Dear Phoenix lander,

As I write this you are still tucked safely inside your spacecraft, speeding towards your destination on Mars. The engineers watching over you during this journey tell us you are healthy, doing well, and are so zeroed in on your target that they may not need to adjust your trajectory. However, they’ll provide a gentle nudge to alter your course if they deem it necessary.

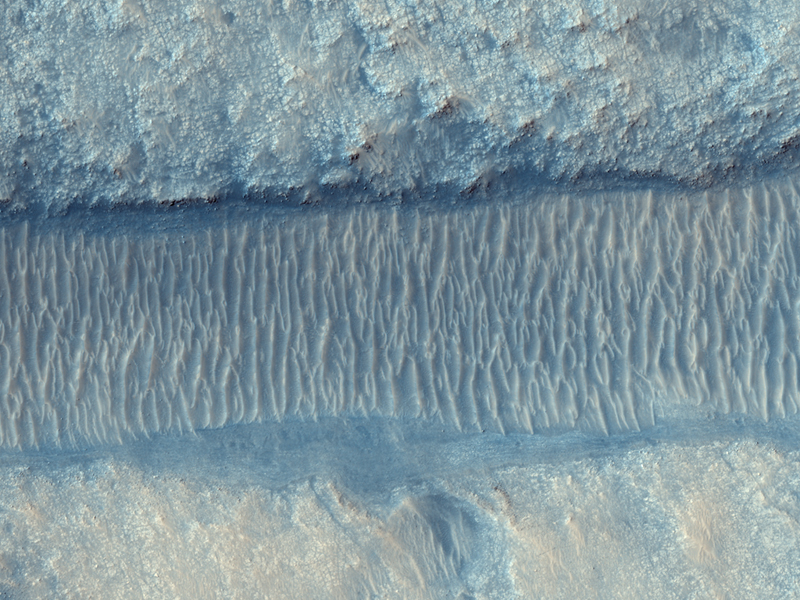

It looks like you’ll have good weather for your arrival, with no significant dust storms predicted at the northern polar region of Mars. It’s always nice to have good weather for a landing.

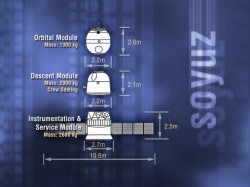

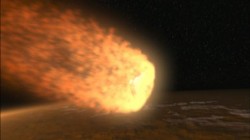

Just to let you know, when you reach the Red Planet, your descent through the atmosphere might be a little scary. In fact, people back on Earth are calling it “7 Minutes of Terror.” But, to be upfront with you, it’s actually closer to 8 minutes that you’ll have to slow from your incoming speed of about 21,000 kph (13,000 mph) to about 8 kph ( 5 mph) just before you touch down on the surface. I know, I know – you’re probably wondering why the Mars Rovers Spirit and Opportunity only had 6 minutes of terror to endure, and you have almost 8. You’re landing at a lower site on Mars surface, and so you’ll have a longer ride down.

But in fact, it might be scarier for all of us back on Earth who will be aching to know of your progress, than it will be for you. Your ablator heat shield will keep you room-temperature cool, even though the outside temperatures may reach 3,000 degrees Celsius.

You’ll also have a little longer ride on your parachute than the MER — 2 minutes versus 1 minute, although you won’t be traveling anywhere near a leisurely speed. And don’t worry about the parachute design. It’s the same type of parachute that was used for the Viking Landers back in the 1970’s and for MER. It’s tried and tested.

You have 12 thrusters to slow you down just before you land. May they serve you well.

But don’t worry about being alone during these 7-plus minutes. People from all around Earth will be watching and waiting to hear how your journey is progressing. More significantly, scientists and engineers from many different countries will be monitoring your journey with large telescopes and antennas from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory and the Deep Space Network, listening for the signals and tracking your progress, to keep an eye on how you’re doing.

However, to be honest with you, all of us back on Earth will only receive your transmissions 15 minutes after the fact of whatever occurs. But so many people have put a tremendous amount of time and effort into ensuring that your systems will perform flawlessly. We have great faith in their efforts and tremendous confidence in your capabilities.

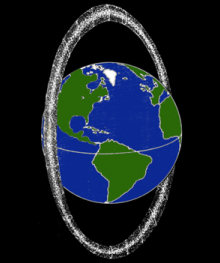

But you definitely won’t be alone because there are other spacecraft at Mars that will be ready to welcome you on your arrival, by scanning for your transmissions. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the Mars Odyssey and Mars Express, will all be searching for your signals, and MRO will even try to take a picture of you as you descend with your parachute.

You are undertaking a new adventure of exploration and discovery. We anticipate all that you will help us learn about Mars and its climate history by digging down through the arctic ice.

Please know we are all thinking of you and wishing you every success in your journey and subsequent scientific investigations.

Take care, Phoenix, and please call after you land to let us know if you’ve arrived safely.

All our hopes,

Your friends back on Earth

Real-time video of Phoenix’s descent and landing.