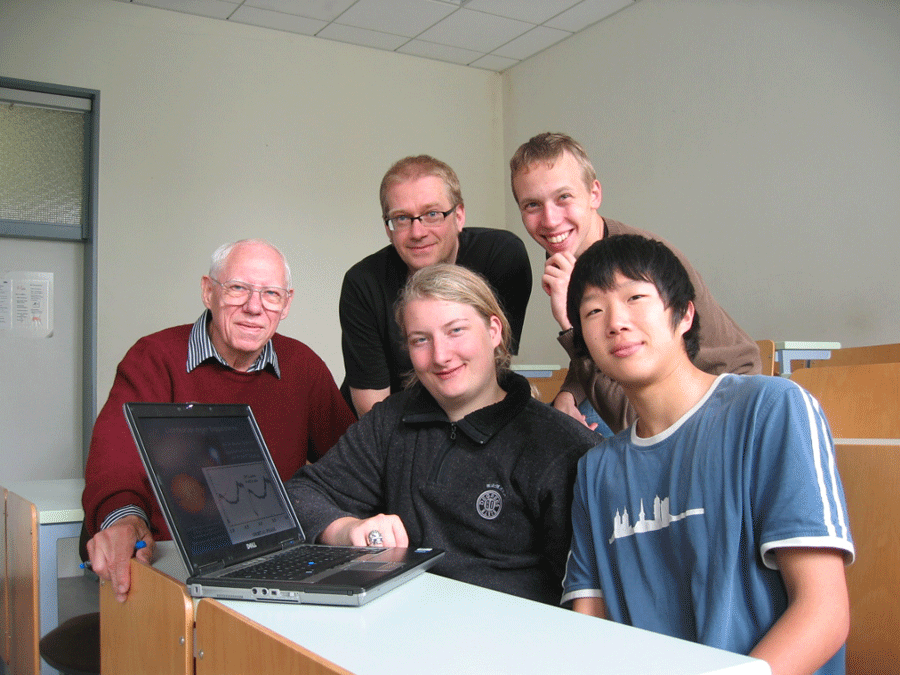

From the left: Klaus Beuermann (group leader), Jens Diese (back,teacher), and the high-school students Joshua Zachmann (front), Alexander-Maria Ploch (back), Sang Paik (front). JD, JZ, and AMP are from the Max-Planck-Gymnasium, SP is from the Felix-Klein-Gymnasium.

High school students from Germany have now done what many scientists strive for: had their research work published by a science journal. The Astronomy & Astrophysics science journal published a paper co-authored by three students who observed the light variations of the faint (19th magnitude) cataclysmic variable EK Ursae Majoris (EK UMa) over two months. Led by astronomer Klaus Beuermann from the University of Göttingen, and the students’ high school physics teacher, the team made use of a remotely-controlled 1.2-meter telescope in Texas. Astronomy & Astrophysics says the team “presents an accurate, long-term ephemeris,” and that “they participated in all the steps of a real research program, from initial observations to the publication process, and the result they obtained bears scientific significance.”

The students, Joshua Zachmann, Alexander-Maria Ploch, Sang Paik and their teacher, Jens Diese, made observations, analyzed the CCD images, produced and interpreted light curves, and looked at archival satellite data. Beuermann, the astronomer they worked with said, “Although it is fun to perform one’s own remote observations with a professional telescope from the comfort of a normal school classroom, it is even more satisfying to be involved in a project that provides new and publishable results rather than to perform experiments with predictable outcomes.”

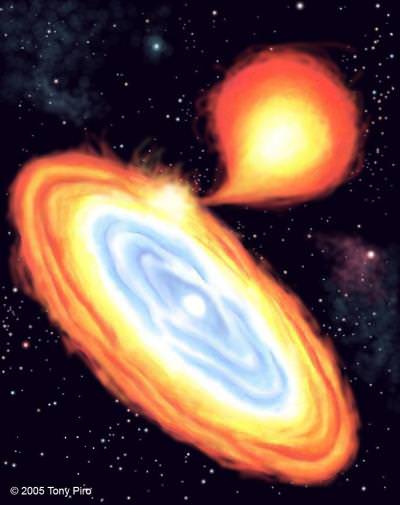

Cataclysmic variable research is a field where the contributions of small telescopes has a long tradition. Cataclysmic variables are extremely close binary systems containing a low-mass star whose material is being stripped off by the gravitational pull of a white dwarf companion. Due to the transfer of matter between the stars, these systems vary dramatically in brightness on timescales in the whole range between seconds and years. This largely unpredictable variability makes them ideal targets for school projects, particularly since professional observatories are generally unable to provide enough observation time for regular monitoring.

An accurate ephemeris is needed to keep track of the orbital motions of the two stars, but none was available because EK UMa is faint in the optical range and requires a long-term observation of the light variations. The strong magnetic field of the white dwarf turns the light of the hot matter striking the surface of the white dwarf into two “lighthouse” beams. By measuring the times of the minimum between the beams, the group was able to determine an orbital period accurate enough to keep track of the eclipse that took place in 1985, over 100 000 cycles earlier. By combining their own measurements with those made by the Einstein, ROSAT, and EUVE satellites, they estimated the orbital period over 137 000 cycles to an accuracy of a tenth of a millisecond. Surprisingly, the orbital period is extremely stable, although the period of such very close binaries is expected to vary due to the presence of third bodies and magnetic activity cycles on the companion star.

The team’s paper: (not yet available) A long-term optical and X-ray ephemeris of the polar EK Ursae Majoris, by K. Beuermann, J. Diese, S. Paik, A. Ploch, J. Zachmann, A.D. Schwope, and F.V. Hessman.

Source: Astronomy & Astrophysics