Attendees at the AirVenture air show in Oshkosh, Wisconsin were treated with watching Virgin Galactic’s WhiteKnightTwo take flight. On board the mothership — which will launch space tourism and science customers into space — was none other than Vigin’s founder Richard Branson. “This was one of the most incredible experiences of my life,” Branson said after the flight. “It’s a beautiful aircraft to fly and its incredibly light carbon construction and efficient design points the way to a much brighter future for commercial aviation as well as the industrial revolution in space which I believe our entire space launch system heralds.”

Continue reading “Watch WhiteKnightTwo Take Flight (Video)”

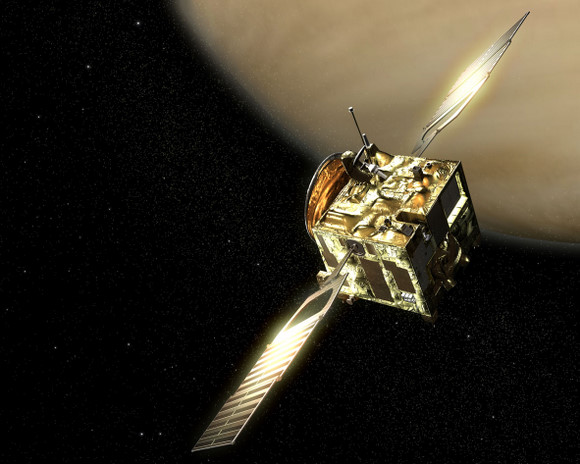

Climate of Venus

[/caption]

In many ways Venus is Earth’s twin planet. It’s only a little smaller, and made up of the same composition as Earth. But when it comes to climate, Venus couldn’t really be more different. Venus is a hellish world – the hottest planet in the Solar System, with an average temperature of more than 400°C, and a surface pressure almost 100 times what we experience here on Earth. On top of that, there are clouds of sulfuric acid and other corrosive chemicals. Visiting Venus would be the worst vacation ever.

Before the 1960s, scientists thought that the climate of Venus might be similar to Earth. It has clouds, and here Earth, clouds mean rain, water, oceans and even life. But microwave observations of Venus showed that its surface must be incredibly hot, too hot for liquid water to exist. And spacecraft visiting the planet in the 1960s and 70s confirmed that the clouds of Venus are made up almost entirely of carbon dioxide; a potent greenhouse gas keeping the planet so hot.

But you could say that Venus has a climate. It has severe winds that blow at speeds greater than 100 m/s; although, the winds don’t reach down to the surface of the planet. It has sulfuric acid clouds which send down torrents of sulfuric acid rain.

The climate of Venus wasn’t always this harsh. In fact, Venus used to have an atmosphere similar to our own. But at some point in Venus’ past, its global magnetosphere shut down. Without this global force field, the Sun’s solar wind was able to reach the planet and tear away at its atmosphere, stripping away the lighter atoms. The lightest atom is hydrogen, of course, one of the constituents of water. Recent observations by ESA’s Venus Express showed that this process is still going on today. 2 x 1024 atoms of hydrogen are being blasted off Venus into space every second.

We have written many articles about Venus for Universe Today. Here’s an article about Venus’ wet, volcanic past, and here’s an article about how Venus might have had continents and oceans in the ancient past.

Want more information on Venus? Here’s a link to Hubblesite’s News Releases about Venus, and here’s NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide to Venus.

We have recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast that’s only about planet Venus. Listen to it here, Episode 50: Venus.

Reference:

NASA: The Solar System

NASA: Pioneer Mission to Venus

Is There Water on Venus?

[/caption]

When astronomers first pointed their rudimentary telescopes at Venus, they saw a world shrouded in clouds. Here on Earth, clouds mean water, so early astronomers imagined a tropical world with constant rainfall. The truth, of course is that the thick atmosphere on Venus is made almost entirely of carbon dioxide. In fact, the atmospheric pressure on the surface of Venus is 92 times more than what you would experience on Earth. If the clouds are carbon dioxide, is there water on Venus.

Well, there isn’t any water on the surface of Venus, in form of rivers, lakes or oceans. The average temperature on Venus is 461.85 °C. Since water boils at 100 °C, it couldn’t be on the surface. But could water be in the clouds and atmosphere of Venus?

