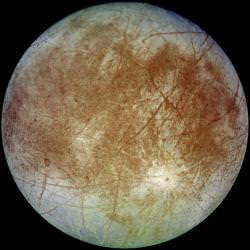

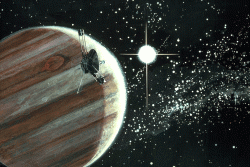

How do you determine the thickness of an ocean that you can’t see, let alone know how salty it is? Europa, the sixth satellite from Jupiter, is thought to have an ocean of liquid water underneath its icy surface. We know this because of its remarkably uncratered surface and the way its magnetic field reacts with that of Jupiter. New results that take into consideration Europa’s interaction with the plasma surrounding Jupiter – in addition to the magnetic field – give us a better picture of the ocean’s thickness and composition. This will help future robotic explorers know how deep they need to tunnel to reach the oceans underneath.

“We know from gravity measurements made by Galileo that Europa is a differentiated body. The most plausible models of Europa’s interior have an H2O-ice layer of thickness 80-170km. However, the gravity measurements tell us nothing about the state of this layer (solid or liquid),” said Dr. Nico Schilling of the Institut für Geophysik und Meteorologie in Köln, Germany.

The water in Europa’s ocean – just like the water in our own ocean – is a good conductor of electricity. When a conductor passes through a magnetic field, electricity is produced, and this electricity has an effect on the magnetic field itself. It’s just like what happens inside an electric generator. This process is called electromagnetic induction, and the intensity of the induction gives a lot of information about the materials involved in the process.

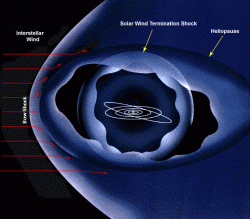

But Europa doesn’t only interact with the magnetic field coming from Jupiter, however; it also has electromagnetic interactions with the plasma surrounding Jupiter, called the magnetospheric plasma. This same thing happens on Earth in a way that is very familiar: Earth has a magnetosphere, and when plasma coming from the Sun interacts with our magnetosphere we see the beautiful Aurora Borealis phenomenon.

This process, happening intermittently as Europa orbits Jupiter, has an effect on the induction field of the subsurface ocean of the moon. By combining these measurements with the previous measurements of the interaction between Europa and Jupiter’s magnetic field, the researchers were able to get a better picture of just how thick and how conductive Europa’s ocean is. Their results were published in a paper titled, Time-varying interaction of Europa with the jovian magnetosphere: Constraints on the conductivity of Europa’s subsurface ocean, which appears in the August 2007 edition of the journal Icarus.

The researchers compared their models of Europa’s electromagnetic induction with the results of Galileo’s magnetic field measurements, and found that the total conductivity of the ocean was about 50,000 Siemens (a measure of electrical conductivity). This is much higher than previous results, which placed the conductivity at 15000 Siemens.

Depending on the composition of the ocean, though, the thickness could be between 25 and 100km, which is also thicker than the previously estimated lower limit of 5km. The less conductive the ocean is, the thicker it must be to account for the measured conductivity, and this depends on the quantity and type of salt found in the ocean, which still remains unknown.

Taking into account the interactions with the magnetospheric plasma are important when studying the composition of planets and moons.

Dr. Schilling said, “The plasma interaction effects the magnetic field measurements, but not e.g. the gravity measurements. So in every case in the Jupiter system, where magnetic field measurements were used to get some informations from the interiors of the moons, the plasma interaction has to be considered. An example is for instance Io, where the first flybys suggested that Io may have an internal dynamo field. It turned out that the measured magnetic field perturbation was not an internal field but was created by the plasma interaction.”

Europa and Io, though, are not the only place where magnetic fields and plasma interactions can tell us about the nature of a planet’s interior; this same method was also used to detect the geysers of Enceladus, one of Saturn’s moons.

“The first hints of an active south polar region came from the magnetic field measurements and the simulations of the plasma interaction, before Cassini actually saw the geysers,” Dr. Schilling said.

With the discovery of entire ecosystems at the bottom of oceans here on Earth – ecosystems entirely cut off from sunlight – the discovery of oceans on Europa gives scientists hope that there could be life there. And this new discovery helps researchers understand what kind of ocean they could be dealing with.

Now, we just have to tunnel down through the shell of ice and look for ourselves.

Source: Icarus