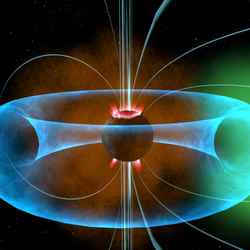

Artist’s impression of Earth auroras. Image credit: NASA Click to enlarge

Scientists from NASA and the National Science Foundation discovered a way to combine ground and space observations to create an unprecedented view of upper atmosphere disturbances during space storms.

Large, global-scale disturbances resemble weather cold fronts. They form in the Earth’s electrified upper atmosphere during space storms. The disturbances result from plumes of electrified plasma that form in the ionosphere. When the plasma plumes pass overhead, they impede low and high frequency radio communications and delay Global Positioning System navigation signals.

“Previously, they seemed like random events,” said John Foster, associate director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Haystack Observatory. He is principal investigator of the Foundation supported Millstone Hill Observatory, Wesford, Mass.

“People knew there was a space storm that must have disrupted their system, but they had no idea why,” said Tony Mannucci, group supervisor of Ionospheric and Atmospheric Remote Sensing at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “Now we know it’s not just chaos; there is cause and effect. We are beginning to put together the full picture, which will ultimately let us predict space storms.”

Predicting space weather is a primary goal of the National Space Weather Program involving NASA, the foundation and several other federal agencies. The view researchers created allowed them to link movement of the plumes to processes that release plasma into space. “Discovering this link is like discovering the movement of cold fronts is responsible for sudden thunderstorms,” said Jerry Goldstein, principal scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio.

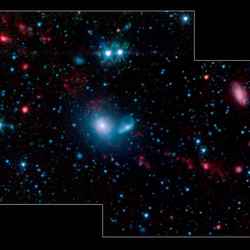

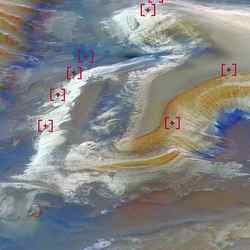

Since the occurrence of plasma plumes in the ionosphere disrupts GPS signals, they provide a continuous monitor of these disturbances. Researchers discovered a link between GPS data and satellite images of the plasmasphere. The plasmasphere is a plasma cloud surrounding Earth above the ionosphere. It is being observed from NASA’s Imager for Magnetopause to Aurora Global Exploration satellite. The researchers discovered the motion of the ionospheric plumes corresponded to the ejection of plasma from the plasmasphere during space storms.

The combined observations allowed construction of an underlying picture of the processes during space storms, when the Earth’s magnetic field is buffeted by hot plasma from the sun. As the solar plasma blows by, it generates an electric field that is transmitted to the plasmasphere and ionosphere. This electric field propels the ionospheric and the plasmaspheric plasma out into space. For the first time, scientists can directly connect the plasma observed in the ionosphere with the plasmasphere plumes that extend many thousand of kilometers into space.

“We also know these disturbances occur most often between noon and dusk, and between mid to high latitudes, due to the global structure of the electric and magnetic fields during space storms,” said Anthea Coster of the Haystack Observatory. “Ground and space based, and in situ measurements are allowing scientists to understand the ionosphere-thermosphere-magnetosphere as a coupled system.”

The plumes degrade GPS signals in two primary ways. First, they cause position error by time delaying the propagation of GPS signals. Second, the turbulence they generate causes receivers to lose the signal through an effect known as scintillation. It is similar to the apparent twinkling of stars caused by atmospheric turbulence.

Researchers are presenting the findings today during the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco, Calif. For information about space weather and other research on the Web, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/vision/universe/solarsystem/cold_front.html

Original Source: NASA News Release