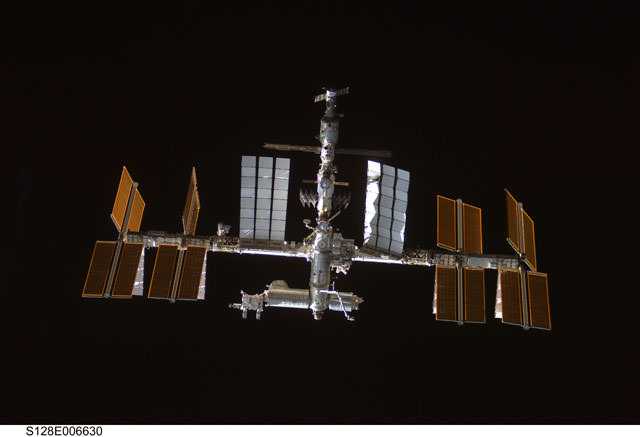

In their preliminary report, a panel of independent space experts commissioned by President Obama concluded that any human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit is not viable with the money NASA is expected to receive under the budget for 2010 and beyond. The Augustine Commission proposed several different options for NASA’s future path, which highlighted working closely with other countries and commercial spaceflight companies, as well as extending the life of the space shuttle through 2011. But NASA is on an “unsustainable trajectory,” and going to the Moon or Mars is not possible on the current level of funding, the Commission said. The only way the US could conduct a “meaningful” human spaceflight program would be by adding at least $3 billion annually to NASA’s budget.

See the complete report here (pdf file) but here’s a summary:

“The nation is facing important decisions on the future of human spaceflight,” the Commision Report stated. ” Will we leave the close proximity of low-Earth orbit, where astronauts have circled since 1972, and explore the solar system, charting a path for the eventual expansion of human civilization into space? If so, how will we ensure that our exploration delivers the greatest benefit to the nation? Can we explore with reasonable assurances of human safety? And, can the nation marshal the resources to embark on the mission? Whatever space program is ultimately selected, it must be matched with the resources needed for its execution.”

The Augustine Commision developed five alternatives for the Human Spaceflight Program, including a “Moon First” option or a “Flexible Path.” They said that funding at an increased level of $3 billion additional each year would allow for either plan.

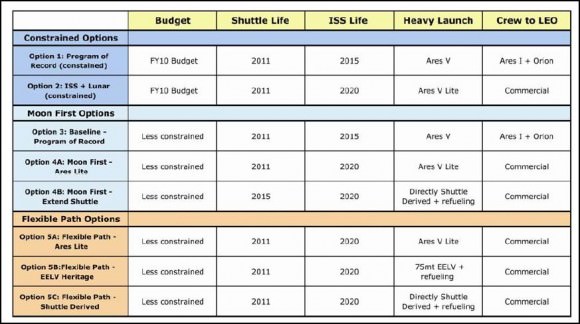

Here’s a graph of the options:

Option 1 is to continue with the current funding and the plan of building the Constellation Program. But the shuttle should be kept going until 2011 and then this would mean de-orbiting the ISS in 2016. With the proposed budget, Ares I and Orion are not available until after the ISS has been de-orbited. The heavy-lift vehicle, Ares V, wouldn’t be available until the late 2020s, and worse, funds would be insufficient funds to develop the lunar lander and lunar surface systems until well into the 2030s, if ever.

Option 2 again maintains the current budget. This option extends the ISS to 2020, and it begins a program of lunar exploration using a Lite version of Ares V. The option assumes the shuttles until FY 2011, and it includes a technology development program, a program to develop commercial crew services to low-Earth orbit, and funds for enhanced utilization of ISS. Heavy lift capabilities wouldn’t be developed until late 2020s and going to the Moon is not an option.

The remaining three alternatives employ the budget of an additional $3 billion for FY 2010, which then grows with inflation at a more reasonable 2.4 percent per year.

Option 3 would be keeping the current plan going. De-orbit the ISS in 2016, developing Orion, Ares I and Ares V, and beginning exploration of the Moon. But the shuttle should fly until 2011. The Committee concluded that Ares1/Orion would be available by 2017, with human lunar return in the mid-2020s.

Option 4 would send humans to the go the Moon first. It also extends the ISS to 2020, funds technology advancement, and uses commercial vehicles to carry crew to low-Earth orbit. There are two significantly different variations to this option.

Variant 4A is the Ares Lite variant. This retires the Shuttle in FY 2011 and develops the Ares V (Lite) heavy-lift launcher for lunar exploration. Variant 4B is the Shuttle extension variant. This variant includes the only foreseeable way to eliminate the gap in U.S. human-launch capability: it extends the Shuttle to 2015 at a minimum safe-flight rate. It also takes advantage of synergy with the Shuttle by developing a heavy-lift vehicle that is more directly Shuttle-derived. Both variants of Option 4 permit human lunar return by the mid-2020s.

Option 5. Flexible Path. This option follows the Flexible Path as an exploration strategy. It operates the Shuttle into FY 2011, extends the ISS until 2020, funds technology development and develops commercial crew services to low-Earth orbit. There are three variants within this option; they differ only in the heavy-lift vehicle.

Variant 5A is the Ares Lite variant. It develops the Ares Lite, the most capable of the heavylift vehicles in this option. Variant 5B employs an EELV-heritage commercial heavy-lift launcher and assumes a different (and significantly reduced) role for NASA. It has an advantage of potentially lower operational costs, but requires significant restructuring of NASA. Variant 5C uses a directly Shuttle-derived, heavy-lift vehicle, taking maximum advantage of existing infrastructure, facilities and production capabilities.

All variants of Option 5 begin exploration along the flexible path in the early 2020s, with lunar fly-bys, visits to Lagrange points and near-Earth objects and Mars fly-bys occurring at a rate of about one major event per year, and possible rendezvous with Mars’s moons or human lunar return by the mid to late 2020s.