Astronomers have detected that the atmosphere of Venus consists of 0.002% water vapor. Compare that to the Earth’s atmosphere, which contains 0.40% water vapor.

Scientists think that Venus had a similar formation to Earth, and it was certainly bombarded by the same comets that delivered vast quantities of water to our early planet. So why has Venus lost its water, while Earth kept its water? Recent observations by ESA’s Venus Express spacecraft found that Venus has a trail of hydrogen and oxygen atoms blasted away from the planet by the Sun’s solar winds. Every second, there are 2 x 1024 hydrogen atoms streaming away from Venus. The Earth’s magnetosphere protects our atmosphere from the Sun, channeling the solar wind around the planet, and keeping it from reaching our atmosphere.

The Earth’s magnetosphere is generated by the convection of material deep inside the Earth. This happens because the large temperature difference between the outer core and the inner core. At some point, plate tectonics on Venus ceased, and the planet stopped releasing as much heat from the interior. Without a high temperature gradient, its inner convection stopped, taking away its planet-wide magnetosphere.

It’s estimated that Earth’s atmosphere and surface has 100,000 times as much water as Venus. And if we didn’t have our protective magnetosphere, we’d be losing our water too.

We have written many articles about Venus for Universe Today. Here’s an article about Venus’ wet, volcanic past, and here’s an article about how Venus might have had continents and oceans in the ancient past.

Want more information on Venus? Here’s a link to Hubblesite’s News Releases about Venus, and here’s NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide to Venus.

We have recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast that’s only about planet Venus. Listen to it here, Episode 50: Venus.

Reference:

NASA Ask an Astrophysicist: Water on Venus

How Long Does it Take to Get to Venus?

[/caption]

Although humans have never made the voyage, spacecraft from Earth have visited Venus. So, how long does it take to get to Venus from Earth?

The first spacecraft ever launched towards Venus was the Soviet Venera 1 spacecraft. It was launched on February 12, 1961 on course to Venus. Unfortunately, scientists lost contact with the spacecraft on February 17th. Mission controllers didn’t get a chance to put in a course correction that would have directed it closer to Venus, so it’s thought to have passed within 100,000 km of the planet on May 19th. That’s a total time of 97 days; just over 3 months.

The first successful Venus flyby was NASA’s Mariner 2. This spacecraft was launched on August 8th, 1962 and made a successful flyby on December 14, 1962. So that calculates to 110 days from launch to arrival at Venus.

The most recent spacecraft to fly to Venus was ESA’s Venus Express. It was launched on November 9th, 2005, and took 153 days to make the journey to Venus.

Why is there such a big difference in travel times to Venus? It all comes down to the launch speed and trajectory. Both Earth and Venus are traveling on orbits around the Sun. You don’t just point your spacecraft directly at Venus and fire your rockets. You have to travel on a transfer orbit that moves you between Earth’s orbit and Venus’ orbit, catching up with Venus, ideally going into orbit. To make the trip with a smaller, less expensive rocket, you have to make a longer trip, taking more time.

Humans have never made the trip to Venus, but maybe someday they will; although, the planet would be extremely unpleasant to try and land on. Maybe just a flyby would be nice.

We have written many articles about Venus for Universe Today. Here’s an article about Venus’ wet, volcanic past, and here’s an article about how Venus might have had continents and oceans in the ancient past.

Want more information on Venus? Here’s a link to Hubblesite’s News Releases about Venus, and here’s NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide to Venus.

We have recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast that’s only about planet Venus. Listen to it here, Episode 50: Venus.

Keep Track of NEOs with New “Asteroid Watch” Website

With the recent impact on Jupiter, a lot of people out there have asteroids on their mind and wonder if one could possibly hit Earth. Now, NASA and JPL have a new website called “Asteroid Watch” which will keep everyone updated if any object approaches Earth. They’ve also created an Asteroid Watch Twitter account that Tweet updates on NEOs, plus there’s a downloadable widget as well.

“The goal of our Web site is to provide the public with the most up-to-date and accurate information on these intriguing objects,” said Don Yeomans, manager of NASA’s Near-Earth Object Program Office at JPL.

