Download our free “What’s Up 2006” ebook, with entries like this for every day of the year.

|

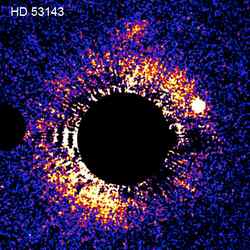

M44. Image credit: NOAO/AURA/NSF. Click to enlarge.

Monday, January 16 – Although the early rise of tonight’s Moon will hamper the Delta Cancrid meteor shower, be on the lookout for fast moving meteors appearing to radiate from an area just west of the “Beehive” – M44. It’s a minor shower, with a fall rate of about 4 per hour, but it’s fun to catch one!

While we’re watching, take a look at M44 with binoculars or a low power telescope. You’ll find it in the center of the triangle of bright stars, Pollux, Regulus, and Procyon, and it is usually visible to the unaided eye from dark sky locations. Better known as the “Beehive,” M44 shows several dozen stars through binoculars. Through the scope, the cluster reveals up to 100 stars! Of the 400 known members, most congregate in an elliptical “swarm” spanning 15 light-years. The “Beehive” is only slightly more distant than the Pleiades at 500 light-years away. Thanks to its advanced stellar evolution, it contains several red giants, leading astronomers to believe it is around 400 million years old.

After moonrise, have a look at the lunar surface as the terminator reaches the edge of Mare Crisium in the northeastern quarter. Depending on your viewing time, you may have the opportunity to spot small craters Alhazen and Hansen on its eastern edge. Look for a long “wrinkle” creasing Crisium’s smooth sands. Such lunar features are known as dorsae. Dorsa Tetyaev and Dorsa Harker come together along Mare Crisium’s eastern shore. Look for south-central Dorsa Termier and Dorsum Oppel along Crisium’s west bank. These frozen “waves” of lava are millions of years old.

Tuesday, January 17 – With time to spare before Moon rise tonight, let’s hunt down that “wascally wabbit” Lepus and have a look at M79. Let Alpha and Beta be your guide as you drop the same distance between them to the south for double star ADS3954 and this cool little globular cluster.

Discovered by Pierre M?chain in 1780, M79 is not large, nor bright, but is visible in binoculars. Large telescopes will find it well resolved with a rich core area. Around 50,000 light-years away, this particular globular is very low in variables and recedes from us at a “rabbit” speed of 118 miles per second. But, don’t worry – it will remain visible for a very long time!

Now, take a quick look at tonight’s Moon. The terminator has advanced through Mare Crisium and looks like a gigantic “bite” taken out of the lunar edge.

Wednesday, January 18 – If you are up before dawn, why not spend a moment looking at the sky? Although the Moon will still be bright, stay on watch for meteors belonging to the Coma Berenicid shower. The fall rate is very modest with only one or two per hour, but these are among the very fastest meteors known. Blazing through the atmosphere at 65 kilometers per second, the trails will point back to the Coma Berenices star cluster east of Leo.

Since we’ll have early dark skies, let’s have a look at a single star – R Leporis. Because it is variable, ranging in magnitude from 5.5 to 11.7, R may or may not be visible to the unaided eye tonight. Use a telescope, or binoculars, to locate it west of Mu. Look for a line of three dim stars and choose the centermost.

Most commonly known as “Hind’s Crimson Star,” this long term, pulsating red variable was discovered in 1845 by J.R. Hind. Its light changes by a factor of 250 times during its period of 432 days, but R Leporis can sometimes stall while brightening. As an old red star, R takes on a unique ruby-red color as it dims. To understand carbon stars, picture a kerosene lamp burning with its wick up high. This “high burn” causes the glass to smoke, dimming the light and changing the color. Although this example is simplistic, it hints at how carbon stars work. When it sloughs off the soot? It brightens again!

“Hind’s Crimson Star” is believed to be about 1500 light-years distant and moving slowing away from us at about 32 km per second. No matter how “bright” you find it tonight, its unusually deep red color makes it a true pleasure.

Thursday, January 19 – Johann Bode was born today in 1747. Bode publicized the Titus-Bode law, a nearly geometric progression of the distances of the planets from the Sun, and made a number of discoveries of deepsky studies objects. Also born today in 1851, was Jacobus Kapteyn. Kapteyn studied the distribution and motion of almost half a million stars and created the first modern model of the size and structure of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Tonight in celebration of them both, let’s have a first look at a pair of circumpolar galaxies known as “Bode’s Nebulae.” Discovered by Johann in 1774, the galaxies known as M81 and M82 were first described by him as “nebulous.” In Bode’s time, it was thought such patches were solar systems in formation, but by Kapteyn’s time in the late 1800’s, astronomers were beginning understand the mechanics of stellar motion in the Milky Way galaxy. While M81 and M82 are not in good sky position right now, you can still track them down in binoculars. Look for the bowl of the “Big Dipper” and draw an imaginary line from Phecda to Dubhe (the southeastern and northwestern stars) and extend it the same distance northwest. Fade ever so slightly toward Polaris and enjoy this bright pair of island universes sharing space in the night.

