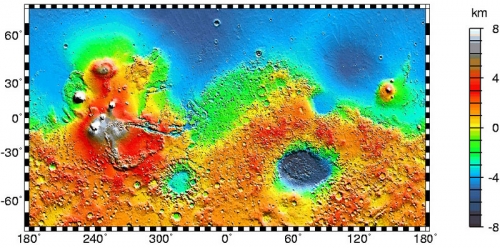

Mars has two faces. No, not those kind of faces, but the notable differences between the northern and southern hemisphere. Mars has lowlands in the north and highlands in the south. This disparity has long puzzled planetary scientists, but most concurred that early in Mars history, impacts shaped the planet’s two-faced landscape. But many disagreed whether several small impacts or one big one were responsible for sculpting Mars’ surface. Now scientists at the California Institute of Technology have shown through computer modeling that the Mars dichotomy, as the divided terrain has been termed, can indeed be explained by one giant impact early in the planet’s history.

“The dichotomy is arguably the oldest feature on Mars,” said Oded Aharonson from Caltech. Scientists believe the differences in hemispheric features arose more than four billion years ago.

Previously, scientists discounted the idea that a single, giant impactor created the lower elevations and thinner crust of Mars’s northern region, says Margarita Marinova, a graduate student at Caltech, and one of the lead authors of the study.

For one thing, Marinova explained, it was thought that a single impact would leave a circular footprint, but the outline of the northern lowlands region is elliptical. There is also a distinct lack of a crater rim: topography increases smoothly from the lowlands to the highlands without a lip of concentrated material in between, as is the case in small craters. Finally, it was believed that a giant impactor would obliterate the record of its own occurrence by melting a large fraction of the planet and forming a magma ocean.

“We set out to show that it’s possible to make a big hole without melting the majority of the surface of Mars,” Aharonson says. The team modeled a range of projectile parameters that could yield a cavity the size and ellipticity of the Mars lowlands without melting the whole planet or making a crater rim.

The team ran over 500 computer simulations combining various energies, velocities, and impact angles. Finally, they were able to narrow in on a “sweet spot”–a range of single-impact parameters that would make exactly the type of crater found on Mars. Their dedicated supercomputer allowed them to run simulations not run in the past. “The ability to search for parameters that allow an impact compatible with observations is enabled by the dedicated machine at Caltech,” Aharonson said.

The favored simulation conditions outlined by the sweet spot suggest an impact energy of around 1029 joules, which is equivalent to 100 billion gigatons of TNT. The impactor would have hit Mars at an angle between 30 and 60 degrees while traveling at 6 to 10 kilometers per second. By combining these factors, Marinova calculated that the projectile was roughly 1,600 to 2,700 kilometers across.

Estimates of the energy of the Mars impact place it squarely between the impact that is thought to have led to the extinction of dinosaurs on Earth 65 million years ago and the one believed to have extruded our planet’s moon four billion years ago.

Marinova said the timing of formation of our moon and the Mars dichotomy is not coincidental. “This size range of impacts only occurred early in solar system history,” she says. The results of this study are also applicable to understanding large impact events on other heavenly bodies, like the Aitken Basin on the moon and the Caloris Basin on Mercury.

This report, published in the June 26 issue of Nature, goes along with two other papers on the Mars dichotomy. One published by Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna and Maria Zuber of MIT and Bruce Banerdt of JPL examine the gravitational and topographic signature of the dichotomy with information from the Mars orbiters. Another accompanying report, from a group at UC Santa Cruz led by Francis Nimmo, explores the expected consequences of mega-impacts.

Original News Source: EurekAlert