“This innovative new Web application gives the public an unprecedented look at what’s going on in near-Earth space,” said Lindley Johnson, program executive for the Near-Earth Objects Observation program at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

Information is garnered from surveys and missions that detect and track asteroids and comets passing close to Earth. The Near-Earth Object Observation Program, commonly called “Spaceguard,” also plots the orbits of these objects to determine if any could be potentially hazardous to our planet.

There’s also another non-NASA Twitter feed called lowflyingrocks that lets you know about every Near Earth Object that passes within 0.2AU of Earth.

Source: JPL

Observe the Jupiter Impact Site!

[/caption]

Have you stayed up late and observed the Jupiter impact site? Then don’t be goofing around. Not since July 16-22, 1994 when comet Shoemaker-Levy crashed into Jupiter’s southern hemisphere have amateur astronomers had the opportunity to witness history firsthand! What makes me think that you can do it? Because I have…

Not only have cameras been clicking around the world, but they’ve been rolling, too.. Let’s take a look at one from John Chumack!

These images were done from his backyard Observatory in Dayton, Ohio USA, using A DMK 21F04 Fire-wire Camera and 2x Barlow, Optec Filter Wheel, attached to a Meade 10″ SCT scope. Captured images starting about 2:00 am and ran until 4:30 am E.ST. on 07-28-09. Basically 2.5 hours of rotation compressed to about 10 seconds. Way to go, John!!

If you think you have to be a professional, then think again. Even with less than perfect sky conditions, the impact site is very noticeable in a telescope as small as 4.5″ on a swimmy horizon and just gets better and easier to see as it reaches meridian and Jupiter reaches better sky position. DO NOT wait on the perfect night and the perfect time – because it just might not happen.

Another reason for my observations was to see just how close my predictions were… and without using a computer program? Hey… The old girl still has got it. Get thee out there on these Universal dates and times! July 29, 4:14, 14:20 and 23:59; July 30, 10:01 and 19:56; July 31, 5:52 and 15:48. For August 1, 01:43, 11:39, 21:34; August 2, 7:32 and 17:25; August 3, 3:23, 13:17 and 23:12; August 4, 9:08 and 19:03; August 5, 4:59 and 14:54; August 6, 0:50, 10:46 and 20:41; August 7, 6:37 and 16:32; August 8, 2:28, 12:24 and 22:18; August 9, 8:15 and 18:20; August 10, 4:06, 14:01, 23:57; August 11, 9:53 and 19:48; August 12, 5:42 and 15:39; August 13, 01:35, 11:31 and 21:26; August 14, 7:22 and 17:17; August 15, 3:13, 13:08, 23:04. I might be off by a few minutes, but I’m not that far off.

Take your time and do not just glance at Jupiter and think it’s not there at the predicted time – because it is. The charcoal gray oval is big enough and dark enough to stand out against the wash of the southern hemisphere, but sometimes you have to wait on a moment of clarity to see it. Try using a variety of color filters, but instead of installing them in the eyepiece, use the “blink” method. Hold the filter by the cell and simply set it on the eyepiece while you look through it, then take it off and look again. Once you see the mushroom cloud, you can’t “un-see” it.

History is waiting on you… Carpe noctem, baby!

Many, many thanks to John Chumack of Galactic Images for sharing this wonderful capture of what I was looking at last night and allowing me to adjust his original image to highlight the impact region!

Weight on Venus

[/caption]

Want to lose some weight? Travel to Venus and you’ll feel lighter right away. Well, the high temperatures, intense pressures, and corrosive chemicals will make the experience unpleasant (and kill you instantly), but you’ll definitely be lighter on the scales. So what would your weight be on Venus?

The force of gravity on the surface of Venus is 90% the force of gravity you experience on Earth. In other words, if your bathroom scale reads 100 kg, it would only read 90 kg on Venus. For you imperial folks, if you weighed 150 pounds on Earth, you would weigh 135 pounds on Venus.

If Earth and Venus are considered twin planets, why wouldn’t you weigh the same? Well, Venus and Earth are very similar, but they’re not actually twin planets. Venus is only 95% the size of Earth, and 81% of its mass. With the smaller size and mass, the force of gravity pulling you on the surface is lower.

To get your weight on Venus, just multiply your current weight by 0.9. That’s why 100 pounds becomes 90 pounds. You can also do the reverse calculation and figure out how high you could jump, or what you could carry on Venus by dividing a number by 0.9. For example, the world record high jump is currently 2.45 meters. If that was done on Venus, it would be 2.72 meters (2.45 / 0.9).