Friday, January 20 – Born this day in 1573 was Simon Mayr. Although Mayr’s name is not widely recognized, we know the names he has given to Jupiter’s satellites. During 1609 and 1610, Mayr was observing moons of Jupiter at about the same time as Galileo. Though discovery was credited to Galileo, Mayr was given the honor of naming them. If you’re up before dawn, look for Jupiter in the constellation Libra and see if you can spot Io, Ganymede, Callisto and Europa for yourself!

Early dark skies mean a chance for serious study, and tonight our target will be a challenge. Head towards Zeta Ceti and neighboring Chi Ceti. When you’ve identified Chi, power up and look north-northwest to locate small, 11.8 magnitude galaxy NGC 681. It might be small and faint, but it’s a great example of barred spiral seen near edge-on. Mid-sized scopes will see little detail, but large instruments reveal a broad equatorial dust lane. At a distance of 55 million light-years, this peculiar galaxy is a rare sight. All its stars move at the same orbital speed around the core – hinting at vast quantities of unseen, mysterious “dark matter!”

Saturday, January 21 – John Couch Adams was born today in 1792. Adams, along with Urbain Le Verrier, mathematically predicted the existence of Neptune. Also born today in 1908 was Bengt Stromgren – developer of the theory of ionization nebulae (H II regions). Tonight we’ll take a look at an ionization nebula as we return for a more in-depth look at M42.

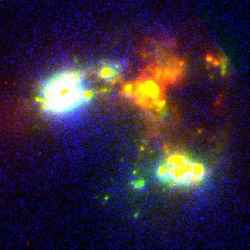

Known as “The Great Orion Nebula,” let’s learn what makes it glow. M42 is a great cloud of gas spanning more than 20,000 times the size of our own solar system and its light is mainly florescent. For most observers, it appears to have a slight greenish color – caused by oxygen being stripped of electrons by radiation from nearby stars. At the heart of this immense region is an area known as the “Trapezium” – its four brightest stars form perhaps the most celebrated multiple star system in the night sky. The Trapezium itself belongs to a faint cluster of stars now approaching main sequence and resides in an area of the nebula known as the “Huygenian Region” (named after 17th century astronomer and optician Christian Huygens who first observed it in detail).

Buried amidst the bright ribbons and curls of this cloud of predominately hydrogen gas are many star forming regions. Appearing like “knots,” these Herbig-Haro objects are thought to be stars in the earliest stages of condensation. Associated with these objects are a great number of faint red stars and erratically luminous variables – young stars, possibly of the T Tauri type. There are also “flare stars,” whose rapid variations in brightness mean an ever changing view.

While studying M42, you’ll note the apparent turbulence of the area – and with good reason. The “Great Nebula’s” many different regions move at varying speeds. The rate of expansion at the outer edges may be caused by radiation from the very youngest stars present. Although M42 may have been luminous for as long as 23,000 years, it is possible that new stars are still forming, while others were ejected by gravitation. Known as “runaway” stars, we’ll look at these strange members later in detail. A tremendous X-ray source (2U0525-06) is quite near the Trapezium and hints at the possibility of a black hole present within M42!

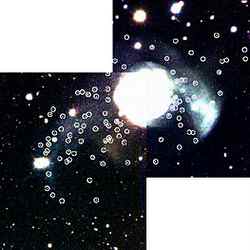

Sunday, January 22 – With tonight’s dark skies let’s have a look at another “cloud in space” – M78. It is easily located around two finger-widths north-northeast of Alnitak. Despite being 8th magnitude, you’ll probably need a telescope to see it. M78 is actually a bright outcropping of an extended region of nebulosity (the Orion Complex) including M42, 43, NGC 1975-77-79, the Flame Nebula, and the Horsehead. There’s plenty of material for future starbirth here! Nicknamed “Casper the Friendly Ghost Nebula,” M78 was discovered by Pierre Mechain in 1780. It shines almost purely by reflection and is the brightest non-emission nebula observable by amateurs. For larger scopes, look at nearby nebula NGC 2071. Unlike M78, NGC 2071 is associated with a single 10th magnitude star instead of the pair that gives “Casper” his glowing eyes.

Thank you again to all the kind folks who have responded to “365 Days of SkyWatching”! May all your journeys be at light speed… ~Tammy Plotner.