”]

Three different spacecraft have confirmed there is water on the Moon. It hasn’t been found in deep dark craters or hidden underground. Data indicate that water exists diffusely across the moon as hydroxyl or water molecules — or both — adhering to the surface in low concentrations. Additionally, there may be a water cycle in which the molecules are broken down and reformulated over a two week cycle, which is the length of a lunar day. This does not constitute ice sheets or frozen lakes: the amounts of water in a given location on the Moon aren’t much more than what is found in a desert here on Earth. But there’s more water on the Moon than originally thought.

The Moon was believed to extremely dry since the return of lunar samples from the Apollo and Luna programs. Many Apollo samples contain some trace water or minor hydrous minerals, but these have typically been attributed to terrestrial contamination since most of the boxes used to bring the Moon rocks to Earth leaked. This led the scientists to assume that the trace amounts of water they found came from Earth air that had entered the containers. The assumption remained that, outside of possible ice at the moon’s poles, there was no water on the moon.

Forty years later, an instrument on board the ill-fated Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft, the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M cubed) found that infrared light was being absorbed near the lunar poles at wavelengths consistent with hydroxyl- and water-bearing materials.

M3 analyzes the way that light from the sun reflects off the lunar surface to understand what materials comprise the lunar soil. Light is reflected in different wavelengths off of different minerals, and specifically, the instrument detected wavelengths of reflected light that would indicate a chemical bond between hydrogen and oxygen. Given water’s well-known chemical symbol, H2O, which represents two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom, this discovery was a source of great interest to the researchers.

The instrument can only see the very uppermost layers of the lunar soil – perhaps to a few centimeters below the surface. The scientists were looking for a signature of water in the craters near the poles, but found evidence for water instead on the sunlit portions of the moon. This was certainly unexpected and the science team from M3 looked and re-looked at their data for several months.

Confirmation came from a recent flyby of the re-purposed Deep Impact probe, on its way to rendezvous with another comet in 2010. In June of 2009, the spectrometer on board also showed strong evidence that water is ubiquitous over the surface of the moon.

Jessica Sunshine and colleagues with Deep Impact also found the presence of bound water or hydroxyl in trace amounts over much of the Moon’s surface. Their results suggest that the formation and retention of these molecules is an ongoing process on the lunar surface – and that solar wind could be responsible for forming them.

Still another spacecraft, the Cassini spacecraft while on its way to Saturn, also flew by the Moon in 1999. Roger Clark, a U.S. Geological Survey spectroscopist on the M3 team, reanalyzed archival data from Cassini, and that data as well agreed with the finding that water appears to be widespread across the lunar surface.

There are potentially two types of water on the moon: exogenic, meaning water from outside sources, such as comets striking the moon’s surface, and endogenic, meaning water that originates on the moon. The M3 research team, which includes Larry Taylor of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, suspect that the water they’re seeing in the moon’s surface is endogenic.

But where did the water come from?

The team from M3 believe it may come from the solar wind.

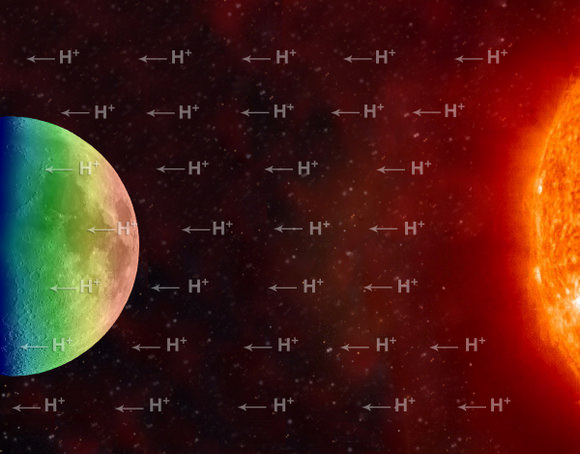

As the sun undergoes nuclear fusion, it constantly emits a stream of particles, mostly protons, which are positively charged hydrogen atoms. On Earth, the atmosphere and magnetism prevent us from being bombarded by these protons, but the moon lacks that protection, meaning the oxygen-rich minerals and glasses on the surface of the moon are constantly pounded by hydrogen in the form of protons, moving at velocities of one-third the speed of light.

When those protons hit the lunar surface with enough force, suspects Taylor, they break apart oxygen bonds in soil materials, and where free oxygen and hydrogen are together, there’s a high chance that trace amounts of water will be formed. These traces are thought to be about a quart of water per ton of soil.

“The isotopes of oxygen that exist on the moon are the same as those that exist on Earth, so it was difficult if not impossible to tell the difference between water from the moon and water from Earth,” said Taylor. “Since the early soil samples only had trace amounts of water, it was easy to make the mistake of attributing it to contamination.”

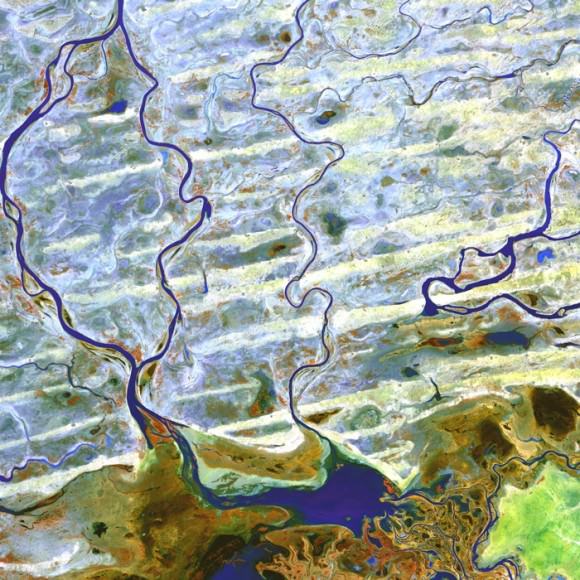

Lead image caption: Schematic showing the stream of charged hydrogen ions carried from the Sun by the solar wind. One possible scenario to explain hydration of the lunar surface is that during the daytime, when the Moon is exposed to the solar wind, hydrogen ions liberate oxygen from lunar minerals to form OH and H2O, which are then weakly held to the surface. At high temperatures (red-yellow) more molecules are released than adsorbed. When the temperature decreases (green-blue) OH and H2O accumulate. Image courtesy of University of Maryland/F. Merlin/McREL

Source: Science