Just one last thing. It’s important to note that kilograms are a measure of mass; how much stuff an object has. Your mass doesn’t change when you travel from planet to planet, or anywhere in the Universe. It would be more accurate to measure your weight in newtons, but bathroom scales don’t have that option. That’s why we say that your weight in kilograms changes from planet to planet.

We have written many articles about Venus for Universe Today. Here’s an article about Venus’ wet, volcanic past, and here’s an article about how Venus might have had continents and oceans in the ancient past.

Want more information on Venus? Here’s a link to Hubblesite’s News Releases about Venus, and here’s NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide to Venus.

We have recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast that’s only about planet Venus. Listen to it here, Episode 50: Venus.

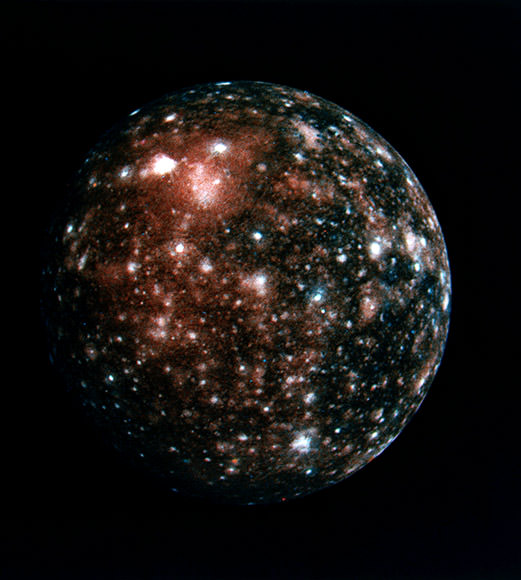

Where In The Universe #64

It’s time once again for another Where In The Universe Challenge. Test your visual knowledge of the cosmos by naming where in the Universe this image was taken and give yourself extra points if you can name the spacecraft responsible for this picture. Post your guesses in the comments section, and check back later at this same post to find the answer. To make this challenge fun for everyone, please don’t include links or extensive explanations with your answer. Good luck!

UPDATE: The answer has now been posted below.

This is a false color picture of Callisto, taken by Voyager 2 on July 7, 1979 from about 1,094,666 kilometers (677,000 miles) away. The surface of Callisto is the most heavily battered and cratered of the Jupiter’s moons and resembles ancient heavily cratered terrains on the Moon, Mercury and Mars. The bright areas are ejecta thrown out by relatively young impact craters. A large ringed structure, probably an impact basin, is shown in the upper left part of the picture.

How’d you do?

Check back next week for another WITU Challenge!

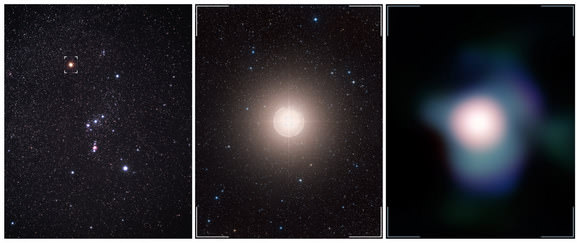

Closest-Ever Look At Betelgeuse Reveals its Fiery Secret

[/caption]

The giant star Betelgeuse churns out gas bubbles that match its own size — and that’s how it can shed an entire solar mass in 10,000 years.

That according to the sharpest-ever images of Orion’s second-brightest star, released this week by the European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO). At left is an artist’s impression of the supergiant star Betelgeuse as it was revealed in the new images (courtesy of ESO and L.Calçada). The actual images follow …

Betelgeuse, the second brightest star in the constellation of Orion (the Hunter), is a red supergiant, one of the biggest stars known, and almost 1,000 times larger than our Sun. It is also one of the most luminous stars known, emitting more light than 100,000 Suns.

Red supergiants still hold several unsolved mysteries. One of them is just how these behemoths shed such tremendous quantities of material — about the mass of the Sun — in only 10,000 years.

With an age of only a few million years, the Betelgeuse star is already nearing the end of its life and is soon doomed to explode as a supernova. When it does, the supernova should be seen easily from Earth, even in broad daylight.

Using ESO’s Very Large Telescope, two independent teams of astronomers have obtained the sharpest ever views of the supergiant star.

The first team used the adaptive optics instrument, NACO, combined with a so-called “lucky imaging” technique, to obtain the sharpest ever image of Betelgeuse, even with Earth’s turbulent, image-distorting atmosphere in the way. With lucky imaging, only the very sharpest exposures are chosen and then combined to form an image much sharper than a single, longer exposure would be.

The resulting NACO images almost reach the theoretical limit of sharpness attainable for an 8-metre telescope. The resolution is as fine as 37 milliarcseconds, which is roughly the size of a tennis ball on the International Space Station (ISS), as seen from the ground.

“Thanks to these outstanding images, we have detected a large plume of gas extending into space from the surface of Betelgeuse,” said Pierre Kervella from the Paris Observatory, who led the team. The plume extends to at least six times the diameter of the star, corresponding to the distance between the Sun and Neptune. “This is a clear indication that the whole outer shell of the star is not shedding matter evenly in all directions.”

Two mechanisms could explain this asymmetry. One assumes that the mass loss occurs above the polar caps of the giant star, possibly because of its rotation. The other possibility is that such a plume is generated above large-scale gas motions inside the star, known as convection — similar to the circulation of water heated in a pot.

To arrive at a solution, Keiichi Ohnaka from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany, and his colleagues used ESO’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer. The astronomers were able to detect details four times finer still than the NACO images had allowed — in other words, the size of a marble on the ISS, as seen from the ground.

“Our AMBER observations are the sharpest observations of any kind ever made of Betelgeuse. Moreover, we detected how the gas is moving in different areas of Betelgeuse’s surface — the first time this has been done for a star other than the Sun,” Ohnaka said.

The AMBER observations revealed that the gas in Betelgeuse’s atmosphere is moving vigorously up and down, and that these bubbles are as large as the supergiant star itself. The astronomers are proposing that these large-scale gas motions roiling under Betelgeuse’s red surface are behind the ejection of the massive plume into space.

Source: European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO). Two related papers are here and here.

Inside of Venus

From our perspective here on Earth, Venus is completely covered in clouds. So what’s inside Venus? For most of history, scientists had no idea what’s inside of Venus. The earliest telescopes showed hazy cloud tops, and even the largest telescopes didn’t improve the view. Some astronomers thought they might have caught a glimpse of the surface through the clouds, or maybe the peak of a tall mountain poking up through the clouds. But we now know those were just observation errors.

It wasn’t until the first spacecraft from Earth arrived at Venus, and started gathering scientific data about the inside of Venus. NASA’s Mariner 2 helped scientists calculate that the density of Venus is very similar to the density of Earth. Although there were no direct observations of Venus’ interior, scientists assume that it must be similar to Earth. The inside of Venus is thought to contain a solid/liquid core of metal 3,000 km across. This is surrounded by a mantle of rock 3,000 km thick. And then there’s a thin crust of rock about 50 km thick.

When NASA’s Magellan spacecraft was launched to Venus in 1989, it was carrying a suite of powerful radar mapping instruments. These tools could pierce through the thick clouds surrounding Venus and reveal the surface of the planet in great detail. Magellan found that the surface of Venus is actually quite young, and was probably resurfaced 300-500 million years ago, based on the number of impact craters found on its surface.

Magellan also found evidence of a large number of volcanoes; they number in the thousands and maybe even in the millions. The shield volcanoes found across the surface of Venus indicate that the inside of Venus is still active, with magma pushing to the surface around the planet.

It’s believed that the event that resurfaced Venus 300-500 million years ago might have also shut down plate tectonics on Venus. Without the movement of plates to release trapped heat, the inside of Venus remained much hotter than it would be. It’s thought that this increase in heat also shut down the convection of metal around the core of Venus. It’s this convection in the Earth’s core that’s thought to run our planet’s magnetic field.

We have written many articles about Venus for Universe Today. Here’s an article about Venus’ wet, volcanic past, and here’s an article about how Venus might have had continents and oceans in the ancient past.

Want more information on Venus? Here’s a link to Hubblesite’s News Releases about Venus, and here’s NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide to Venus.

We have recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast that’s only about planet Venus. Listen to it here, Episode 50: Venus.

References:

NASA Solar System Exploration: Terrestrial Planets

Venus Interior